The rhodochrosite as crystal oscillator for being an alternative to those of quartz. The rhodochrosite (MnC03) shows complete solid solution with siderite (FeC03), and it may contain substantial amounts of Zn, Mg, Co, and Ca. Through an unrestricted Hartree-Fock (UHF) computational simulation, Compact effective potentials (CEP), the infrared spectrum of the protonated rhodochrosite crystal, CH19Mn6O8, and the load distribution by the unit molecule by two widely used methods, Atomic Polar Tensor (APT) and Mulliken, were studied. The rhodochrosite crystal unit cell of structure CMn6O8, where the load distribution by the molecule was verified in the UHF CEP-4G (Effective core potential (ECP) minimal basis), UHF CEP-31G (ECP split valance) and UHF CEP-121G (ECP triple-split basis). The largest load variation in the APT and Mulliken methods were obtained in the CEP-121G basis set, with δ = 2.922 e δ = 2.650 u.a., respectively, being δAPT > δMulliken. The maximum absorbance peaks in the CEP-4G, CEP-31G and CEP-121G basis set are present at the frequencies 2172.23 cm-1, with a normalized intensity of 0.65; 2231.4 cm-1 and 0.454; and 2177.24 cm-1 and 1.0, respectively. Later studies could check the advantages and disadvantages of rhodochrosite in the treatment of cancer through synchrotron radiation, such as one oscillator crystal.

rhodochrosite, quartz crystal, hartree-fock methods, apt, mulliken, effective core potential

The rhodochrosite as crystal oscillator for being an alternative to those of quartz. The rhodochrosite (MnC03) shows complete solid solution with siderite (FeC03), and it may contain substantial amounts of Zn, Mg, Co, and Ca. The electric charge that accumulates in certain solid materials, such as crystals, certain ceramics, and biological matter such as bone, DNA and various proteins in response to applied mechanical stress, phenomenon called piezoelectricity [1].

Through an unrestricted Hartree-Fock (UHF) computational simulation, Compact effective potentials (CEP), the infrared spectrum of the protonated rhodochrosite crystal, CH19Mn6O8, and the load distribution by the unit molecule by two widely used methods, Atomic Polar Tensor (APT) and Mulliken, were studied. The rhodochrosite crystal unit cell of structure CMn6O8, where the load distribution by the molecule was verified in the UHF CEP-4G (Effective core potential (ECP) minimal basis), UHF CEP-31G (ECP split valance) and UHF CEP-121G (ECP triple-split basis).

The electronic oscillator circuit that uses the mechanical resonance of a vibrating crystal of piezoelectric material to create an electrical signal with a precise frequency is a crystal oscillator. The most common type of piezoelectric resonator used is the quartz crystal, so oscillator circuits incorporating them became known as crystal oscillators [2]. Quartz crystals are manufactured for frequencies from a few tens of kilohertz to hundreds of megahertz. More than two billion crystals are manufactured annually. Most are used for consumer devices such as wristwatches, clocks, radios, computers, cellphones, signal generators and oscilloscopes [3-12].

But other crystals such as rhodochrosite also have piezoelectric properties. The rhodochrosite as crystal oscillator for being an alternative to those of quartz. The rhodochrosite (MnC03) shows complete solid solution with siderite (FeC03), and it may contain substantial amounts of Zn, Mg, Co, and Ca. The Kutnohorite [CaMn(C03)2] is a dolomite group mineral intermediary between rhodochrosite and calcite [3-12].

The Figure 1 is one photography the Rhodochrosite stone from China.

Figure 1. Rhodochrosite stone from China [13]

Hartree-Fock Methods

The Hartree-Fock self–consistent method [14-20] is based on the one-electron approximation in which the motion of each electron in the effective field of all the other electrons is governed by a one-particle Schrodinger¨ equation. The Hartree-Fock approximation takes into account of the correlation arising due to the electrons of the same spin, however, the motion of the electrons of the opposite spin remains uncorrelated in this approximation. The methods beyond self-consistent field methods, which treat the phenomenon associated with the many-electron system properly, are known as the electron correlation methods.

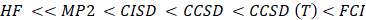

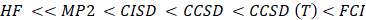

The vast literature associated with these methods suggests that the following is a plausible hierarchy:

The extremes of ‘best’, FCI, and ‘worst’, HF, are irrefutable, but the intermediate methods are less clear and depend on the type of chemical problem being addressed. [14] The use of HF in the case of FCI was due to the computational cost.

The molecular Hartree-Fock wave function is written as an antisymmetrized product (Slater determinant) of spin-orbitals, each spin-orbital being a product of a spatial orbital and a spin function (either

and a spin function (either  or

or  ).

).

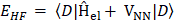

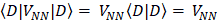

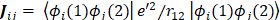

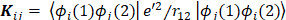

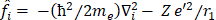

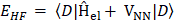

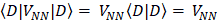

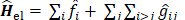

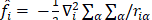

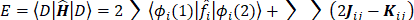

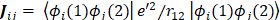

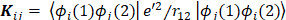

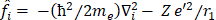

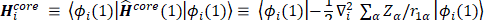

The expression for the Hartree-Fock molecular electronic energy  is given by the variation theorem as

is given by the variation theorem as  where D is the Slater-determinant Hartree-Fock wave function and

where D is the Slater-determinant Hartree-Fock wave function and  and

and  are given by

are given by

Since  does not involve electronic coordinates and D is normalized, we have

does not involve electronic coordinates and D is normalized, we have  . The operator

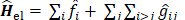

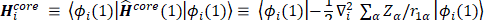

. The operator  is the sum of one-electron operators

is the sum of one-electron operators  and two-electron operators

and two-electron operators  ; we have

; we have  , where

, where  and

and  . The Hamiltonian

. The Hamiltonian  is the same as the Hamiltonian

is the same as the Hamiltonian  for an atom except that

for an atom except that  replaces

replaces  in

in  . Hence

. Hence

where

and

can be used to give  .

.

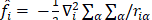

Therefore, the Hartree-Fock energy of a diatomic or polyatomic molecule with only closed shells is

and

where the one-electron-operator symbol was changed from  to

to  . [5]

. [5]

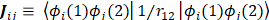

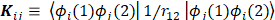

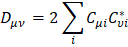

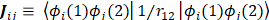

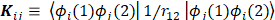

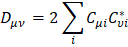

Mulliken Load

Mulliken's loads are derived from the Mulliken population analysis and provide means for estimating partial atomic charges from numerical chemistry calculations, particularly those based on the linear combination of atomic orbitals. If the coefficients of the basic functions in the molecular orbital are Cμi for μe the basic function ie in the orbital molecular, the coefficients of the density matrix are:

for a compact closed system in which each molecular orbital is doubly occupied. The population matrix P therefore has the following coefficients:

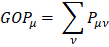

S is the overlay matrix for basic functions. The sum of the set of terms of  is N - the total number of electrons. The Mulliken population analysis aims first of all to distribute the N electrons on all the basic functions. This is done by taking the diagonal elements of

is N - the total number of electrons. The Mulliken population analysis aims first of all to distribute the N electrons on all the basic functions. This is done by taking the diagonal elements of  and factorizing the non-diagonal elements equally between the two appropriate basic functions. Non-diagonal terms including

and factorizing the non-diagonal elements equally between the two appropriate basic functions. Non-diagonal terms including  and

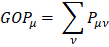

and  this simplifies the operation to a sum on a line. This defines the gross orbital population (GOB) as:

this simplifies the operation to a sum on a line. This defines the gross orbital population (GOB) as:

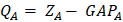

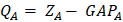

The terms  lie on N and then divide the total number of electrons between the basic functions. It then remains to sum these terms on all the basic functions of a given atom A in order to obtain the gross atomic population (GAP). The integral of the GAPA terms also gives N. The load, QA, is then defined as the difference between the number of electrons on the free isolated atom, which is the atomic number ZA, and the raw atomic population:

lie on N and then divide the total number of electrons between the basic functions. It then remains to sum these terms on all the basic functions of a given atom A in order to obtain the gross atomic population (GAP). The integral of the GAPA terms also gives N. The load, QA, is then defined as the difference between the number of electrons on the free isolated atom, which is the atomic number ZA, and the raw atomic population:

The problem with this approach is the even distribution of non-diagonal terms between the two basic functions. This leads to charge separations between the molecules that are exaggerated. Many other methods are used to determine atomic charges in molecules [21, 22].

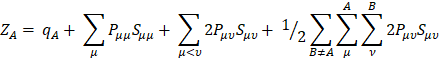

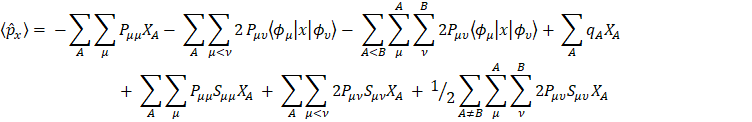

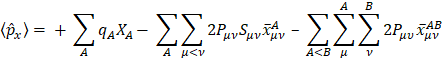

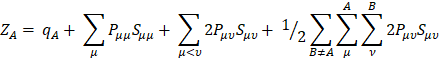

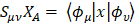

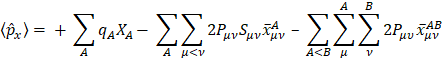

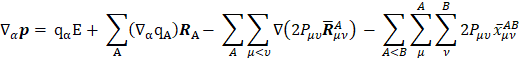

Concerning the nuclear contribution, the nuclear charge ZA can be written as ZA = qA + QA, where qA and QA account for the Mulliken net and gross atomic charge [21]. According to the Mulliken population analysis, the nuclear charge for A can be written as

which upon substitution in the dipole moment expression yields

Note that  and

and  so that

so that

where

and

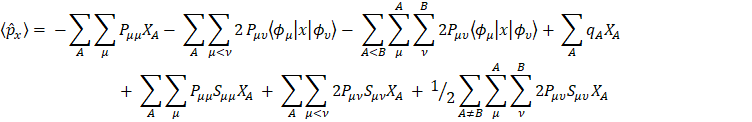

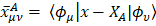

The first two terms in eq. for  are of atomic origin where the first one, involving the net atomic charge, is the only term with a classical counterpart. The second term resembles Coulson’s atomic dipole, and the integral

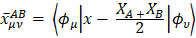

are of atomic origin where the first one, involving the net atomic charge, is the only term with a classical counterpart. The second term resembles Coulson’s atomic dipole, and the integral  is the distance from the centroid of the hybrid orbital to nucleus A. For the third term, the integral

is the distance from the centroid of the hybrid orbital to nucleus A. For the third term, the integral  is the distance of the center of charge from the midpoint of the chemical bond A-B. This contribution to the dipole moment has been referred to as the homopolar dipole [21] by Mulliken. As can be seen, the dipole moment has been partitioned into three contributions: the net atomic charge, the atomic dipole, and the homopolar dipole. Since the density matrix is invariant with respect to the choice of origin and since the sum of all net atomic charges vanishes, this partitioning of the dipole moment does not depend on the choice of origin for the system [5,23].

is the distance of the center of charge from the midpoint of the chemical bond A-B. This contribution to the dipole moment has been referred to as the homopolar dipole [21] by Mulliken. As can be seen, the dipole moment has been partitioned into three contributions: the net atomic charge, the atomic dipole, and the homopolar dipole. Since the density matrix is invariant with respect to the choice of origin and since the sum of all net atomic charges vanishes, this partitioning of the dipole moment does not depend on the choice of origin for the system [5,23].

Atomic Polar Tensor (APT)

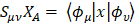

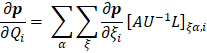

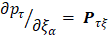

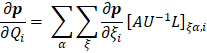

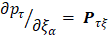

One of the most useful methods for interpreting and predicting infrared intensities comes from the atomic polar tensor (APT) formalism [24,25]. In the APT framework, the derivative of the molecular dipole moment vector with respect to the ith normal coordinate (which is directly related to the infrared intensity of the ith fundamental mode), can be expressed as

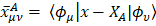

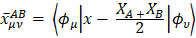

For each atom  in molecule, the quantities

in molecule, the quantities  where

where  and

and  form the APT, represent by a

form the APT, represent by a  matrix

matrix

So, if all the experimental infrared intensities and normal coordinates are known as well as the permanent dipole moment for a given molecule, the APT can be determined. On the other hand, these APTs can also be calculated by the SCF method and used to predict infrared intensities. These intensities can then be interpreted by partitioning the APT. This has been done before in the "charge-charge flux-overlap" (CCFO) model, first introduced by King and Mast [26,27] and later applied by Person et al. [28]

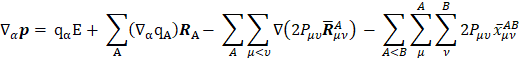

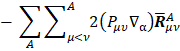

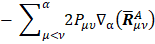

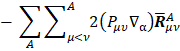

The general expression for the APT is:

where E is the identity matrix and each term of the APT is represented by a 3 X 3 matrix. The four contributions in the above equation can be identified according to Person, Coulson, and Mulliken terminology as charge, charge flux, atomic dipole flux, and homopolar dipole flux. Comparing with the CCFO model, the difference introduced in this work lies in the fact that the overlap term has been decomposed into two flux contributions (atomic dipole and homopolar dipole fluxes).

In eq. for  , the first two terms are the only classical contributions, one of them being the Mulliken net charge of atom a in its equilibrium position,

, the first two terms are the only classical contributions, one of them being the Mulliken net charge of atom a in its equilibrium position,  , and the other being the "charge flux" corresponding to charge migration as the chemical bond involving the

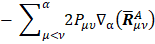

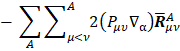

, and the other being the "charge flux" corresponding to charge migration as the chemical bond involving the  atom has been distorted. The sum over all atoms, A, implies there is electronic density deformation involving all the atoms in the molecule. These two terms have already been well discussed by Person, Zilles, and other [28-30]. The atomic dipole flux can be separated into two parts if the gradient of the density matrix and center of charge integrals are taken inside the parentheses:

atom has been distorted. The sum over all atoms, A, implies there is electronic density deformation involving all the atoms in the molecule. These two terms have already been well discussed by Person, Zilles, and other [28-30]. The atomic dipole flux can be separated into two parts if the gradient of the density matrix and center of charge integrals are taken inside the parentheses:

and

the first of the two terms in equation

involves only the atom for which the APT is being calculated because only these  depend on

depend on  .

.

Hardware and Software

For calculations a computer models were used: Intel CoreTM i3-3220 CPU @ 3.3 GHz x 4 processors [31], Memory DDR3 4 GB, HD SATA WDC WD7500 AZEK-00RKKA0 750.1 GB and DVD-RAM SATA GH24NS9 ATAPI, Graphics Intel Ivy Bridge [32].

For calculations of computational dynamics, the Ubuntu Linux version 16.10 system was used [33] and the software used for the molecular dynamics was GAMESS [16,34].

The Figure 2 show on cell structure of a protonated rhodochrosite crystal of structure Stoichiometric is CH19Mn6O8, obtained after molecular dynamics via unrestricted Hartree-Fock method, in basis set CEP-4G, CEP-31G and CEP-121G [35-96].

Figure 2. Cell structure of a protonated rhodochrosite crystal. Represented in red the oxygen; silver in color Manganese; in gray color Hydrogen; in light see green color the Carbon. Stoichiometry: CMn6O8. Stoichiometry protonated: CH19Mn6O8

The Figures 3 (A-D) show the normalized absorption spectrum as a function of the vibrational frequencies of the protonated rhodochrosite crystal for UHF-CEP-4G basis set, UHF-CEP-31G and UHF-CEP-121G.

Figure 3A. Absorbance spectrum plot as a function of vibrational frequencies of protonated rhodochrosite crystal for UHF-CEP-4G basis set

Figure 3B. Absorbance spectrum plot as a function of vibrational frequencies of protonated rhodochrosite crystal for UHF-CEP-31G basis set

Figure 3C. Absorbance spectrum plot as a function of vibrational frequencies of protonated rhodochrosite crystal for UHF-CEP-121G basis set

Figure 3D. Absorbance spectrum plot as a function of vibrational frequencies of protonated rhodochrosite crystal for UHF-CEP-4G basis set, UHF-CEP-31G and UHF-CEP-121G

The rhodochrosite crystal unit cell of structure CMn6O8, where the load distribution by the molecule was verified in the unrestricted Hartree-Fock method, UHF CEP-4G (Effective core potential (ECP) minimal basis), UHF CEP-31G (ECP split valance) and UHF CEP-121G (ECP triple-split basis), through the analysis of APT and Mulliken loads [97-103].

The rhodochrosite unit cell was protonated, then presented the structure CH19Mn6O8 for the study with ab initio methods with +4 multiplicity. The displacement of charges by the molecule was analyzed to verify the site of molecular action.

The load distribution by the protonated crystal is evaluated in Table (1), and its vibrational frequencies in Table 2.

Table 1. Load shifting on given basis sets of the Mulliken and APT method

Basis Sets |

Mulliken |

APT |

|

Charge* |

δ |

Charge* |

δ |

CEP-4G |

-1.064 |

+1.064 |

2.128 |

-1.366 |

+1.366 |

2.732 |

CEP-31G |

-1.034 |

+1.034 |

2.068 |

-1.362 |

+1.362 |

2.724 |

CEP-121G |

-1.325 |

+1.325 |

2.650 |

-1.461 |

+1.461 |

2.922 |

*±1,602 176 634 × 10−19 C (Coulomb)

Table 2. Peaks maximum absorption intensity by the frequency given. Absorbance frequency as a function of vibrational frequencies of protonated rhodochrosite crystal for UHF-CEP-4G basis set, UHF-CEP-31G and UHF-CEP-121G

|

ν (cm-1) |

I (%) |

ν (cm-1) |

I (%) |

ν (cm-1) |

I (%) |

ν (cm-1) |

I (%) |

CEP-4G |

2172.23 |

64.9904 |

2043.25 |

51.7671 |

2193.1 |

41.6608 |

2242.97 |

36.4643 |

CEP-31G |

2231.4 |

45.3589 |

1891.26 |

41.6207 |

2027.77 |

40.3978 |

1926.32 |

38.0064 |

CEP-121G |

2177.24 |

100 |

2261.98 |

87.0553 |

1947.03 |

83.1151 |

1778.57 |

51.6624 |

ν = Frequency (cm-1); I = Normalized Intensity (%)

The largest load variation in the APT and Mulliken methods were obtained in the CEP-121G base set, with δ = 2.922 e δ = 2.650, respectively, being δAPT > δMulliken , in all sets of calculated bases, Table 1.

The Table 2 show the maximum absorbance peaks in the CEP-4G, CEP-31G and CEP-121G set basis are present at the frequencies 2172.23 cm-1, with a normalized intensity of 65%; 2231.4 cm-1 and 45.4%; and 2177.24 cm-1 and 100%, respectively.

The Mulliken load method in the UHF-CEP-4G base set; UHF-CEP-31G and UHF-CEP-121G are sufficient to show that the sites of action of the rhodochrosite crystal structure are found in three Oxygen-linked Manganese atoms, which are attached to the central Carbon atom, as well as these. Oxygen atoms and the central carbon.

These Manganese atoms show a slight negative to neutral load shift in the CEP-4G set basis, neutral to positive in the CEP-31G and CEP-121G set basis at the Mulliken charges, Figure 4.

Figure 4. UHF-CEP-4G; UHF-CEP-31G and UHF-CEP-121G for APT and Mulliken, for UHF-CEP-4G basis set, UHF-CEP-31G and UHF-CEP-121G

The charge displacement is strong in the oxygen atoms, especially those near the central carbon, with negative load in all set basis studied, both in the APT and Mulliken charges.

The central carbon atom on all set basis is positively charged in both APT and Mulliken load, except Milliken in CEP-31G, which is neutral.

As might be expected from the charges by APT, the strong positive load manganese atoms, the strong negative load oxygen, the positively charged carbon atom. The manganese atom farthest from the carbon atom has a slight positive to neutral load shift.

The Mulliken load method presents a better result when compared to the APT, in the studied set basis, for protonated rhodochrosite crystal, with a smaller load variation δ = 2,650 u.a for CEP-121G.

The absorption peaks are in a Gaussian between the frequencies 1620 cm -1 and 2520 cm -1, Figure 3D.

The largest load variation in the APT and Mulliken methods were obtained in the CEP-121G base set, with δ = 2.922 e δ = 2.650, respectively, being δAPT > δMulliken , in all sets of calculated basis, Table 1.

The absorption peaks are in a Gaussian between the frequencies 1620 cm-1 and 2520 cm-1.

The Mulliken load method presents a better result when compared to the APT, in the studied set basis, for protonated rhodochrosite crystal, with a smaller load variation δ = 2,650 u.a for CEP-121G.

The maximum absorbance peaks in the CEP-4G, CEP-31G and CEP-121G set basis are present at the frequencies 2172.23 cm-1, with a normalized intensity of 0.65, 2231.4 cm-1 and 0.454 and 2177.24 cm-1 and 1.0 respectively.

Later studies could check the advantages and disadvantages of rhodochrosite in the treatment of cancer through synchrotron radiation, such as one oscillator crystal.

- F. James Holler, Douglas A. Skoog and Stanley R. Crouch. Principles of Instrumental Analysis (6th ed.). Cengage Learning. 200, p. 9. ISBN 978-0-495-01201-6.

- Fox Electronics. Quartz Crystal Theory of Operation and Design Notes. Oscillator Theory of Operation and Design Notes. 2008. Available in: April 16, 2019. URL: https://web.archive.org/web/20110725032851/http://www.foxonline.com/techdata.htm

- R. E. Newnham. Properties of materials. Anisotropy, Simmetry, Structure. Oxford University Press, New York, 2005.

- C. D. Gribble and A. J. Hall. A Practical Introduction to Optical Mineralogy. 1985.

- Creative Commons. (CC-BY 4.0). Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, May 2019. URL: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

- Ricardo Gobato, Marcia Regina Risso Gobato, Alireza Heidari. Rhodochrosite as Crystal Oscillator. Am J Biomed Sci & Res. 2019 - 3(2). AJBSR.MS.ID.000659. DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2019.03.000659.

- Ricardo Gobato, Marcia Regina Risso Gobato, Alireza Heidari. Calculation by UFF method of frequencies and vibrational temperatures of the unit cell of the rhodochrosite crystal International Journal of Advanced Chemistry, 7 (2) (2019) 77-81. doi:10.14419/ijac.v7i1.29176

- Ricardo Gobato, Marcia Regina Risso Gobato, Alireza Heidari. Rhodochrosite as Crystal Oscillator. June 17, 2019. URL:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333817526_Rhodochrosite_as_Crystal_Oscillator?enrichId=rgreq-26dd55b5b6e53fd29f8cf00042058725-XXX&enrichSource=Y292ZXJQYWdlOzMzMzgxNzUyNjtBUzo3NzA3NDE0MTkxMjY3ODRAMTU2MDc3MDQ4MjgwOA%3D%3D&el=1_x_2&_esc=publicationCoverPdf

.

- Ricardo Gobato, Marcia Regina Risso Gobato, Alireza Heidari. Calculation by UFF method of frequencies and vibrational temperatures of the unit cell of the rhodochrosite crystal International. viXra.org, Chemistry, viXra:1908.0294. http://vixra.org/abs/1908.0294.

- Ricardo Gobato, Marcia Regina Risso Gobato, Alireza Heidari. Rhodochrosite as Crystal Oscillator. viXra.org, Condensed Matter, viXra:1908.0295. http://vixra.org/abs/1908.0295.

- Ricardo Gobato, Marcia Regina Risso Gobato, Alireza Heidari, Abhijit Mitra. Rhodochrosite Optical Indicatrix. Peer Res Nest. 2019 - 1(3). PNEST.19.08.020.

- Ricardo Gobato, Marcia Regina Risso Gobato, Alireza Heidari, Abhijit Mitra. Rhodochrosite Optical Indicatrix. viXra.org > Condensed Matter > viXra:1908.0455. URL: http://vixra.org/abs/1908.0455. Available in: Aug 22, 2019.

- China Science Communication. Baidu, 2019. URL: https://baike.baidu.com/pic/%E8%8F%B1%E9%94%B0%E7%9F%BF/689440/0/ea85a945fe4fae32cefca358?fr=lemma&ct=single#aid=20301545&pic=148f28d3ccde9a143bf3cf58. Avaliable in: March 21, 2019.

- N. Levine. Quantum Chemistry. Pearson Education (Singapore) Pte. Ltd., Indian Branch, 482 F. I. E. Patparganj, Delhi 110 092, India, 5th ed. edition, 2003.

- Szabo and N. S. Ostlund. Modern Quantum Chemistry. Dover Publications, New York, 1989.

- M. S. Gordon et al. General atomic and molecular electronic structure system (GAMESS). J. Comput. Chem., 14:1347–1363, 1993.

- K. Ohno, K. Esfarjani and Y. Kawazoe. Computational Material Science. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1999.

- K. Wolfram and M. C. Hothausen. Introduction to DFT for Chemists. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. New York, 2nd ed. edition, 2001.

- P. Hohenberg and W. Kohn. Inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev., (136):B864–B871, 1964.

- W. Kohn and L. J. Sham. Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys. Rev., (140):A1133, 1965.

- R. S. Mulliken, J. Chem. Phys. 1955 23, 1833-1840.

- G. Csizmadia, Theory and Practice of MO Calculations on Organic Molecules, Elsevier, Amsterdam, 1976.

- Ferreira, M. M. C. J. Phys. Chem. 1990, 94, 3220-3223.

- Biarge, J. F.; Herranz, J.; Morcillo, J. An. R. Soc. Esp. Fis. Quim. Ser. A 1961, A57,81.

- Person, W. B.: Newton, J. H. J. Chem. Phys. 1974, 61. 1040.

- King, W. T.; Mast, G. B. J. Phys. Chem. 1976,80,2521.

- King, W. T. Vibrational Intensities in Infrared and Ramon Spectra: Person, W. B., Zerbi, G.. Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 1982; Chapter 6.

- Person, W. B.; Zilles, B.; Rogers, J. D.; Maia, R. G. A. J. Mol. Struct.1982, 80, 297.

- Zilles. B. A. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Florida, 1980.

- Zilles, B. A.; Person, W. 8. J. Chem. Phys. 1983, 79, 65.

- Creative Commons, (CC BY 4.0), https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. “List of Intel Core i3 microprocessors”, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Intel_Core_i3_microprocessors, Available in: August 30, 2018.

- __________.___ “Ivy Bridge”, https://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ivy_Bridge, Access in: August 31, 2018.

- __________.___ “Ubuntu (operating system)”, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ubuntu_(operating_system), Available in: August 31, 2018.

- M. S. Gordon and M. W. Schmidt. Advances in electronic structure theory: GAMESS a decade later. Theory and Applications of Computational Chemistry: the first forty years. Elsevier. C. E. Dykstra, G. Frenking, K. S. Kim and G .E. Scuseria (editors), pages 1167–1189, 2005. Amsterdam.

- R. Gobato, A. Gobato, D. F. G. Fedrigo, “Inorganic arrangement crystal beryllium, lithium, selenium and silicon”. In XIX Semana da Física. Simpósio Comemorativo dos 40 anos do Curso de Física da Universidade Estadual de Londrina, Brazil, 2014. Universidade Estadual de Londrina (UEL).

- R. Gobato, “Benzocaína, um estudo computacional”, Master’s thesis, Universidade Estadual de Londrina (UEL), 2008.

- R. Gobato, “Study of the molecular geometry of Caramboxin toxin found in star flower (Averrhoa carambola L.)”. Parana J. Sci. Edu, 3(1):1–9, January 2017.

- R. Gobato, A. Gobato, D. F. G. Fedrigo, “Molecular electrostatic potential of the main monoterpenoids compounds found in oil Lemon Tahiti - (Citrus Latifolia Var Tahiti)”. Parana J. Sci. Edu., 1(1):1–10, November 2015.

- R. Gobato, D. F. G. Fedrigo, A. Gobato, “Allocryptopine, Berberine, Chelerythrine, Copsitine, Dihydrosanguinarine, Protopine and Sanguinarine. Molecular geometry of the main alkaloids found in the seeds of Argemone Mexicana Linn”. Parana J. Sci. Edu., 1(2):7–16, December 2015.

- R. Gobato, A. Heidari, “Infrared Spectrum and Sites of Action of Sanguinarine by Molecular Mechanics and ab initio Methods”, International Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences. Vol. 2, No. 1, 2018, pp. 1-9. doi: 10.11648/j.ijaos.20180201.11

- R. Gobato, D. F. G. Fedrigo, A. Gobato, “Molecular geometry of alkaloids present in seeds of mexican prickly poppy”. Cornell University Library. Quantitative Biology, Jul 15, 2015. arXiv:1507. 05042.

- R. Gobato, A. Gobato, D. F. G. Fedrigo, “Study of the molecular electrostatic potential of D-Pinitol an active hypoglycemic principle found in Spring flower Three Marys (Bougainvillea species) in the Mm+ method”. Parana J. Sci. Educ., 2(4):1–9, May 2016.

- R. Gobato, D. F. G. Fedrigo, A. Gobato, “Avro: key component of Lockheed X-35”, Parana J. Sci. Educ., 1(2):1–6, December 2015.

- R. Gobato, D. F. G. Fedrigo, A. Gobato, “LOT-G3: Plasma Lamp, Ozonator and CW Transmitter”, Ciencia e Natura, 38(1), 2016.

- R. Gobato, “Matter and energy in a non-relativistic approach amongst the mustard seed and the faith. A metaphysical conclusion”. Parana J. Sci. Educ., 2(3):1–14, March 2016.

- R. Gobato, A. Gobato, D. F. G. Fedrigo, “Harnessing the energy of ocean surface waves by Pelamis System”, Parana J. Sci. Educ., 2(2):1–15, February 2016.

- R. Gobato, A. Gobato, D. F. G. Fedrigo, “Mathematics for input space probes in the atmosphere of Gliese 581d”, Parana J. Sci. Educ., 2(5):6–13, July 2016.

- R. Gobato, A. Gobato, D. F. G. Fedrigo, “Study of tornadoes that have reached the state of Parana”. Parana J. Sci. Educ., 2(1):1–27, 2016.

- R. Gobato, M. Simões F. “Alternative Method of RGB Channel Spectroscopy Using a CCD Reader”, Ciencia e Natura, 39(2), 2017.

- R. Gobato, A. Heidari, “Calculations Using Quantum Chemistry for Inorganic Molecule Simulation BeLi2SeSi”, Science Journal of Analytical Chemistry, 5(5):76–85, September 2017.

- M. R. R. Gobato, R. Gobato, A. Heidari, “Planting of Jaboticaba Trees for Landscape Repair of Degraded Area”, Landscape Architecture and Regional Planning, 3(1):1–9, March 18, 2018.

- R. Gobato, “The Liotropic Indicatrix”, 2012, 114 p. Thesis (Doctorate in Pysics). Universidade Estadual de Londrina, Londrina, 2012.

- R. Gobato, A. Heidari, “Calculations Using Quantum Chemistry for Inorganic Molecule Simulation BeLi2SeSi”, Science Journal of Analytical Chemistry, Vol. 5, No. 6, Pages 76–85, 2017.

- M. R. R Gobato, R. Gobato, A. Heidari, “Planting of Jaboticaba Trees for Landscape Repair of Degraded Area”, Landscape Architecture and Regional Planning, Vol. 3, No. 1, 2018, Pages 1–9, 2018.

- R. Gobato, A. Heidari, “Molecular Mechanics and Quantum Chemical Study on Sites of Action of Sanguinarine Using Vibrational Spectroscopy Based on Molecular Mechanics and Quantum Chemical Calculations”, Malaysian Journal of Chemistry, Vol. 20(1), 1–23, 2018.

- Heidari, R. Gobato. “A Novel Approach to Reduce Toxicities and to Improve Bioavailabilities of DNA/RNA of Human Cancer Cells–Containing Cocaine (Coke), Lysergide (Lysergic Acid Diethyl Amide or LSD), Δ⁹–Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) [(–)–trans–Δ⁹–Tetrahydrocannabinol], Theobromine (Xantheose), Caffeine, Aspartame (APM) (NutraSweet) and Zidovudine (ZDV) [Azidothymidine (AZT)] as Anti–Cancer Nano Drugs by Coassembly of Dual Anti–Cancer Nano Drugs to Inhibit DNA/RNA of Human Cancer Cells Drug Resistance”, Parana Journal of Science and Education, v. 4, n. 6, pp. 1–17, 2018.

- Heidari, R. Gobato, “Ultraviolet Photoelectron Spectroscopy (UPS) and Ultraviolet–Visible (UV–Vis) Spectroscopy Comparative Study on Malignant and Benign Human Cancer Cells and Tissues with the Passage of Time under Synchrotron Radiation”, Parana Journal of Science and Education, v. 4, n. 6, pp. 18–33, 2018.

- R. Gobato, A. Heidari, “Using the Quantum Chemistry for Genesis of a Nano Biomembrane with a Combination of the Elements Be, Li, Se, Si, C and H”, J Nanomed Res., 7 (4): 241-252, 2018.

- S. K. Agarwal, S. Roy, P. Pramanick, P. Mitra, R. Gobato, A. Mitra, “Marsilea quadrifolia: A floral species with unique medicinal properties”, Parana J. Sci. Educ., v.4, n.5, (15–20), July 1, 2018.

- Mitra, S. Zaman, R. Gobato. “Indian Sundarban Mangroves: A potential Carbon Scrubbing System”. Parana J. Sci. Educ., v.4, n.4, (7–29), June 17, 2018.

- O. Yarman, R. Gobato, T. Yarman, M. Arik. “A new Physical constant from the ratio of the reciprocal of the “Rydberg constant” to the Planck length”. Parana J. Sci. Educ., v.4, n.3, (42–51), April 27, 2018.

- R. Gobato, M. Simões F., “Alternative Method of Spectroscopy of Alkali Metal RGB”, Modern Chemistry. Vol. 5, No. 4, 2017, pp. 70–74. https://doi:10.11648/j.mc.20170504.13.

- D. F. G. Fedrigo, R. Gobato, A. Gobato, “Avrocar: a real flying saucer”, Cornell University Library. 24 Jul 2015. arXiv:1507.06916v1 [physics.pop–ph].

- M, Simões F., A. J. Palangana, R. Gobato, O. R. Santos, "Micellar shape anisotropy and optical indicatrix in reentrant isotropic—nematic phase transitions", The Journal of Chemical Physics, 137, 204905 (2012); https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4767530.

- Heidari, R. Gobato, “Putrescine, Cadaverine, Spermine and Spermidine–Enhanced Precatalyst Preparation Stabilization and Initiation (EPPSI) Nano Molecules”, Parana Journal of Science and Education (PJSE)–v.4, n.5, (1–14) July 1, 2018.

- R. Gobato, A. Heidari, “Molecular Mechanics and Quantum Chemical Study on Sites of Action of Sanguinarine Using Vibrational Spectroscopy Based on Molecular Mechanics and Quantum Chemical Calculations”, Malaysian Journal of Chemistry, Vol. 20 (1), 1–23, 2018.

- R. Gobato, A. Heidari, A. Mitra, “The Creation of C13H20BeLi2SeSi. The Proposal of a Bio–Inorganic Molecule, Using Ab Initio Methods for the Genesis of a Nano Membrane”, Arc Org Inorg Chem Sci 3 (4). AOICS.MS.ID.000167, 2018.

- R. Gobato, A. Heidari, A. Mitra, “Using the Quantum Chemistry for Genesis of a Nano Biomembrane with a Combination of the Elements Be, Li, Se, Si, C and H”, ResearchGate, See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326201181, 2018.

- Heidari, R. Gobato, “First–Time Simulation of Deoxyuridine Monophosphate (dUMP) (Deoxyuridylic Acid or Deoxyuridylate) and Vomitoxin (Deoxynivalenol (DON)) ((3α,7α)–3,7,15–Trihydroxy–12,13–Epoxytrichothec–9–En–8–One)–Enhanced Precatalyst Preparation Stabilization and Initiation (EPPSI) Nano Molecules Incorporation into the Nano Polymeric Matrix (NPM) by Immersion of the Nano Polymeric Modified Electrode (NPME) as Molecular Enzymes and Drug Targets for Human Cancer Cells, Tissues and Tumors Treatment under Synchrotron and Synchrocyclotron Radiations”, Parana Journal of Science and Education, Vol. 4, No. 6, pp. 46–67, 2018.

- R. Gobato, M. R. R. Gobato, A. Heidari, A. Mitra, “Spectroscopy and Dipole Moment of the Molecule C13H20BeLi2SeSi via Quantum Chemistry Using Ab Initio, Hartree–Fock Method in the Base Set CC–pVTZ and 6–311G**(3df, 3pd)”, Arc Org Inorg Chem Sci 3 (5), Pages 402–409, 2018.

- R. Gobato, M. R. R. Gobato, A. Heidari, A. Mitra, “Spectroscopy and Dipole Moment of the Molecule C13H20BeLi2SeSi via Quantum Chemistry Using Ab Initio, Hartree–Fock Method in the Base Set CC–pVTZ and 6–311G**(3df, 3pd)”, American Journal of Quantum Chemistry and Molecular Spectroscopy, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 9–17, 2018.

- R. Gobato, M. R. R. Gobato, A. Heidari, “Raman Spectroscopy Study of the Nano Molecule C13H20BeLi2SeSi Using ab initio and Hartree–Fock Methods in the Basis Set CC–pVTZ and 6–311G** (3df, 3pd)”, International Journal of Advanced Engineering and Science, Volume 7, Number 1, Pages 14–35, 2019.

- Heidari, R. Gobato, “Evaluating the Effect of Anti–Cancer Nano Drugs Dosage and Reduced Leukemia and Polycythemia Vera Levels on Trend of the Human Blood and Bone Marrow Cancers under Synchrotron Radiation”, Trends in Res, Volume 2 (1): 1–8, 2019.

- Heidari, R. Gobato, “Assessing the Variety of Synchrotron, Synchrocyclotron and LASER Radiations and Their Roles and Applications in Human Cancer Cells, Tissues and Tumors Diagnosis and Treatment”, Trends in Res, Volume 2 (1): 1–8, 2019.

- Heidari, R. Gobato, “Pros and Cons Controversy on Malignant Human Cancer Cells, Tissues and Tumors Transformation Process to Benign Human Cancer Cells, Tissues and Tumors”, Trends in Res, Volume 2 (1): 1–8, 2019.

- Heidari, R. Gobato, “Three–Dimensional (3D) Simulations of Human Cancer Cells, Tissues and Tumors for Using in Human Cancer Cells, Tissues and Tumors Diagnosis and Treatment as a Powerful Tool in Human Cancer Cells, Tissues and Tumors Research and Anti–Cancer Nano Drugs Sensitivity and Delivery Area Discovery and Evaluation”, Trends in Res, Volume 2 (1): 1–8, 2019.

- Heidari, R. Gobato, “Investigation of Energy Production by Synchrotron, Synchrocyclotron and LASER Radiations in Human Cancer Cells, Tissues and Tumors and Evaluation of Their Effective on Human Cancer Cells, Tissues and Tumors Treatment Trend”, Trends in Res, Volume 2 (1): 1–8, 2019.

- Heidari, R. Gobato, “High–Resolution Mapping of DNA/RNA Hypermethylation and Hypomethylation Process in Human Cancer Cells, Tissues and Tumors under Synchrotron Radiation”, Trends in Res, Volume 2 (2): 1–9, 2019.

- R. Gobato, M. R. R. Gobato, A. Heidari, “Storm Vortex in the Center of Paraná State on June 6, 2017: A Case Study”, Sumerianz Journal of Scientific Research, Vol. 2, No. 2, Pages 24–31, 2019.

- R. Gobato, M. R. R. Gobato, A. Heidari, “Attenuated Total Reflection–Fourier Transform Infrared (ATR–FTIR) Spectroscopy Study of the Nano Molecule C13H20BeLi2SeSi Using ab initio and Hartree–Fock Methods in the Basis Set RHF/CC– pVTZ and RHF/6–311G** (3df, 3pd): An Experimental Challenge to Chemists”, Chemistry Reports, Vol. 2, No. 1, Pages 1–26, 2019.

- R. Gobato, M. R. R. Gobato, A. Heidari, A. Mitra, “New Nano–Molecule Kurumi–C13H 20BeLi2SeSi/C13H19BeLi2SeSi, and Raman Spectroscopy Using ab initio, Hartree–Fock Method in the Base Set CC–pVTZ and 6–311G** (3df, 3pd)”, J Anal Pharm Res. 8 (1): 1-6, 2019.

- R. Gobato, M. R. R. Gobato, A. Heidari, “Evidence of Tornado Storm Hit the Counties of Rio Branco do Ivaí and Rosario de Ivaí, Southern Brazil”, Sci Lett 7 (1), 9 Pages, 2019.

- Moharana Choudhury, Pardis Fazli, Prosenjit Pramanick, Ricardo Gobato, Sufia Zaman, Abhijit Mitra, “Sensitivity of the Indian Sundarban mangrove ecosystem to local level climate change”, Parana Journal of Science and Education. Vol. 5, No. 3, 2019, pp. 24-28.

- Arpita Saha, Ricardo Gobato, Sufia Zaman, Abhijit Mitra, “Biomass Study of Mangroves in Indian Sundarbans: A Case Study from Satjelia Island”, Parana Journal of Science and Education. Vol. 5, No. 2, 2019, pp. 1-5.

- Nabonita Pal, Arpan Mitra, Ricardo Gobato, Sufia Zaman, Abhijit Mitra, “Natural Oxygen Counters in Indian Sundarbans, the Mangrove Dominated World Heritage Site”, Parana Journal of Science and Education. Vol. 5, No. 2, 2019, pp. 6-13.

- Ricardo Gobato, Victoria Alexandrovna Kuzmicheva, Valery Borisovich Morozov, ―Einstein's hypothesis is confirmed by the example of the Schwarzschild problem”, Parana Journal of Science and Education, Vol. 5, No. 1, 2019, pp. 1-6.

- Sufia Zaman, Ricardo Gobato, Prosenjit Pramanick, Pavel Biswas, Uddalok Chatterjee, Shampa Mitra, Abhijit Mitra, “Water quality of the River Ganga in and around the city of Kolkata during and after Goddess Durga immersion”, Parana Journal of Science and Education, Vol. 4, No. 9, 2018, pp. 1-7.

- Ozan Yarman, Metin Arik, Ricardo Gobato, Tolga Yarman, Clarification of “Overall Relativistic Energy” According to Yarman’s Approach.”, Parana Journal of Science and Education., v.4, n.8, 2018, pp. 1-10.

- Sufia Zaman, Utpal Pal, Ricardo Gobato, Alekssander Gobato, Abhijit Mitra, “The Changing Trends of Climate in Context to Indian Sundarbans”, Parana Journal of Science and Education, Vol. 4, No. 7, 2018, pp. 24-28.

- Suresh Kumar Agarwal, Sitangshu Roy, Prosenjit Pramanick, Prosenjit Mitra, Ricardo Gobato and Abhijit Mitra. Parana Journal of Science and Education. Vol. 4, No. 5, 2018, pp. 15-20.

- Ricardo Gobato and Marcia Regina Risso Gobato, “Evidence of Tornadoes Reaching the Countries of Rio Branco do Ivai and Rosario de Ivai, Southern Brazil on June 6, 2017”, Climatol Weather Forecasting 2018, 6:4. DOI: 10.4172/2332-2594.1000242.

- Ricardo Gobato. “New Nano-Molecule Kurumi and Raman Spectroscopy using ab initio, Hartree-Fock Method” Am J Biomed Sci & Res. 2019 - 2(4). AJBSR.MS.ID.000594. DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2019.02.000594.

- D. L. Graf, Rhodochrosite, Crystallographic tables for the rhombohedral carbonates, American Mineralogist 46 (1961) 1283-1316.

- E. N. Maslen, V. A. Streltsov, N. R. Streltsova, N. Ishizawa, Electron density and optical anisotropy in rhombohedral carbonates. III. Synchrotron X-ray studies of CaCO3, MgCO3 and MnCO3, Acta Crystallographica B51 (1995) 929-939.

- R. Wyckoff, The crystal structures of some carbonates of the calcite group, American Journal of Science 50 (1920) 317-360.

- D. Marcus, D. E. Hanwell, D. C. Curtis, T. V Lonie, E. Zurek, G. R. Hutchison, “Avogadro: An advanced semantic chemical editor, visualization, and analysis platform” Journal of Cheminformatics 2012, 4:17.

- J. Cioslowski, Phys. Rev. Lett., 1989, 62, 1469.

- Paul von Ragu Schleyer, Encyclopedia of computational chemistry, New York, J. Wiley, 1998.

- Mulliken, R. S. "Electronic Population Analysis on LCAO-MO Molecular Wave Functions. I". The Journal of Chemical Physics. (1955). 23 (10): 1833–1840. Bibcode:1955JChPh..23.1833M. doi:10.1063/1.1740588.

- G. Csizmadia, Theory and Practice of MO Calculations on Organic Molecules, Elsevier, Amsterdam, 1976.

- W. J. Stevens, H. Basch, and M. Krauss, “Compact effective potentials and efficient shared-exponent basis-sets for the 1st-row and 2nd-row atoms,” J. Chem. Phys., 81 (1984) 6026-33. DOI: 10.1063/1.447604.

- W. J. Stevens, M. Krauss, H. Basch, and P. G. Jasien, “Relativistic compact effective potentials and efficient, shared-exponent basis-sets for the 3rd-row, 4th-row, and 5th-row atoms,” Can. J. Chem., 70 (1992) 612-30. DOI: 10.1139/v92-085

- T. R. Cundari and W. J. Stevens, “Effective core potential methods for the lanthanides,” J. Chem. Phys., 98 (1993) 5555-65. DOI: 10.1063/1.464902.

and a spin function (either

and a spin function (either  or

or  ).

). is given by the variation theorem as

is given by the variation theorem as  where D is the Slater-determinant Hartree-Fock wave function and

where D is the Slater-determinant Hartree-Fock wave function and  and

and  are given by

are given by

. The operator

. The operator  and two-electron operators

and two-electron operators  ; we have

; we have  , where

, where  and

and  . The Hamiltonian

. The Hamiltonian  replaces

replaces  in

in

.

.

. [5]

. [5]

is N - the total number of electrons. The Mulliken population analysis aims first of all to distribute the N electrons on all the basic functions. This is done by taking the diagonal elements of

is N - the total number of electrons. The Mulliken population analysis aims first of all to distribute the N electrons on all the basic functions. This is done by taking the diagonal elements of  this simplifies the operation to a sum on a line. This defines the gross orbital population (GOB) as:

this simplifies the operation to a sum on a line. This defines the gross orbital population (GOB) as:

lie on N and then divide the total number of electrons between the basic functions. It then remains to sum these terms on all the basic functions of a given atom A in order to obtain the gross atomic population (GAP). The integral of the GAPA terms also gives N. The load, QA, is then defined as the difference between the number of electrons on the free isolated atom, which is the atomic number ZA, and the raw atomic population:

lie on N and then divide the total number of electrons between the basic functions. It then remains to sum these terms on all the basic functions of a given atom A in order to obtain the gross atomic population (GAP). The integral of the GAPA terms also gives N. The load, QA, is then defined as the difference between the number of electrons on the free isolated atom, which is the atomic number ZA, and the raw atomic population:

and

and  so that

so that

are of atomic origin where the first one, involving the net atomic charge, is the only term with a classical counterpart. The second term resembles Coulson’s atomic dipole, and the integral

are of atomic origin where the first one, involving the net atomic charge, is the only term with a classical counterpart. The second term resembles Coulson’s atomic dipole, and the integral  is the distance from the centroid of the hybrid orbital to nucleus A. For the third term, the integral

is the distance from the centroid of the hybrid orbital to nucleus A. For the third term, the integral  is the distance of the center of charge from the midpoint of the chemical bond A-B. This contribution to the dipole moment has been referred to as the homopolar dipole [21] by Mulliken. As can be seen, the dipole moment has been partitioned into three contributions: the net atomic charge, the atomic dipole, and the homopolar dipole. Since the density matrix is invariant with respect to the choice of origin and since the sum of all net atomic charges vanishes, this partitioning of the dipole moment does not depend on the choice of origin for the system [5,23].

is the distance of the center of charge from the midpoint of the chemical bond A-B. This contribution to the dipole moment has been referred to as the homopolar dipole [21] by Mulliken. As can be seen, the dipole moment has been partitioned into three contributions: the net atomic charge, the atomic dipole, and the homopolar dipole. Since the density matrix is invariant with respect to the choice of origin and since the sum of all net atomic charges vanishes, this partitioning of the dipole moment does not depend on the choice of origin for the system [5,23].

in molecule, the quantities

in molecule, the quantities  where

where  and

and  form the APT, represent by a

form the APT, represent by a  matrix

matrix

, the first two terms are the only classical contributions, one of them being the Mulliken net charge of atom a in its equilibrium position,

, the first two terms are the only classical contributions, one of them being the Mulliken net charge of atom a in its equilibrium position,  , and the other being the "charge flux" corresponding to charge migration as the chemical bond involving the

, and the other being the "charge flux" corresponding to charge migration as the chemical bond involving the

depend on

depend on  .

.