porphyria, acute intermittent porphyria, aip, hemin

Porphyrias are inherited defects in the biosynthesis of heme.

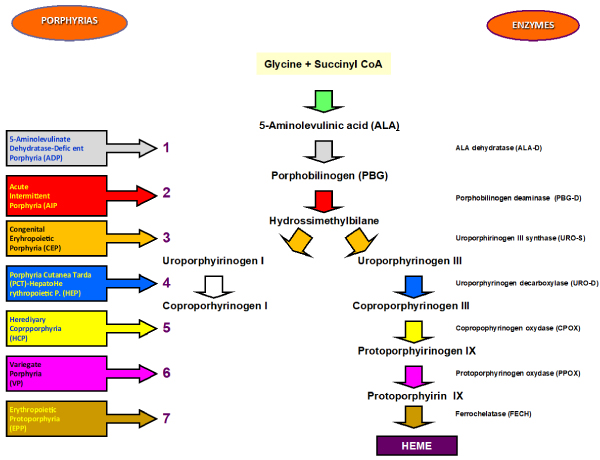

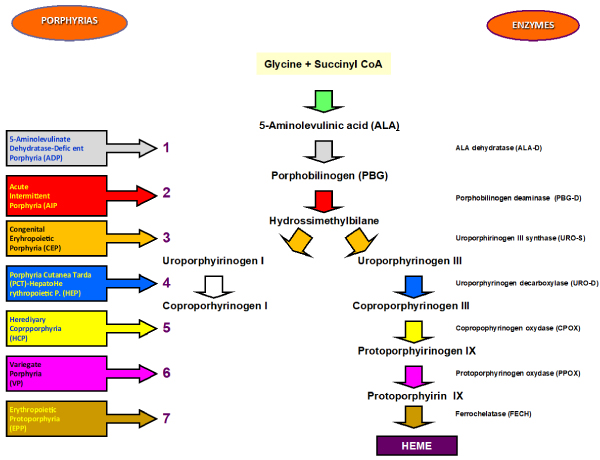

The porphyrias are morbid conditions caused by defects in the metabolism of porphyrins, group of pigments composed of four pyrrole nuclei connected to each other by methinic bridges. Porphyrins are widespread in the animal and plant world as chlorophyll, and as heme group, a cofactor of hemoproteins such hemoglobin, cytochromes, catalase and peroxidase. The nitrogen atoms of each pyrrole ring are bound to a metaal atom such as iron in gemoglobin or magnesium in chlorophyll. Porphyrins can be classified into five categories: uroporphyrins, coproporphyrins, etioporphyrins, protoporphyrins, haematoporphyrin. Their synthesis takes placein the liver and in haematopoietic tissue cells. The incorrect or excessive production of porphyrins leads to pathologies called Porphyrias. Porphyrias are the result of partial defects in one or more of the seven enzymes involved in heme biosynthesis (Figure 1) [1-3].

Figure 1. Synoptic framework of human porphyrias and of the deficient enzyme responsible for the disease

Attacks in Acute Intermittent Porphyria (AIP) are characterized by abdominal pain, neurological disturbances and psychiatric disorders and, in severe cases, they may lead to respiratory paralysis and coma [4-7].

In some cases the metabolic alteration can be acquised [8-10].

Porphyria has a mortality of 20-25% within the first five years since the first attack; rare in children and after the fifth decade.

The reasons behind the attacks can be several: drugs, alcohol, stress, fasting, menstrual cycle, infections.

The prevalence of acute porphyria is 10,1/100000 (according Orphanet, November 2016).

Renal involvement in acute porphyrias is represented by hyponatremia, urinary retention, tubulo-interstitial nephropathy, hypertension and chronic kidney disease. Most of our patients were affected by renal colic associated with pallor, nausea, vomiting, fever, acute retention of urine and dark urine [11-14].

An acute attack may be preceded by a period of different-grade behavioural changes such as anxiety, irritability, restlessness and insomnia abd it may evolve rapidly into symptoms of severe autonomic and acute motor and sensory neuropathy (resembling Guillan-Barrw Syndrome) is quite common. It can progress to general paralysis leading to severe respiratory impairment up to death from cardiorespiratory arrest [15-17].

A 68-year-old women, undergoing tri-weekly hemodialysis since January 2011 (32 months) for Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) due to undiagnosed nephropathy has been diagnosed with Acute Intermittent Porphyria (AIP) after a family screening.

In October 2012 she underwent superior-external quadrantectomy of the right breast for invasive ductal carcinoma, grade II, score 6 [1-3] and intraductal papillomas (G2 pT2 pNOs).

In February 2013 she underwent subtotal thyroidectomy for goiter with focus of papillary microcarcinoma and subtotal parathyroidectomy for hyperplastic parathyroid.

In September 2013 she was admitted to the division of Nephrology because of abdominal pain, constipation and uncontrolled hypertension. Since she had no diuresis, plasma porphyrins were measured at a peak of 619 nm.

The patient reported depression and progressive muscle weakness in legs and then, the following day, even in arms, defining a medical case of flaccid tetraparesis. In suspect of poliradicoloneuritis, a lumbar puncture was made and it was negative. Two days later, hemin (Normosang) was administered through femoral vein catheter in order not to damage her arteriovenous fistula, at a dose of 3 mg/kg/24h for 4 straight days, and then bi-weekly for the following 2 months, during which she was moved to the division of Rehabilitation Medicine and Neuro-rehabilitation Unit where she started a rehabilitation plan since her limbs strength had a MRC-score of 0.

Functional evaluation was assessed by Barthel scale (BS), at admission and at discharge. The BS quantifies global functional recovery and the degree of independence of any help (physical, verbal,…) in activities of daily living. It ranges from 0 to 100, with 0 indicating a totally dependent patient in bedridden state and 100 indicating that the patient is fully independent. Items are divided into groups that relate to self-care (feeding, grooming, bathing, dressing, bowel and bladder care and toilet use) and mobility (ambulation, transfers and stairs climbing). Muscular strength of involved paretic muscles was ascertained by use of the Medical Research Council (MRC) scale according to De Jonghe’s method that, for each limb, evaluates muscular groups of three muscles: deltoid, biceps and wrist’s extensor (upper limb); iliopsoas, quadriceps femoris and tibialis anterior (lower limb). The evaluation was performed at admission, 2, 4 weeks and at discharge. According to MRC scale, strength ranges from 0 (paralysis) to 5 (normal strength) for any muscle, so for each muscle group the score ranges from 0 and 15 0-5 for muscle bundle for 3 muscle groups for the 4 limbs respectively), making the overall score range from 0 to 60. A score less than 24 shows severe muscular deficit, whereas an MRC score with 48 or higher was considered a very mild weakness or normal. The subject underwent rehabilitation including joint mobilization, muscular stretching, proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation, and occupational therapy. Furthermore, the patients had low frequency (4 Hz) electrical stimulation (ES) done, through COMPEX instrument, with the following physical parameters: 90 mA intensity and rectangular pulses of 0.2 ms were applied on quadriceps and tibialis anterior of lower limbs one hour daily, six day a week for one month. The patient underwent rehabilitation including electrical stimulation and occupational therapy [18-20].

At admission, BS score was 25 indicating severe disability. Likewise, neurological picture showed severe strength impairment characterized by tetraplegia. MRC score was 0 either both upper and lower limbs. After the administration of hemin and rehabilitation treatment, muscular deficit progressively improved and MRC scores were 24, 36 and 50 at 2, 4 weeks and at discharge, respectively. Likewise, good functional outcome was also observed as BS scores were 45, 65 and 90 at 2, 4 weeks and at discharge, respectively. Equally, functional appearance is significantly improved as observed from the increase of BS scores to 45, 65 and 90, at 2, 4 weeks and at discharge, respectively compared at score of 25 at admission (Table 1).

Table 1. *Cumulative value of upper and lower limb strength according to De Jonghe method BS from 0 to 100 (0= total dipendence – 100 = fully indipendence) (Barthel scale).

| |

2 weeks |

4 weeks |

discharge |

BS |

45 |

65 |

90 |

MRC* |

24 |

36 |

50 |

MRC* from 0 to 60 (<48 = muscular deficit – > 48=muscle weakness) (Medical Research Council)

Three months after the beginning of the disease, she was given hemin for 4 straight days due to hyponatremia (132 mmol/l) and then monthly in addition to physical rehabilitation, until she improved her muscle strength and motor skills to ensure can go back to an autonomous life.

Currently, from a clinical and functional point of view, the patient presents: a) a good muscle tropism and tone, b) good articular function and c) self-walking capability with enlarged base at the slightest uncertainty. Right now the patient is given hemin every 2 months and we’re planning to cut down even more the administration of hemin in the following months. The patient will keep on doing physical treatment and will follow a normocaloric, hyperglucidic diet with the addition of maltodestrins. Currently she is undergoing hemin therapy every 4 months and tri-weekly hemodialysis.

Porphyrias belong to the category of those “submerged” diseases whose prevalence will change over time as a functioin of our ability to diagnose them.

The diagnosis of porphyrias is not easy because only a small percentage of genetic defects carriers shows a full-blown disease during thei lifetime, plus these defects are very heterogeneous and are affected by the exposure to endogenous and exogenous environmental factors that are capable of aggravating the symptoms.

Moreover many of those symptoms are common to many different pathologies and have a transitory nature that makes theit biochemical alterations detectable only during the acute phases or during the re-exacerbation periods of the disease. Thus it might take a lot of time to make the right diagnosis.

An accurate diagnosis is mandatory to provide immediate proper therapeutic approach, in order to prevent the use od potentially unsafe drugs, usually precipitating the clinical picture especially in the presence of life-threatening symptoms

Diagnosis of individual porphyrias requires a correct analysis of porphyrins and porphyrin precursors in appropriate (urine, stools, blood) samples, often supported only in porphyria clinical specialist centres [4,21-25].

The correct identification of patients strongly suggests an in-depth study of their relatives (to date mostly by means of DNA assays) in order to identify potential diseases carriers who shoud be informed about their possible health risk when exposed to potential triggering factors.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. For this type of study formal consent is not required.

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the Study. Additional informed consent was obtained from all individual participants for whom identifying information is included in this chapter.

- Young JW, Conte ET (1991) Porphyrias and porphyrins. Int J Dermatol 30: 399-406. [Crossref]

- Heme and porphyrin metabolism. https://www.med.unibs.it/marchesi/heme.html

- Woods JS (1988) Regulation of porphyrin and heme metabolism in the kidney. Semin Hematol 25: 336-348. [Crossref]

- Ventura P, Cappellini MD, Rocchi E (2009) The acute porphyrias: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge in internal and emergency medicine. Intern Emerg Med 4: 297-308. [Crossref]

- Puy H, Gouya L, Deybach JC (2010) Porphyrias. Lancet 365: 924-37.

- Kauppinen R (2005) Porphyrias. Lancet 365: 241-252. [Crossref]

- Thunell S (2000) Porphyrins, porphirin metabolism and porphyrias. Update. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 60: 509-540.

- Ventura P, Le Porfirie (2011) In Brunetti P, Santeusanio F (Eds) Trattato di Medicina Interna. Volume Malattie delle Ghiandole Endocrine, del Metabolismo e della Nutrizione. Padova: Piccin Nuova Libraria pp. 931-952

- Ventura E, Rocchi E (2001) Le Porfirie. In: Teodori 2000 Trattato di Medicina Interna Guarini G, Fiorelli G, Malliani A, Violi E, Volpe M (Eds) Società Editrice Universo: Italy 2: 2301-2334.

- Elder GH, Hift RJ, Meissner PN (1997) The acute porphyrias. Lancet 349: 1613-1617. [Crossref]

- Mydlík M, Derzsiová K (2011) Kidney damage in acute intermittent porphyria. Przegl Lek 68: 610-613.

- Andersson C, Wikberg A, Stegmayr B, Lithner F (2000) Renal symptomatology in patients with acute intermittent porphyria. A population-based study. J Intern Med 248: 319-325. [Crossref]

- Marsden JT, Chowdhury P, Wang J, Deacon A, Dutt N, et al. (2008) Acute intermittent porphyria and chronic renal failure. Clin Nephrol 69: 339-346. [Crossref]

- O'Mahoney D, Wathen CG (1996) Hypertension in porphyria--an understated problem. QJM 89: 161-162. [Crossref]

- Solinas C, Vajda FJ (2008) Neurological complications of porphyria. J Clin Neurosci 15: 263-268. [Crossref]

- Pischik E, Kauppinen R (2009) Neurological manifestations of acute intermittent porphyria. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 55: 72-83. [Crossref]

- Meyer UA, Schuurmans MM, Lindberg RL (1998) Acute porphyrias: pathogenesis of neurological manifestations. Semin Liver Dis 18: 43-52. [Crossref]

- De Jonghe B, Sharshar T, Lefaucheur JP, Authier FJ, Durand-Zaleski I, et al. (2002) Paresis acquired in the intensive care unit: a prospective multicenter study. JAMA 288: 2859-2867. [Crossref]

- Mahoney FI, Bathel DW (1965) Functional evaluation: The Barthel Index Md State Med J 14: 61-65. [Crossref]

- Medical Research Council (1976) Aids to the investigation of the peripheral nervous system. Her Majesty’s Stationary Office, London.

- Kauppinen R (2005) Porphyrias. Lancet 365: 241-252.

- Thunell S, Harper P, Brock A, Petersen NE (2000) Porphyrins, porphyrin metabolism and porphyrias. II. Diagnosis and monitoring in the acute porphyrias. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 60: 541-559. [Crossref]

- Hindmarsh JT (2003) The porphyrias, appropriate test selection. Clin Chim Acta 333: 203-207. [Crossref]

- Hift RJ (1999) The diagnosis of porphyria. S Afr Med J 89: 611-614.

- Hindmarsh JT, Oliveras L, Greenway DC (1999) Biochemical differentiation of the porphyrias. Clin Biochem 32: 609-619. [Crossref]