Abstract

Introduction

Little research has been devoted to preschool obesity prevention in Tunisia. Our purpose was to evaluate feasibility and effects of an intervention program for preschoolers, parents and kindergarten staffs aiming to increase the proportion of children doing physical activity and those with balanced eating habits.

Methods

We carried out a quasi-experimental intervention study with two groups: A control group and an intervention group. The participants were preschoolers aged 4 to 5 years, their parents and the kindergarten staffs. The sample size to select children was based on a significance level of α = 5% and a power 1-β= 80% and 10% change in physical activity practice and balanced eating habits. In each group, we made a pre-post assessment of diet and physical activity habits. The intervention consisted in a multidimensional lifestyle intervention with training sessions, workshops, tournaments and educative supports. Data analysis was stratified according to socioeconomic status.

Results

At baseline, 270 and 269 preschoolers composed respectively the intervention and control groups. At the post-assessment, the number increased to respectively 347 and 230 preschoolers in intervention and control groups. In the intervention group, 52.9% of the mothers and 56.5% of the fathers were executive versus 37.1% and 43.5% respectively in the control group. In the intervention group, the proportion of children with balanced eating habits had significantly increased between baseline and post-assessment for both executive parents. The proportion of preschoolers doing physical activity outdoors the kindergarten was improved among executive mothers and fathers in the intervention group without significant change. In the control group, there was an increase observed only for executive fathers.

Conclusion

Significant changes of physical activity habits and diet characteristics were obtained in the intervention group unlike the control group. The socioeconomic status seems to be determinant in guiding intervention program.

Key words

health promotion, lifestyle change, obesity, pediatrics, physical activity, prevention

Introduction

The high prevalence of childhood obesity and sedentary represents a major public health burden [1]. Worldwide, over 42 million children under 5 years are overweight [2]. In Tunisia, the data on childhood obesity are still not widely available. In Tunis, the overall prevalence of overweight and obesity in a cohort of 1335 school children were respectively 19.7% and 5.7% [3]. Another survey of 100 preschool children showed 46% the proportion of children with overweight [4]. On the other hand, American studies noted that 60% of children under five years spend their time playing outside in sedentary activities [5]. In Tunisian studies, the evaluation of food practice showed many failures, exposing children to obesity, related to caloric food [6] and about 91% of toddlers have no physical activity outside of kindergarten [4]. These results of childhood obesity and physical inactivity are worrisome [7], and highlight the urgent need for preventive actions earlier in childhood.

Differences in the prevalence of childhood overweight across socio-economic status groups are likely to be explained by differences in characteristics of the children and their parents related to material circumstances, behavior and knowledge, all of which influence energy balance [6,8]. Therefore, understanding the influence of socio-economic status on patterns of eating and physical activity that lead to early childhood obesity is critical for the development of effective prevention programs [9].

Little research has been devoted to preschool obesityprevention in Tunisia, and results of the studies remain controversial. To our knowledge, this study represents the first one investigating kindergarten-based lifestyles intervention in Tunisia, and one of the few studies conducted in developing countries too.

The purpose was to evaluate feasibility and effects of an intervention program for preschoolers, parents and kindergarten staffs aiming to increase the proportion of children doing physical activity and those with balanced eating habits.

Methods

Study design

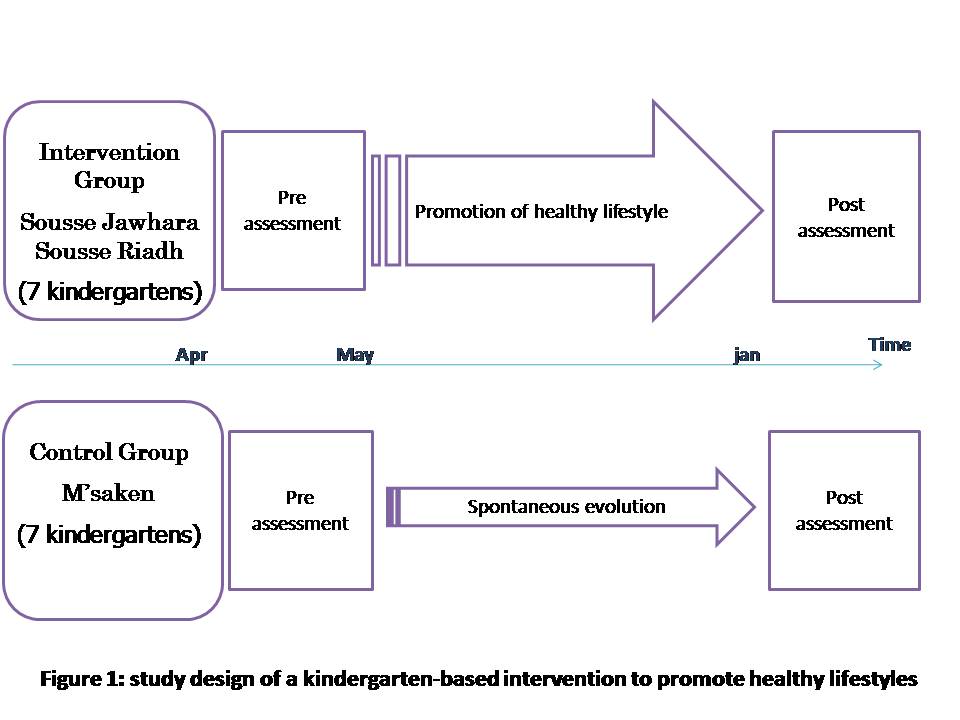

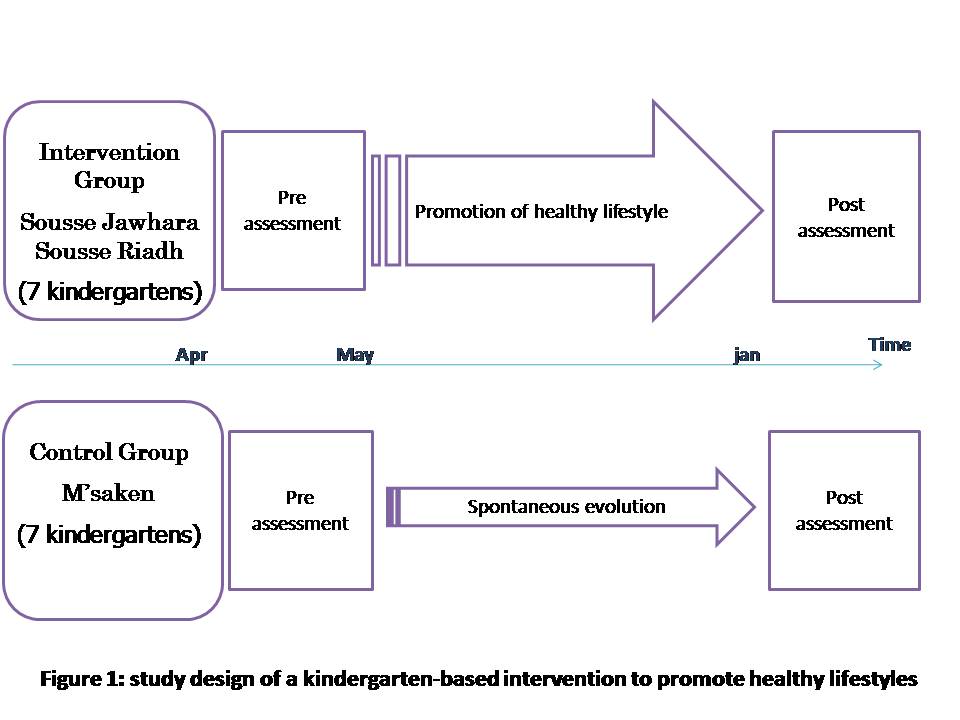

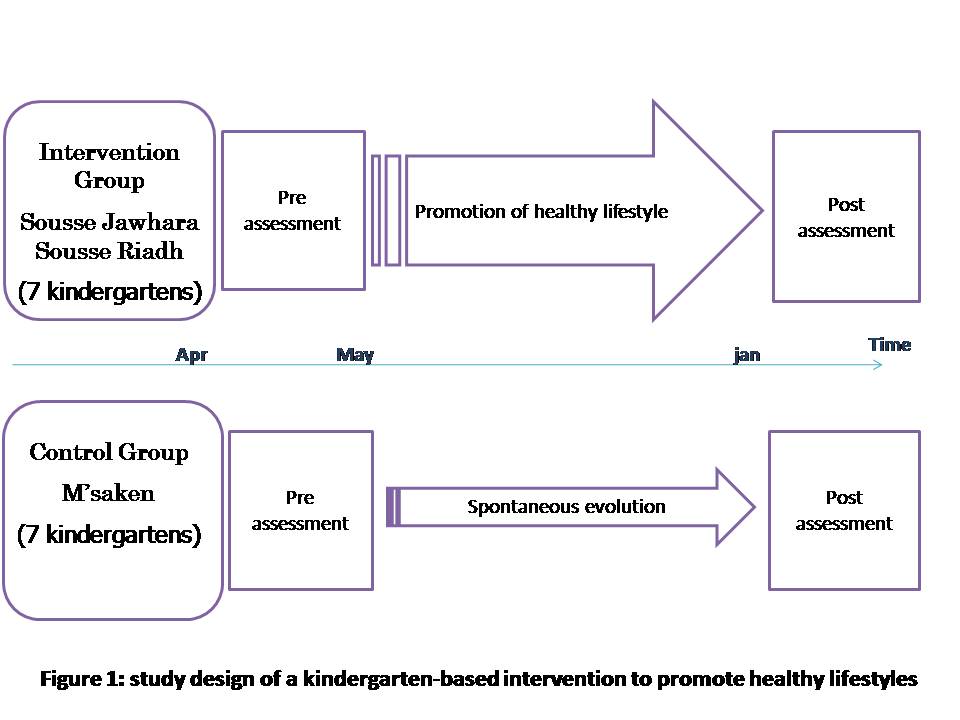

We carried out a quasi experimental intervention study with two groups: a control group and an intervention group. Two delegations of the region of Sousse, Tunisia (Jawhara-Riadh and M'saken) were chosen to form respectively the intervention group and the control group. This choice was guided by reasons of feasibility and accessibility (convenience). Figure 1 presents the diagram in time of the study design. The study started in March 2013 and ended in January 2014. The intervention program lasted for 8 months (April 2013- November 2013).

Figure 1. Study design of a kindergarten-based intervention to promote healthy lifestyles

Study population

Our population was composed of children aged 4 to 5 years enrolled in kindergartens, their parents and the kindergarten staff.

The sample size was based on a significance level of α = 5% and a power 1- β= 80% and 10% change in physical activity practice and balanced eating habits. So, we have needed 208 children in each group to achieve the aim of the study. However, as children could move from a kindergarten to another, we have increased this number (=208) by 20% to take into account the non-respondents. Then, the required sample size was 250 children in each group and therefore, we have needed 7 kindergartens (with more than 35 children by kindergarten) in each group.

A proportional sampling was used. In fact, the 14 kindergartens were matched based on the number of the children enrolled in each kindergarten. Only kindergartens with more than 35 preschoolers were selected for inclusion. Random samples of 7 kindergartens have been selected in each group.

Intervention program

Many meetings with local policy makers (Regional Department of Childhood of Sousse) were made to determine the existent kindergartens conditions concerning physical activities and eating habits. The ability of conducting a scientific work in such settingsand the specificities of the intervention program was also explored with kindergartens inspectors, headmistresses and teachers.

Different actions for the promotion of healthy lifestyles were scheduled during the intervention phase which lasted 8 months:

* A training session for kindergartens staffs was animated by a pediatrician and a dietician with the theme «How to prevent unhealthy diet and physical inactivity in preschool children?

*Another training session was made by a psychologist for kindergartens staffs on how to deal with child in preschool setting.

*A workshop with headmistress aimed the establishment of good practices to promote healthy eating in kindergartens (provide a fixed schedule for the afternoon snack and ensure the elimination of the morning snack, promote healthy snacks composed by fruit and / or vegetables, discourage high calorie snacks such as candy, chocolate and chips, and avoid using food as a reward or punishment).

*An educational support was elaborated and provided to kindergartens teachers with standard information on diet and physical activity which served for the learning activities.

On the other hand, several actions were also organized for preschoolers 'parents:

*a workshop on healthy eating animated by dietician

*a cooking workshop in kindergarten for parents and children on how to prepare healthy snacks together.

*a workshop animated by a physical activity professional for parents and children taking place at the kindergarten aiming improvement of their physical activity habits.

* Different awareness messages on the promotion of healthy eating and physical activity was sent each week to parents through the workbook of the child, and then by SMS during summer holidays.

Data collection

We have used 2 types of pre-tested questionnaires:

- A self-administered questionnaire for parents to get information on parents feeding style, their children’s lifestyle and socio-demographic characteristics. The topic covered by the questionnaire were; Family eating style, child’s food preferences and physical activity habits, child’s TV use, parents social economical level, age and sex.

- A questionnaire for children includedas an exercise in learning activities, based on selecting pictures of healthy/liked food and healthy/liked physical activity.

Children and their parents have been assessed at pre and post intervention. The post assessment was done at the end of the intervention.

The study started in March 2013 and ended in January 2014. The intervention program lasted for 8 months (April 2013- November 2013).

Data collection has been done by the project trained medical doctor. Data have been collected and treated in the department of Epidemiology anonymously.

Balanced eating habit was defined as consumption of 3 main meals with a healthy snack in the afternoon.

Data management plan

We have used SPSS 10.0 Software for data capture and analysis.

We compared for both the intervention and control group, before and after the intervention the level of physical activity, the rhythm of meals per day and its components.

For the description of categorical and continuous variables we calculated percentages and means respectively at each assessment and examined the differences using respectively analyses of Chi-square statistics and test-t.

Ethical consideration

The study protocol was submitted to the Ethical Committee of the University Hospital Farhat Hached for approval which was obtained. We have got the parents informed written consent before the enrollment of their children in the study. In both intervention and control groups, the participants parents were informed about the aim of the study and its progress. Only children whose parents have consented to participate to data collection and intervention have been included in the study. Our intervention consisted on health education and promotion of healthy lifestyle so it didn’t present any harm for participating children.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the preschoolers and their parents in the intervention and control groups

At baseline, the intervention group was composed of 270 preschoolers and the control group of 269 preschoolers. At the post-assessment, they became respectively 347 and 230 preschoolers.

Concerning sex, 53.6% of the children in the intervention group were boys versus 46.4% in the control group and there was no significant difference between the two groups at baseline (p=0.09). The mean age in the intervention and control group were respectively 4.50 years (± 0.51) and 4.73 years (± 0.34); (p<10-3).

From the parental characteristics, we have considered the employment status of both mother and father. This variable was transformed in two categories (executive or housewife/worker for the mother, executive or worker for the father) which allowed meaningful comparisons between these subgroups of the different employment status.

In the intervention group, 52.9% of the mothers were executive versus 37.1% in the control group (p<10-3).

In the control group, 56.5% of the fathers were executive versus 43.5% in the control group (p=0.014).

Preschoolers knowledge’s concerning healthy food and beneficial physical activity

Children knowledge’s were evaluated through their choice of pictures from 2 lists, each one composed of 14 pictures representing healthy food or beneficial physical activity.

The preschoolers’ knowledge's concerning healthy food was illustrated through the mean number of healthy food identified. For the intervention group, it was 5.51 ± 3.29 at baseline versus 7.06 ± 3.37 at the post assessment (p<10-3). For the control group, it was 5.76 ± 3.10 at baseline versus 6.36 ± 3.58 at the post assessment (p=0.04).

The preschoolers’ knowledge's concerning physical activity was illustrated through the mean number of beneficial activity identified. For the intervention group, it was 2.68 ± 1.13 at baseline versus 3.20 ± 1.61 at post assessment (p<10-3). For the control group, it was 3.20 ± 1.32 at baseline versus 3.16 ± 1.30 at post assessment (p=0.73).

Lifestyles-related characteristics of the preschoolers in the intervention and control group

To assess the diet, we have asked parents information on the number of meals, the composition of the snacks and the nibbling.

Concerning eating habits (Table 1), the increase of the proportion of participants with balanced eating habits between baseline and post-assessment was obtained for almost all participants. However, it was only significantin the intervention group for executive parental statuses (19.6% versus 31.1%, p<0.05 for children of executivemothers and 17.8% versus 31.1%, p<0.05 for children of executive fathers). In the control group and for the same subgroup, the increase was also obtained but wasn’t significant (12.2% versus 15.5%, p=0.59 for children of executivemothers and 10.7% versus 15.1%, p=0.36 for children of executive fathers).

Table 1. Preschoolers' eating habits as reported by their parents in the intervention and control groups at baseline and post-assessment

|

|

Intervention group

|

Control group

|

|

|

Baseline %(n)

|

Post- assessment %(n)

|

p

|

Baseline %(n)

|

Post- assessment %(n)

|

p

|

|

Nibbling

|

|

Mother employment:

|

|

Executive

|

75.4 (105)

|

61.5 (99)

|

0.01

|

85.7 (84)

|

74.1 (43)

|

0.08

|

|

Housewife/ worker

|

78.7 (97)

|

71.8 (130)

|

0.17

|

83.5 (137)

|

74.7 (109)

|

0.04

|

|

Father employment:

|

|

Executive

|

76.3 (116)

|

63.3 (112)

|

0.01

|

86.1 (106)

|

76.7 (66)

|

0.08

|

|

Worker

|

79.3 (92)

|

70.4 (114)

|

0.09

|

83.5 (100)

|

72.9 (86)

|

0.05

|

|

Balanced eating habit (3 main meals with a healthy snack in the afternoon)

|

|

Mother employment:

|

|

Executive

|

19.6 (28)

|

31.1 (50)

|

0.002

|

12.2 (120)

|

15.5 (9)

|

0.59

|

|

Housewife/ worker

|

13.9 (17)

|

21.5 (39)

|

0.09

|

7.9 (13)

|

15.1 (22)

|

0.05

|

|

Father employment:

|

|

Executive

|

17.8 (28)

|

31.1 (55)

|

0.007

|

10.7 (14)

|

15.1 (13)

|

0.36

|

|

Worker

|

14.7 (18)

|

21 (34)

|

0.19

|

8.3 (12)

|

15.3 (18)

|

0.01

|

Likely, the decline of the nibbling demonstrated between baseline and post intervention was significant for the subgroups corresponding to executive parental statuses in the intervention group (75.4%versus 61.5, p=0.01 for children of executive mothers; 76.3% versus 63.3%, p= 0.01 for children of executive fathers), but not in the control group (85.7% versus 74.1%, p=0.08 for children of executive mothers; 86.7% versus 76.7%, p=0.08 for children of executive fathers).

Concerning physical activity data (Table 2), the categories are indicated below in parentheses. Parents have precised how their children go to kindergarten (walking or taking a mean of transport), if their children play outdoors (yes/no), how much time they spent doing it (<1 h/ day,>1 h/day) and how much time their children spent watching TV per day (>2 h/day, <2 h/day).

The proportion of preschoolers doing physical activity outdoors the kindergarten was improved for the whole among executive mothers and fathers in the intervention group without significant change. In the control group, there was an increase observed only for executive fathers.

Table 2. Preschoolers' physical activity habits as reported by their parents in the intervention and control groups at baseline and post-assessment

|

|

Intervention group

|

Control group

|

|

|

Baseline %(n)

|

Post- assessment %(n)

|

p

|

Baseline %(n)

|

Post- assessment %(n)

|

p

|

|

Practice of physical activity outdoors the kindergarten

Mother employment:

|

|

Executive

|

70.4 (96)

|

76.1 (121)

|

0.28

|

66.3 (65)

|

58.6 (34)

|

0.37

|

|

Housewife/ worker

|

75.4 (92)

|

71.9 (128)

|

0.51

|

64.4 (105)

|

65.3 (94)

|

0.87

|

|

Father employment :

|

|

Executive

|

69.3 (104)

|

75.3 (131)

|

0.22

|

62.6 (77)

|

68.6 (59)

|

0.35

|

|

Worker

|

76.5 (88)

|

72.5 (116)

|

0.43

|

66.9 (95)

|

58.6 (68)

|

0.17

|

|

Spend less than 2 hours per day in screen viewing

|

|

Mother employment:

|

|

Executive

|

75.4 (102)

|

89 (138)

|

0.002

|

70.8 (68)

|

69.1 (38)

|

0.9

|

|

Housewife/ worker

|

79.2 (10)

|

90.7 (156)

|

0.005

|

67.1 (109)

|

75.2 (106)

|

0.11

|

|

Father employment:

|

|

Executive

|

71.6 (106)

|

89.3 (151)

|

<10-3

|

66.9 (63)

|

70.7 (58)

|

0.5

|

|

Worker

|

83.2 (95)

|

90.3 (140)

|

0.09

|

70.3 (98)

|

75.4 (96)

|

0.35

|

|

Going to the kindergarten on foot

|

|

Mother employment:

|

|

Executive

|

22.8 (32)

|

24.5 (39)

|

0.72

|

52.1 (51)

|

39.7 (23)

|

0.09

|

|

Housewife/ worker

|

49.6 (61)

|

42.7 (76)

|

0.22

|

74.2 (120)

|

76.2 (109)

|

0.69

|

|

Father employment:

|

|

Executive

|

28.0 (32)

|

32.6 (57)

|

0.41

|

56.2 (68)

|

53.5 (46)

|

0.75

|

|

Worker

|

43.9 (51)

|

35.2 (56)

|

0.15

|

75.4 (108)

|

73.9 (85)

|

0.76

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Concerning, sedentary time spent in front of television or videogames, we have note that more preschoolers spent less than 2 h/day in the intervention group than in control group for the whole parental employment subgroups. In the intervention group significant improvement was observed among the children of executive mothers and fathers but also for worker mothers. Unlike the control group where there was no significant difference.

In the intervention group, the proportion of preschoolers going to kindergarten on foot was improved independently of the parents’ employment status but there was no significant difference. In the control group only children of worker mothers improved this habit without significant changes.

Parents’attitudes regarding their children's lifestyles

There was increase of positive attitudes among parents in the intervention group. The increase of the proportion of parents preparing frying food never or maximum once a week was significant only among children of executive mothers and fathers (Table 3). However, parents in the control group (in all subgroups) were more likely to participate in doing physical activity with their children.

Table 3. Parents' attitudes regarding their children's lifestyles in the intervention and control group at baseline and post-assessment

|

|

Intervention group

|

Control group

|

|

|

Baseline %(n)

|

Post- assessment %(n)

|

p

|

Baseline %(n)

|

Post- assessment %(n)

|

p

|

|

Prepare frying food never or maximum once a week

|

|

Mother employment:

|

|

Executive

|

82.6 (114)

|

92.5 (148)

|

0.01

|

85.6 (84)

|

86 (49)

|

0.87

|

|

Housewife/ worker

|

87.6 (106)

|

86.9 (92)

|

0.8

|

81.9 (132)

|

79.9 (115)

|

0.66

|

|

Father employment:

|

|

Executive

|

84.9 (130)

|

92 (161)

|

0.04

|

88.5 (108)

|

85.8 (73)

|

0.63

|

|

Worker

|

84.4 (98)

|

87.6 (141)

|

0.41

|

78.4 (109)

|

78.5 (91)

|

0.91

|

|

Participate in doing physical activity with their children

|

|

Mother employment:

|

|

Executive

|

38.3 (51)

|

36.5 (50)

|

0.71

|

25.0 (24)

|

32.2 (13)

|

0.88

|

|

Housewife/ worker

|

38.5 (44)

|

33.5 (60)

|

0.37

|

27.2 (45)

|

29.2 (40)

|

0.65

|

|

Father employment:

|

|

Executive

|

38.9 (58)

|

39.2 (69)

|

0.93

|

29.8 (37)

|

28.9 (24)

|

0.87

|

|

Worker

2021 Copyright OAT. All rights reserv

|

37.6 (40)

|

30.8 (49)

|

0.24

|

22.9 (33)

|

27.3 (30)

|

0.47

|

Figure 1. Study design of a kindergarten-based intervention to promote healthy lifestyles

Discussion

The objective of the present study was to establish a kindergarten-based program for preschoolers, their parents and teachers to increase the proportion of children doing physical activity and those with balanced eating habits. A quasi-experimental intervention study was carried out. Intervention effects were observed for participants of executive mothers and fathers. Indeed, for this subgroup, we found positive changes of the preschoolers’ habits and knowledge and their parents’ attitudes concerning healthy eating and physical activity practice. Thus, some limitations need to be taken into account while considering main outcomes. Overall, the parental self report assessment of lifestyle habits and the absence of an objective measurement of physical activity practice limit outcomes validity.

On the other hand, our study, in accordance with recent researches [10] highlight the need to focus on younger children to prevent obesity earlier, in a period where the basis for a healthy lifestyle is still being established and therefore it is easier to change these behaviors compared to adult populations [11]. Current evidence suggests that many diet and exercise interventions to prevent obesity in children are not effective in preventing weight gain, but can be effective in promoting healthy lifestyles [12]. In fact, they improve nutrition and physical activity knowledge and preferences, improve fitness, and decrease the percent of overweight children. Such interventions may play an important role in health promotion, prevention and treatment of childhood obesity [13].

A growing body of research recommend community-based approaches to prevent childhood obesity. In fact, multi-sector and multi-strategy interventions demonstrate great promise as being effective and also having the potential to be equitable, sustainable and cost-effective [10,14]. Parents and kindergarten teachers are important stakeholders in the lives of children [15]. They play key-roles in helping preschoolers to develop positive dietary behaviors [16,17], and to improve their physical activity level [14,18,19]. Therefore, preschools and other settings are recognized as determining settings for population-based obesity prevention efforts given their important role in promoting healthy eating and physical activity for children [18,19]. Based on this approach, we have developed a multi-component intervention program with innovative tools (i.e. .mobile SMS in holidays, cooking workshops at kindergarten), integrating ordinary activities (i.e. exercise, learning activities) and involvement of major interveners (parents, local stakeholders, kindergarten staff). Feasibility, acceptability and short-term effects on dietary and physical activity habits were successfully obtained, similarly to significant literature data [10].

The K-GFYL program, for example, including support and professional development for staff within kindergarten settings, demonstrate practice changes that promote healthy eating and physical activity for children and their families [14,20].

A Malaysian study found that even in so early age, children were able to know and differentiate between healthy foods and junk foods [21], due to the parents and teachers’ role. Another study conducted in number of German kindergarten settings noted that children can prepare ‘magic fruit plate’ twice weekly. Authors then recommended that health promotional activities should increase in preschool children in Germany [22]. The improvement of our preschoolers’ knowledge’s attested these conclusions.

Recent data from the literature revealed that maternal work hours for example are positively associated with childhood obesity especially among children with higher socioeconomic status [23]. However, some systematic review and meta-analytic literature on the management of obesity confirmed the absence of evidence regarding the efficacy of interventions targeting specific socio-economic, ethnic or vulnerable childhood groups [24,25]. This fact incited us to present our results with regard to the parental employment status. Comparing the effectiveness of our intervention on dietary and physical activity with others studies, our findings were potentially the desired expectations. We recommend therefore that socio-economic factors are determining in guiding further programs elaboration and establishment.

But, in view of the short-term and the sample size of the study, there was little contrast with an American home-based intervention, which demonstrated short-term effects on dietary and sedentary behaviors for low-income children [10]. Indeed, contradictory results of different studies can be a result of a small sample, difference in study design and different criteria for defining categories within investigated socioeconomic factor [26]. Further high-quality research is necessary so to enhance the current evidence base andoptimize outcomes [24].

This study demonstrated the feasibility of intervention program in kindergarten for healthy lifestyle promotion. It could be integrated in the curriculum of children in kindergarten to be sustained and generalized. However, it needs to be adapted to all categories of the population.

Conclusion

Significant changes of physical activity habits and diet characteristics were obtained in the intervention group unlike the control group. The socioeconomic status seems to be determinant in guiding intervention program.

Acknowledgments/Funding information

This manuscript was based on a project funded by United Health Group-NHLBI Chronic disease initiative (Trainee Awards).

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Puder JJ, Marques-Vidal P, Schindler C, Zahner L, Niederer I, et al. (2011) Effect of multidimensional lifestyle intervention on fitness and adiposity in predominantly migrant preschool children (Ballabeina): cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 343: d6195. [Crossref]

- World Health Organization. Childhood overweight and obesity.

- Boukthir S, Essaddam L, Mazigh Mrad S, Ben Hassine L, Gannouni S, et al. (2011) Prevalence and risk factors of overweight and obesity in elementary schoolchildren in the metropolitan region of Tunis, Tunisia. Tunis Med 89: 50-54. [Crossref]

- Belabed Chalgoum N, Abdelkafi Koubaa A, Dahmen H, Kochbati A (2009) Nutritional practices of young children. Tunis Med 87: 786-789. [Crossref]

- Dakhli S, Ben Ammar I, Zouaoui C, Hmida C, Ben Mami Ben Miled F, et al. (2008) Analyse des facteurs de risque de l’obésité infantile dans un groupe d’enfants des écoles maternelles de la région de Tunis. Diabetes Metab 34: A40-A100.

- Brown WH, Pfeiffer KA, McIver KL, Dowda M, Addy CL, et al. (2009) Social and environmental factors associated with preschoolers' nonsedentary physical activity. Child Dev 80: 45-58. [Crossref]

- VanVrancken-Tompkins CL, Sothern MS (2006) Prévention de l’obésité chez les enfants de la naissance à cinq ans. In: Tremblay RE, Barr RG, Peters RDeV, eds. Encyclopédie sur le développement des jeunes enfants [sur Internet]. Montréal, Québec: Centre d’excellence pour le développement des jeunes enfants; 1-7.

- Shrewsbury V, Wardle J (2008) Socioeconomic status and adiposity in childhood: a systematic review of cross-sectional studies 1990-2005. Obesity (Silver Spring) 16: 275-284. [Crossref]

- Veldhuis L, Vogel I, van Rossem L, Renders CM, Hirasing RA, et al. (2013) Influence of maternal and child lifestyle-related characteristics on the socioeconomic inequality in overweight and obesity among 5-year-old children; the "Be Active, Eat Right" Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 10: 2336-2347. [Crossref]

- Keita AD, Risica PM, Drenner KL, Adams I, Gorham G, et al. (2014) Feasibility and acceptability of an early childhood obesity prevention intervention: results from the healthy homes, healthy families pilot study. J Obes 2014: 378501. [Crossref]

- O'Dwyer MV, Fairclough SJ, Knowles Z, Stratton G (2012) Effect of a family focused active play intervention on sedentary time and physical activity in preschool children. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 9: 117. [Crossref]

- Askie LM, Baur LA, Campbell K, Daniels LA, Hesketh K, et al. (2010) The Early Prevention of Obesity in Children (EPOCH) Collaboration--an individual patient data prospective meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 10: 728. [Crossref]

- Nemet D, Geva D, Eliakim A (2011) Health promotion intervention in low socioeconomic kindergarten children. J Pediatr 158: 796-801. [Crossref]

- de Silva-Sanigorski A, Prosser L, Carpenter L, Honisett S, Gibbs L, et al. (2010) Evaluation of the childhood obesity prevention program Kids--'Go for your life'. BMC Public Health 10: 288. [Crossref]

- Hu C, Ye D, Li Y, Huang Y, Li L, et al. (2010) Evaluation of a kindergarten-based nutrition education intervention for pre-school children in China. Public Health Nutr 13: 253-260. [Crossref]

- Longbottom PJ, Wrieden WL, Pine CM (2002) Is there a relationship between the food intakes of Scottish 5(1/2)-8(1/2)-year-olds and those of their mothers? J Hum Nutr Diet 15: 271-279. [Crossref]

- Hart KH, Herriot A, Bishop JA, Truby H (2003) Promoting healthy diet and exercise patterns amongst primary school children: a qualitative investigation of parental perspectives. J Hum Nutr Diet 16: 89-96. [Crossref]

- Gill TP, Baur LA, Bauman AE, Steinbeck KS, Storlien LH, et al. (2009) Childhood obesity in Australia remains a widespread health concern that warrants population-wide prevention programs. Med J Aust 190:146-148. [Crossref]

- Rogers E, Moon AM, Mullee MA, Speller VM, Roderick PJ (1998) Developing the 'health-promoting school'--a national survey of healthy schools awards. Public Health 112: 37-40. [Crossref]

- Honisett S, Woolcock S, Porter C, Hughes I (2009) Developing an award program for children's settings to support healthy eating and physical activity and reduce the risk of overweight and obesity. BMC Public Health 9: 345. [Crossref]

- Alattraqchi AG, Binti Abu Bakar M, Binti Abu Bakar Mohamad A, Binti Abdul Kadir A, Binti Mohd Yahya N, et al. (2014) Awareness of Tadika’s (Kindergarten) Children towards Healthy Lifestyle in Kuala Terengganu, Malaysia. J App Pharm Sci 4: 115-122.

- Herbert B, Strauß A, Mayer A, Duvinage K, Mitschek C, et al. (2012) Implementation process and acceptance of a setting based prevention programme to promote healthy lifestyle in preschool children. Health Education Journal 72: 363-372.

- Datar A, Nicosia N, Shier V (2014) Maternal work and children's diet, activity, and obesity. Soc Sci Med 107: 196-204. [Crossref]

- Ells LJ, Campbell K, Lidstone J, Kelly S, Lang R, et al. (2005) Prevention of childhood obesity. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 19: 441-454. [Crossref]

- Mulvihill C, Quigley R (2003) The Management of Obesity and Overweight: Analysis of Reviews of Diet Physical Activity and Behavioural Approaches. (1stedn), London: Health Development Agency.

- Bilic-Kirin V, Gmajnic R, Burazin J, Milicic V, Buljan V, et al. (2014) Association between socioeconomic status and obesity in children. Coll Antropol 38: 553-558. [Crossref]