Abstract

Acute complete closure of inferior vena cava is a dreadful complication. Here, we present a case with iatrogenic complete closure of the inferior vena cava treated with Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy (CRRT) device. A 68 years old male patient, presented with an abdominal aortic aneurysm of 8 cm. He underwent abdominal aneurysm repair. During the operation, the inferior vena cava was accidentally perforated. It was technically impossible for the surgical team to repair the perforation, so it was ligated in order to stop the bleeding. Complete obstruction of the venous flow found our patient's collateral veins unpre- pared, and therefore unable to perform adequate drainage of the blood from the lower extremities, resulting in inadequate preload and the following hypovolemic shock. We found a practical, off-protocol CRRT solution to this critical case in first the hours in ICU. We inserted central venous catheters in left femoral vein (inflow) and left subclavian vein access(outflow). The CRRT device was connected to the patient with a flow of 150-200 ml/min. The patient found hemodynamic stability and the kidney began to function with a diuresis of 80-100 ml/h. There was no metabolic acidosis, the patient needed less support with crystalloid solution, albumin and blood transfusion. The ultrafiltration was discontinued 48 hours later and the patient left the intensive care unit 72 hours from surgery. We found CRRT device with 200 ml/min flow a very good temporary solution of this deadly complication and we believe that can be employed in other similar cases.

Key words

Inferior Vena Cava IVC; CRRT Device; Skunt; IVC Acute Closure

Introduction

Major venous injury during abdominal aortic reconstruction, though uncommon, often result in sudden and massive blood loss resulting in increased morbidity and mortality. This case report details the aetiology, management, and outcome of such injuries.

Case Report

A 68 years old male patient, 85 kg, ASA 3 (The American Society of Anesthesiolo-gists) classification, presented with an abdominal aortic aneurysm of 8 cm. He underwent open surgery for abdominal aneurysm repair.

The patient was monitored invasively for blood pressure and central venous pressure (CVP), and received general anaesthe- sia (pancuronium, propofol, fentayl, sevoflurane) combined with epidural anaesthesia (lidocaine 2%, Bupivacaine 0,5%). Heparin 5000 UI was used like an anticoagulant before aortic clamping.

During the operation, the inferior vena cava was accidentally perforated and we started immediately blood transfusion, fresh frozen plasma, colloid solution, to save the circulating volume. The cell saver was also used to aspirate the blood. Given the emergency of this life-threatening condition, it was impossible for the surgical team to stich the perforation and correct the complication by repairing the defect. The inferior vena cava was ligated below the renal veins in order to stop the bleeding.

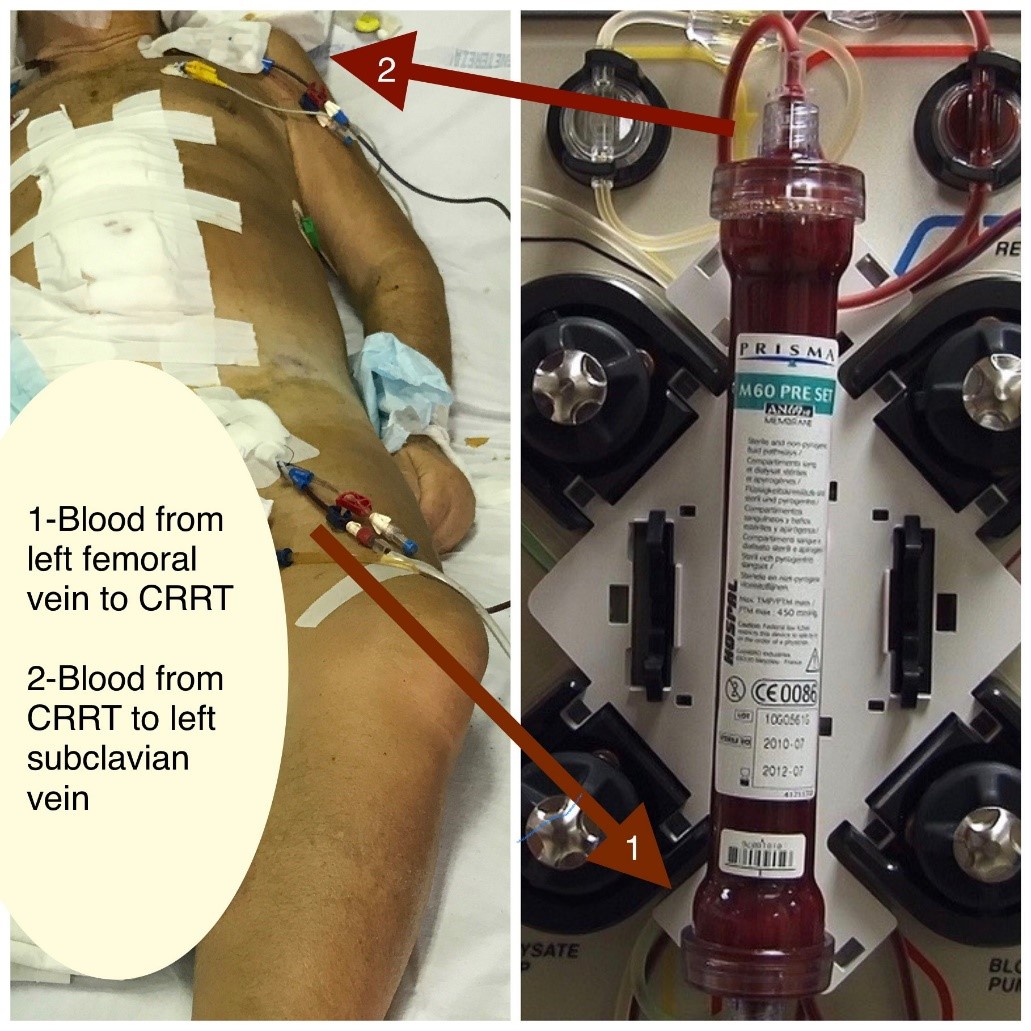

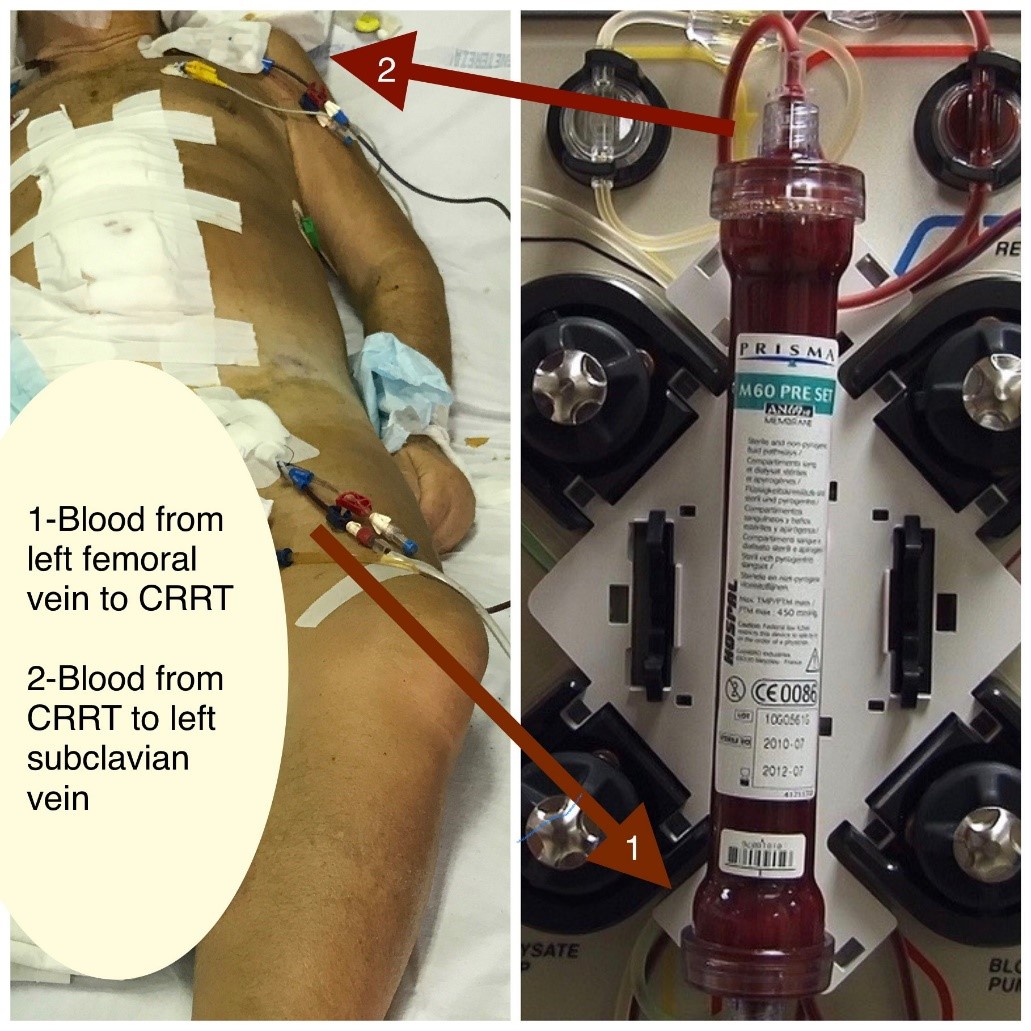

After the vena cava ligature the haemorrhage was stopped but the hemodynamic situation was not stable and the patient needed continuous circulating volume. Complete obstruction of the venous flow found our patient's collateral veins unpre- Results Figure 1: Off-protocol CRRT shunt pared, and therefore unable to perform adequate drainage of the blood from the lower extremities, resulting in inadequate preload and the following hypovolemic shock.

Figure 1: Off-protocol CRRT shunt

Surgery lasted five hours and consisted in resection of the aneurysm and placement of an aortic-bifemoral Dacron graft 16/8. The patient was transferred in the intensive care unit with hemodynamic instability (AP 70/80-40 mmHg, FC 105-130 bpm, CVP 2 mmHg), metabolic acidosis, no diuresis and inferior legs oedema despite aggressive medical treatment.

We found a practical, off-protocol CRRT solution to this critical situation in first days in intensive care unit (ICU). We inserted central venous catheters in left femoral vein(inflow) and left subclavian vein access(outflow). The CRRT device was connected to the patient with a flow of 150-200 ml/min.

The pump was placed with max flow 200 ml/min. Heparin was started with 2000 UI bolus, and continued 500 UI /h. We decided this therapy because we thought that the collateral vein system was insufficient to drain the blood from inferior part of the body and to give this system the possibility to be adapted.

Results

The hemodynamic status started to stabilize immediately within the first hours with an arterial pressure (AP) of 95-100 mmHg, heart rate (HR) of 105 bpm, central venous pressure (CVP) 0-1 mmHg. The urine flow started with 0,5 ml/kg in the first hour stimulated with Lasix 10mg/h. The situation kept improving in the following hours. The day after surgery the patient was awake and intubated. The inferior legs were warm and oedematous. Heparin therapy with 15000 UI/d was used to maintain the assistance of CRRT-200-180-150 ml/min. The second day in ICU the patient was extubated remained with oxygen support via a nasal cannula. He continued the assistance of CRRT-150-120-100 ml/min. There were no abdominal problems during this period.

The third day the patient was in a good condition. We judged that the collateral vein system was adapted to afford the blood drainage from the inferior extremities. Considering that the filter had 48 hours of functioning, we decided to stop the CRRT assistance. On the fifth day after surgery the patient was in a stable condi- tion, good hemodynamic status and moderate leg oedema, so he left the intensive care unit.

Discussion

Documented cases of vena cava ligation are rare. The earliest reported inferior vena cava (IVC) ligations date back to Kocher in 1883 and Billroth in 1885. The first survivors of vena cava transection were reported by Bottini for infrarenal and Detrie for suprarenal ligation [1]. Ivy et al, described 23 case reports of infra-renal caval ligation and six case reports of suprarenal ligation in addition to their patient [2]. Trauma or intraabdominal tumour resection are the most frequent causes of IVC ligation [3,4]. Whereas infrarenal caval ligation has been performed more frequently, surgeons hesitate to ligate the suprarenal cava [5,6]. Hypotension and renal failure following ligation of an infrarenal cava occur immediately after the closure. Collateral circulation soon develops via the retroperitoneal and vertebral plexuses, ascending lumbar veins, and paraverte- bral veins, which drain into the azygos and hemiazygos systems. Testicular and ovarian veins may also contribute as accessory pathways.

The left renal vein and collaterals are the principal draining channels following suprarenal ligation of the IVC. The left adrenal vein and left spermatic/ovarian vein normally join the left renal vein. In addition, the left renal vein has lumbar and hemiazygos connections in 70% of patients [7]. Lumbar, ascending lumbar, and vertebral veins also contribute to collateral drainage.

In 35% of the patients, transient oedema of the extremities develops, which becomes permanent in 2% of patients [8]. Our patient had oedema of both lower limbs lasting one month. Transient defects in renal function manifesting as oliguria/anuria and haematuria with rising creatinine levels have also been observed following caval ligation [9,10]. Mortality varies with the level of IVC injury. Trauma to the infrarenal cava is associated with a mortality of 25%, whereas injuries between the renal and hepatic veins carry a mortality of 41–55%. The mortality rates for caval injuries at or above the level of the hepatic veins exceed 80% [2].

Mortality following IVC injury is attributed to persistent haemorrhage and associated hypotension, hypothermia, coagulopathy, and acidosis. Navsaria et al, retrospectively evaluated risk factors by comparing survivors and non-survi- vors after IVC injuries. They found that the site of injury and type of surgical management (ligation vs. repair) were not predictors of survival [4]. Thus, it may be concluded that the mortality associated with IVC injuries is related to the associat- ed trauma and surrounding organ injury. Elective ligation in a controlled setting allows collaterals to develop and results in a good outcome. When IVC ligation is performed, intensive monitoring to correct hypovolemic shock and possible abdominal compartment syndrome is required, particularly when the ligation is performed in the acute setting. In the context of trauma, with caval injuries, ligation of the IVC has been suggested as an acceptable and life-saving option [11].

We suggest the CRRT ultrafiltration in order to give time to the collateral circulation to adapt and also to support the kidney in this critical situation. We found no other reports of this off protocol treatment in the literature. In conclusion, management of IVC injury has long been a challenge. The key to management of IVC injury lies in the decision for repair or ligation. Repair should be given prefer- ence when possible. In an unavoidable circumstance, timely ligation of the IVC is rewarding and compatible with life.

Conclusion

We found CRRT device with 200 ml/min flow, a very good temporary solution of this deadly complication, to help the collateral vein system to be adapted to drain the blood from inferior part of the body. We believe that can be employed in other similar cases.

Consent

We have obtained informed consent for the publication of this case.

References

- Gazzaniga AB, Colodny AH (1972) Long- term survival after acute ligation of the vena cava above the renal veins. Ann Surg. 175: 563-8.

- Ivy ME, Possenti P, Atweh N, Sawyer M, Bryant G, Caushaj P (1998) Ligation of the suprarenal vena cava after a gunshot wound. J Trauma. 45: 630-2.

- Asensio JA, Chahwan S, Hanpeter D, Demetriades D, Forno W, Gambaro E, et al. (2000) Operative management and outcome of 302 abdominal vascular injuries. Am J Surg. 180: 528-34.

- Navsaria PH, de Bruyn P, Nicol AJ (2005) Penetrating abdominal vena cava injuries. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 30: 499-503.

- Cassebaum WH, Bukanz SL, Baum V, Azzi E (1967) Ligation of the inferior vena cava above the renal vein of a sole kidney with recovery. Am J Surg. 113: 667-70.

- Turpin I, State D, Schwartz A (1977) Injuries to the inferior vena cava and their management. Am J Surg. 134: 25-32.

- Anson BJ, Cauldwell EW, Pick JW, Beaton LE (1948) The anatomy of the para-renal system of veins, with comments on the renal arteries. J Urol. 60: 714-37.

- Timberlake GA, Kerstein MD (1995) Venous injury to repair or ligate, the dilemma revisited. Am Surg. 61: 139-45.

- Caplan BB, Halasz NA, Bloomer WE (1964) Resection and ligation of the suprarenal inferior vena cava. J Urol. 92: 25-9.

- Ramnath R, Walden EC, Caguin F (1966) Ligation of the suprarenal vena cava and right nephrectomy with complete recovery. Am J Surg. 112: 88-90.

- Kieffer E, Alaoui M, Piette JC, Cacoub P, Chiche L. Leiomyosarcoma of the inferior vena cava: experience in 22 cases. Ann Surg. 2006;244:289-295.