Aim: This meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) was performed to evaluate the effectiveness of probiotics in treating metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) in adult patients, focusing primarily on liver function, glucose levels, lipid metabolism, and inflammation.

Method: RCTs completed on or before November 30, 2024 were acquired from PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials databases. A meta-analysis of the therapeutic efficacy of probiotics on liver function, glucose and lipid metabolism, and inflammatory biomarkers was performed via RevMan 5.4 software. Two reviewers independently extracted studies and patient characteristics and evaluated the quality of the studies utilizing the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool. A meta-analysis was conducted using RevMan 5.4 software.

Results: A total of 18 RCTs involving 962 adult patients were included. According to the results of the meta-analysis, probiotic therapy may lower the levels of alanine aminotransferase [mean difference (MD): −9.09(−10.15, −8.03), p<0.00001], aspartate aminotransferase [MD: − 8.52(−9.48, −7.56), p<0.0001], glutamyl transferase [MD: −5.57(−6.68, −4.47), p<0.00001], total cholesterol [MD: − 0.17(−0.32, −0.02), p=0.03], fasting plasma glucose [MD: −0.47(−0.62, −0.33), p<0.00001], and homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance [MD: −0.65(−1.28, −0.03), p=0.04] in patients with MAFLD compared with those in control individuals. Nonetheless, among MAFLD patients, there was no statistically significant increase in triglyceride levels, tumor necrosis factor-α levels, or C-reactive protein levels.

Conclusion: There is promising evidence that probiotic supplementation can reduce liver enzyme levels and regulate glycometabolism and cholesterol metabolism in patients with MAFLD.

Keywords

probiotics, metabolic-associated fatty liver disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, gut microbiota, meta-analysis, randomized controlled trial, systematic review

Introduction

Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) (formerly non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)) is a condition characterized by the accumulation of fat in the liver, typically in the absence of excessive alcohol consumption. The term MAFLD refers to a range of liver conditions that include simple steatosis, steatosis with inflammation, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. MAFLD has become very common in the last few years and is now a major public health problem, which is strongly related to the increasing incidence of obesity, type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome. The prevalence of MAFLD is estimated to affect approximately 25% of the global population, with higher rates observed in individuals with metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes [1,2]. The pathophysiology of MAFLD is complex and involves multiple factors, such as dysregulation of lipid metabolism, insulin resistance, inflammation, and gut microbiota dysbiosis [3]. The gut microbiota has emerged as a critical player in the pathogenesis of MAFLD. Research indicates that gut dysbiosis, an imbalance in the gut microbial community, contributes significantly to the development and progression of MAFLD [4,5].

Probiotics are safe and beneficial in treating various gastrointestinal conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome, constipation, and hepatic encephalopathy [6-9]. Recent clinical trials and studies have demonstrated the efficacy of specific probiotic strains in improving liver function and reducing markers of liver inflammation in patients with MAFLD [10-12]. Given that multiple clinical trials have shown that probiotic supplementation has therapeutic effects on MAFLD, we conducted this meta-analysis of clinical RCTs to evaluate its efficacy, aiming to provide evidence-based guidance for the clinical treatment of MAFLD in adult patients.

Materials and methods

The reporting format of this systematic review was based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement revised in 2020 [13].

Registration of review protocol

The protocol for this review was registered in advance with PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews; CRD42025634671).

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria included the following: (1) studies on the treatment of adult patients with metabolic-associated fatty liver disease with probiotics; (2) randomized controlled trials, cluster randomized trials, and crossover trials; (3) placebo or standard treatment as the control group; (4) patients with metabolic-associated fatty liver disease; (5) outcomes, including survival events (mortality), clinical events, patient-reported outcomes (such as improvement in symptoms or quality of life), side effects, and other indicators; (6) studies using similar or comparable outcome measures; and (7) publications in English.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) studies not related to the treatment of metabolic-associated fatty liver disease with probiotics; (2) nonrandomized controlled trials; (3) studies without placebo or standard treatment as the control group; (4) patients who were under 18 years old; (5) patients with other liver diseases; (6) studies without clear outcome measures; (7) studies published in languages other than English; and (8) studies without full texts available.

Information sources

We conducted a comprehensive literature search of the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) from their inception to November 30, 2024. Only studies published in English were included.

Search strategy

((Probiotics OR probiotics supplement) AND ((Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease) OR (MAFLD) OR (Metabolic Dysregulation-Associated Fatty Liver Disease) OR (Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease) OR (NAFLD)))

Study selection

Two independent reviewers (Guo JT and Xu L) used a predefined relevance criterion form to screen the studies. After the titles and abstracts were read, duplicate studies and studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. Full-text access to relevant literature was obtained, and studies were screened for inclusion. Discrepancies at any stage were resolved by discussion with a third reviewer (Bai X). The level of agreement during screening was evaluated using the kappa statistic, with an a priori threshold of 0.60 for an acceptable level of agreement.

Data extraction

The data were extracted after the full texts were read. Two independent reviewers (Guo JT and Xu L) extracted the data. A third independent reviewer (Bai X) reviewed the data and resolved any discrepancies.

Data information

The extracted data included the following information: authors and publication year; study population; case number; treatment duration; intervention; and outcomes, such as alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), fasting blood glucose (FBG), homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-a), and C-reactive protein (CRP).

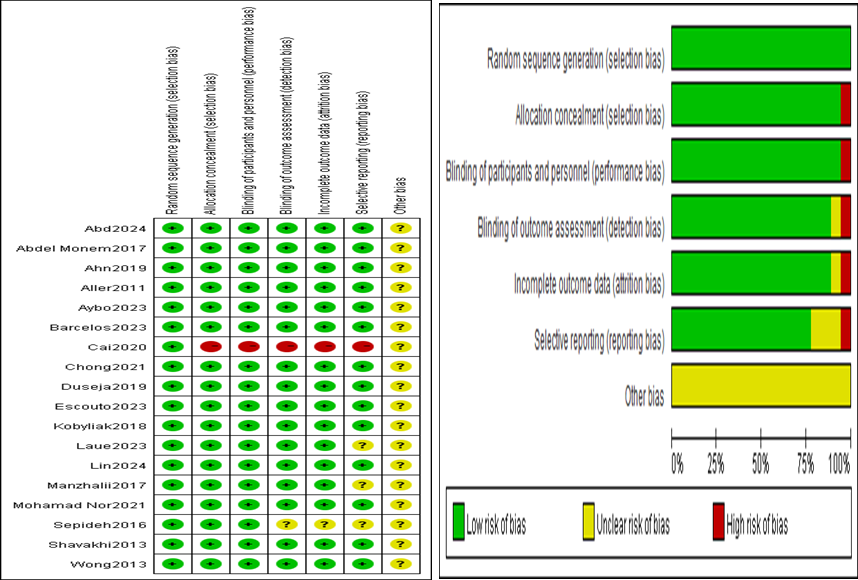

Risk of bias in individual studies

Risks of bias in individual studies were assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool. This tool assesses the following six domains of bias: sequence generation (decided as low risk bias, high risk, or unclear risk), allocation concealment (decided as low risk bias, high risk, or unclear risk), blinding of outcome assessment (decided as low risk bias, high risk, or unclear risk), incomplete outcome data (decided as low risk bias, high risk, or unclear risk), selective outcome reporting (decided as low risk bias, high risk, or unclear risk), and other types of bias (decided as low risk bias, high risk, or unclear risk). Two reviewers (Guo JT and Xu L) independently assessed study quality, and the assessments were verified by a third reviewer (Bai X).

Summary measures

For dichotomous data, summary statistics are expressed as odd ratios with 95% CIs for interpretation.

Synthesis of results

All analyses were conducted in Review Manager Version 5.4. A statistically significant difference was considered at α=0.05. Statistical heterogeneity in the included studies was examined using I2 statistics. If the result of the heterogeneity test was P>=0.10, a fixed effect model was used for the meta-analysis; if P<0.10, the sources of heterogeneity were investigated. If no obvious clinical heterogeneity and no clear statistical heterogeneity was observed, a random effects model was used for the meta-analysis. If the degree of clinical heterogeneity was too high, the data synthesis was discontinued, and a single research analysis was used instead. Sensitivity analysis was performed on some of the results from the aggregate analysis.

Assessment of publication bias

Potential publication bias was evaluated by funnel plot analysis.

Results

Study selection

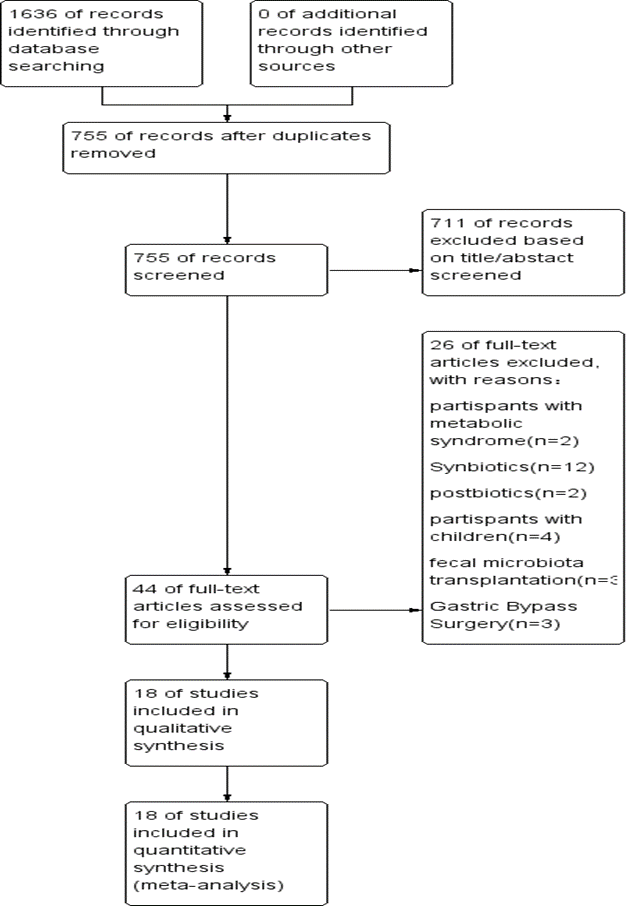

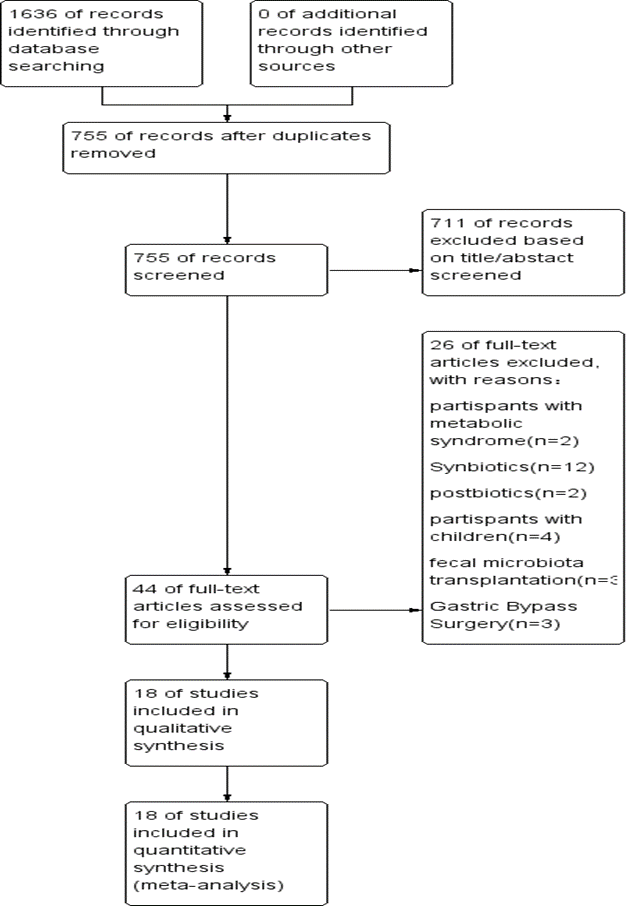

A total of 1636 English-language publications were identified in the literature search. Of the identified publications, 881 articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria were eliminated. After the titles and abstracts were read, 711 articles were eliminated. Forty-four full-text articles published in English were retrieved. Of these, 12 articles were excluded because the interventions involved synbiotics, 2 because the interventions involved postbiotics, 3 because the interventions involved gastric bypass surgery, 3 because the interventions involved fecal microbiota transplantation, 4 because the participants were children, and 2 because the participants had metabolic syndrome. Ultimately, 18 RCTs fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Figure 1 shows the flow chart of the retrieved studies. The level of agreement between the 2 reviewers was acceptable (κ = 0.67).

Figure 1. Flow chart of the retrieved studies

Study characteristics

The screening process is illustrated in a flow chart (Figure 1). From electronic and manual searches of the three databases, we obtained 1,636 trials, 881 of which were duplicates. Among the 755 unduplicated articles, 711 were excluded on the basis of their title or abstract, leaving 44 reports for full manuscript review. Only 18 RCTs met our inclusion criteria [10-12,14-28]. The summarized characteristics of the 18 RCTs are shown in Table 1. The total number of patients was randomized into probiotic and control groups. Most of the studies were randomized, parallel-group, placebo-controlled trials. Additionally, many of the clinical trials were double-blind trials. The 18 trials were published in English between 2011 and 2024, with sample sizes ranging from 20 to 140.

Studies |

Country |

n |

Intervention duration |

Interventions (Probiotic strain(s)) |

Interventions (control group) |

Outcomes |

Aller 2011 [14] |

Spain |

14/14 |

12 w |

Lactobacillus, Streptococcus |

Placebo |

HOMA-IR, TC, TG, ALT, AST |

Wong 2013 [15] |

Hong Kong |

10/10 |

180 d |

Lepicol probiotic |

Nonplacebo |

ALT, AST, BMI, IHTG, |

Shavakhi 2013 [28] |

Iran |

31/32 |

180 d |

Protexin |

Placebo |

ALT, AST, TC, TG, FBG |

Sepideh 2016 [25] |

Iran |

21/21 |

8 w |

Lactocare |

Placebo |

FBG, insulin, HOMA-IR, IL-6 |

Abdel Monem 2017 [17] |

Egypt |

15/15 |

4 w |

Lactobacillus |

Nonplacebo |

ALT, AST |

Manzhalii 2017 [18] |

Ukraine |

38/37 |

12 w |

Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Streptococcus |

Nonplacebo |

ALT, AST, GGT, TC, TG |

Kobyliak 2018 [19] |

Ukraine |

30/28 |

8 w |

Multi strain probiotics |

Placebo |

FLI, liver stiffness, ALT, AST, GGT, TC, TG, TNF-α, IL-6 |

Ahn 2019 [20] |

Korea |

30/35 |

12 w |

6 bacterial species |

Placebo |

IHF fraction, VFA, BMI, ALT, AST, TG, Insulin, IL-6, TNF-a, LPS, HOMA-IR |

Duseja 2019 [21] |

India |

19/20 |

48 w |

Multi strain probiotics |

Placebo |

ALT, AST, IL-6, TNF-a, Leptin, NAS score |

Chong 2021 [22] |

UK |

19/16 |

10 w |

Streptococcus, Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus |

Placebo |

ALT, AST, TC, TG, LDL-c, HOMA-IR, CRP,NAFLD fibrosis risk score |

Cai 2020 [26] |

China |

70/70 |

12 w |

Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus and Enterococcus |

Placebo |

ALT, AST,GGT, TBIL, TC, TG, LDL-c, HOMA-IR, NAS score, |

Mohamad Nor 2021 [23] |

Malaysia |

17/22 |

180 d |

Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium |

Placebo |

ALT, AST, GGT, TC, TG,Steatosis score,Fibrosis score |

Barcelos 2023 [24] |

Brazil |

23/23 |

24 w |

probiotic mix |

Placebo |

FBG, Insulin, HOMA-IR, ALT, AST, GGT, TC, TG, BMI |

Escouto 2023 [10] |

Brazil |

23/25 |

180 d |

Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium lactis |

Placebo |

APRI score, NAFLD fibrosis score,ALT, AST, TNF-a, CRP, FBG, TC, TG,HOMA-IR, Insulin |

Laue 2023 [11] |

Germany |

59/59 |

12 w |

L. fermentum strains K7-Lb1, K8-Lb1 and K11-Lb3 |

Placebo |

ALT, AST, GGT, CRP, FBG, TC, TG, HOMA-IR, liver steatosis grade |

Aybo 2023 [27] |

Malaysia |

18/22 |

180 d |

6 bacterial species |

Placebo |

ALT, AST, GGT, FBG, TC, TG, |

Abd 2024 [16] |

Egypt |

25/25 |

12 w |

Lactèol Fort |

Nonplacebo |

ALT, AST, fibrosis score |

Lin 2024 [12] |

Taiwan |

15/11 |

60 d |

TSF331, TSR332, and TSP05 |

Placebo |

AST, ALT, UA, gut microbiota |

Table 1. Characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis

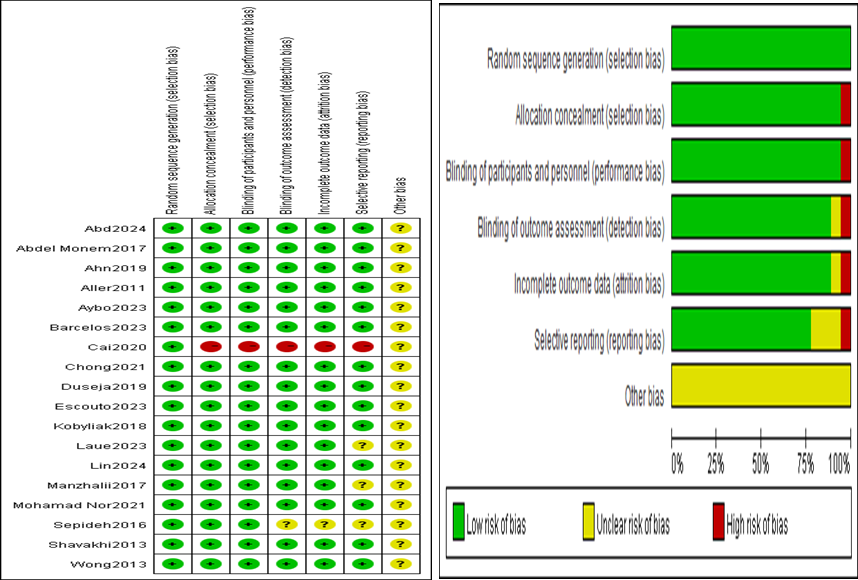

Risk of bias within studies

The risk of bias within the 18 studies included in this meta-analysis is summarized in Figure 2, showing the risk of bias graph and the risk of bias summary.

Figure 2. Risk of bias graph and risk of bias summary

Synthesis of results

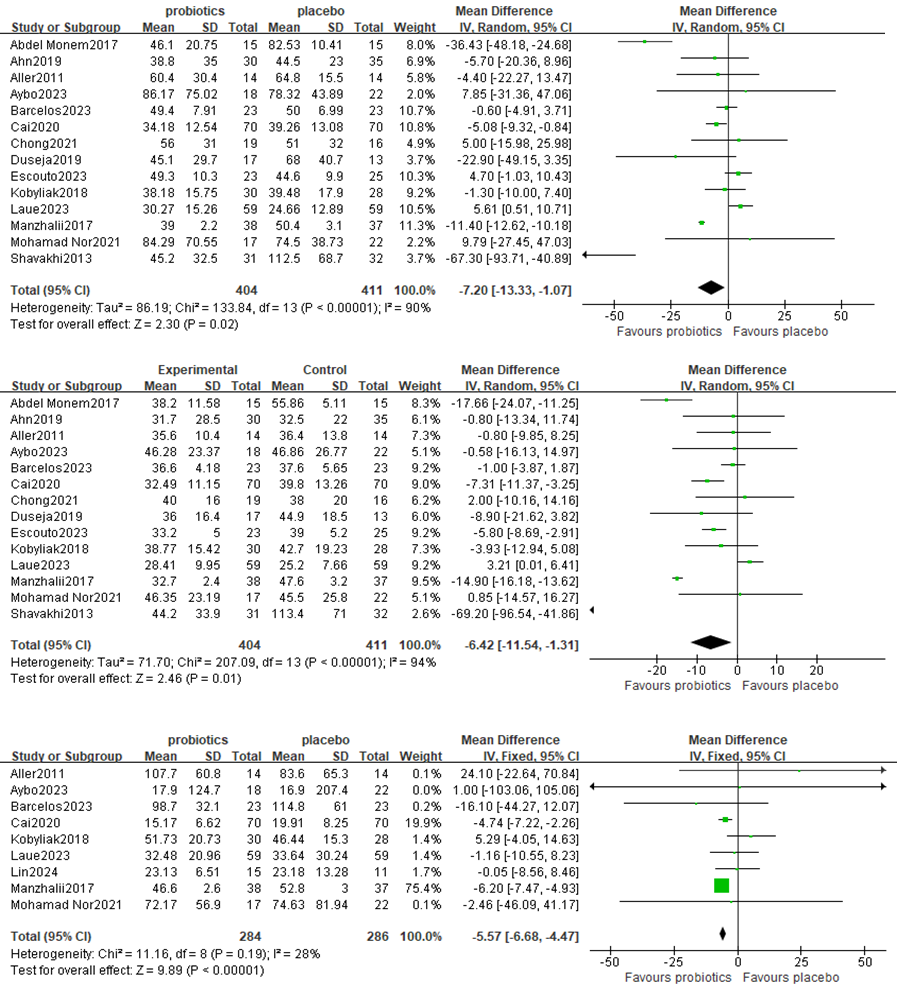

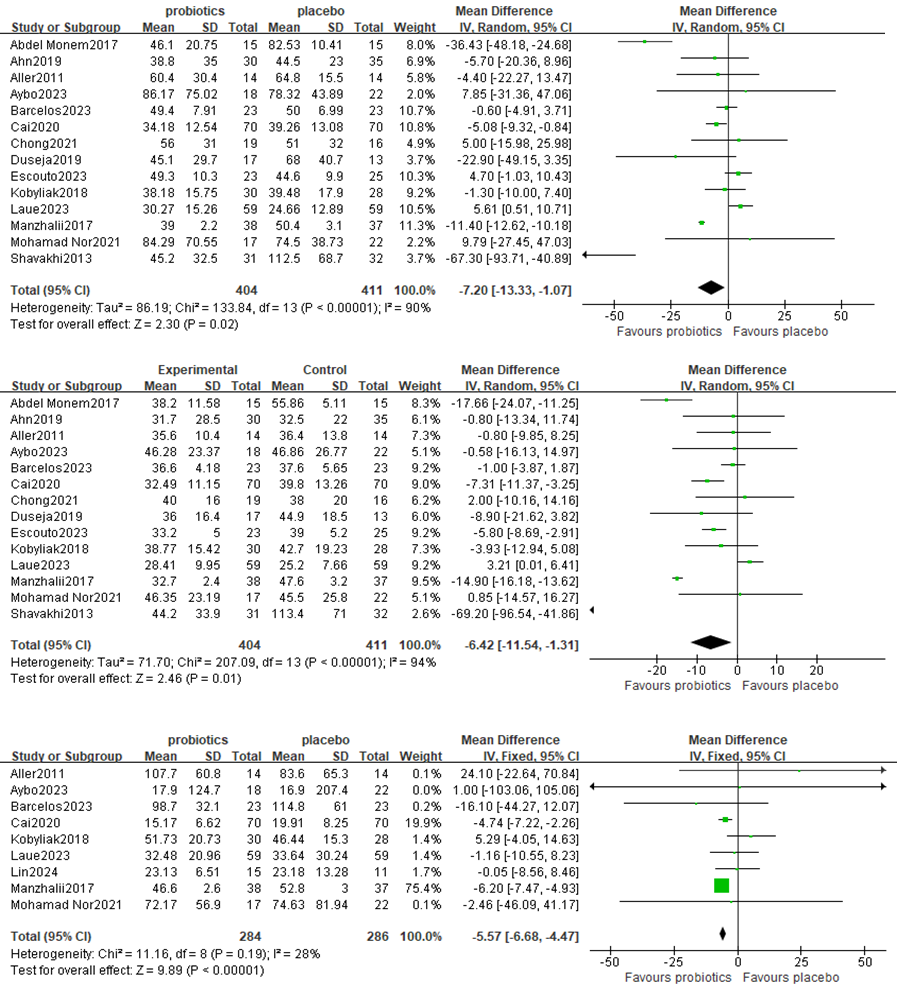

1. Effect on liver function

A meta-analysis of liver function was performed among studies that reported ALT, AST and GGT levels. A total of 14 RCTs involving 815 patients reported the pooled effect of probiotic supplementation on ALT levels. These trials showed heterogeneity in the consistency of the trial results (chi square=133.84, p<0.00001; I2=90%); therefore, a random effects model was used for the statistical analysis. Overall, the results of the meta-analysis suggested that probiotic regulation could reduce ALT in patients with MAFLD, as shown in Figure 3A [MD: −9.09 (−10.15, −8.03), p<0.00001]. Sensitivity analysis revealed that removing an individual trial did not change the overall effect.

Figure 3. Forest plot comparing ALT, AST and GGT levels

Fourteen studies, including a total of 815 participants, were used to examine the pooled effect of probiotic supplementation on AST levels. The trials showed heterogeneity in the consistency of the trial results (chi square=304.73, p<0.00001; I2=96%); therefore, a random effects model was used for the statistical analysis. A meta-analysis revealed a significant beneficial effect of probiotics compared with the control group in decreasing the level of AST [MD: −8.52 (−9.48, −7.56), p<0.0001] (Figure 3B).

Nine studies, including 570 participants, presented the pooled effect of probiotic supplementation on GGT levels. The trials showed heterogeneity in the consistency of the trial results (chi square=11.16, p<0.00001; I2=28%); therefore, a random effects model was used for the statistical analysis. A meta-analysis revealed a significant beneficial effect of probiotics compared with the control group in decreasing the level of GGT [MD: −5.57 (−6.68, −4.47), p<0.0001] (Figure 3C).

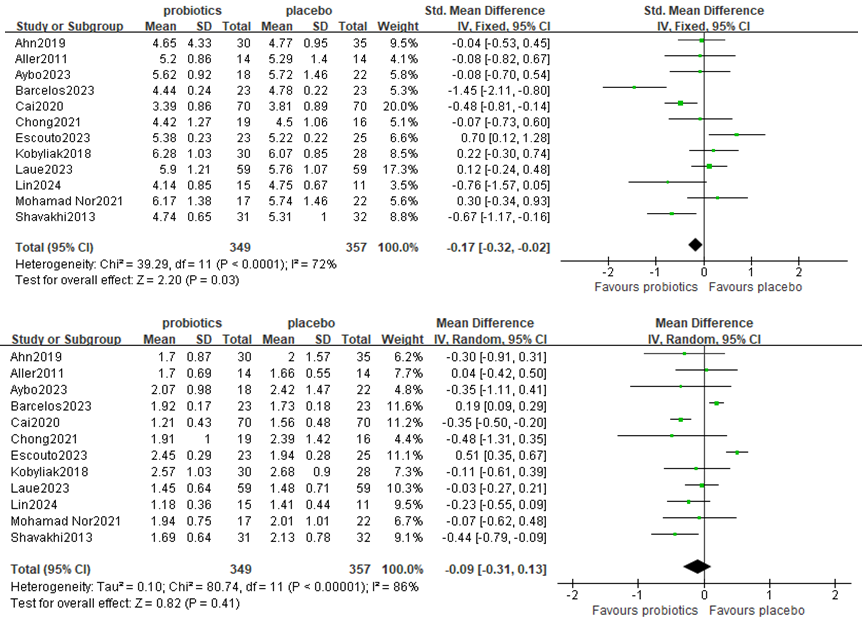

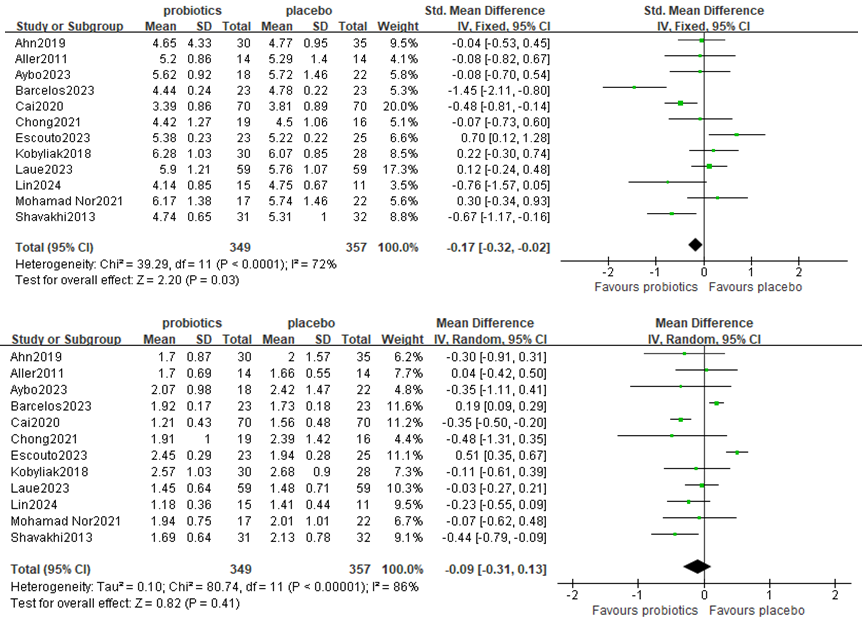

2. Effects on lipid metabolism

Twelve studies, including 706 participants, used TC levels to measure outcomes. The trials showed heterogeneity in the consistency of the trial results (chi-square = 39.29, P <0.0001; I2 = 72%). A meta-analysis revealed a beneficial effect of probiotics compared with the control group in decreasing the TC level [MD:−0.17 (−0.32,−0.02), p=0.03] (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. Forest plot comparing TC and TG levels in lipid metabolism

Twelve studies, including 706 participants, used TG levels to measure outcomes. The trials showed heterogeneity in the consistency of the trial results (chi-square = 32.59, P < 0.0001; I2 = 72%). A forest plot showing the results of the meta-analysis on TG is displayed in Figure 4B, revealing no significant differences between the experimental and control groups [MD:−0.09 (−0.31,0.13), p=0.41].

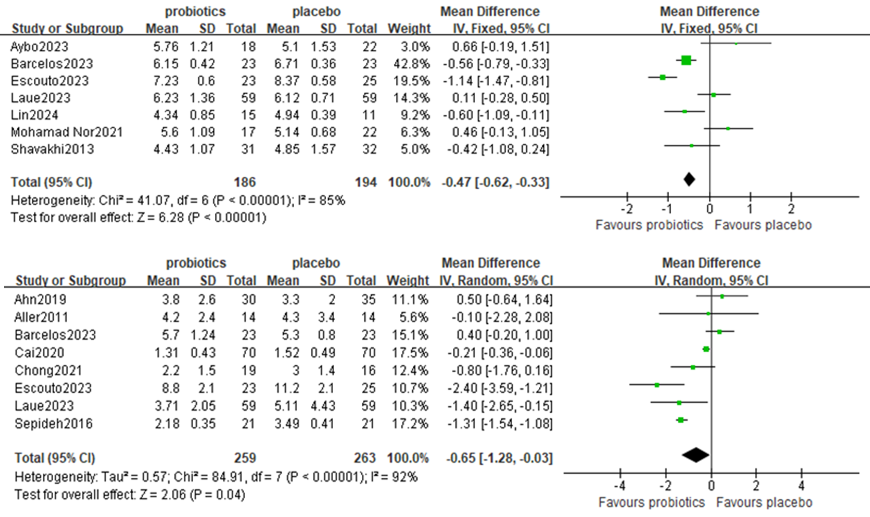

3. Effects on glucose and HOMA-IR

Seven studies, including 380 participants, used FBG levels to measure outcomes. The trials showed heterogeneity in the consistency of the trial results (chi-square = 41.07, P <0.00001; I2 = 85%). A meta-analysis revealed a significant beneficial effect of probiotics compared with the control group in decreasing the level of FBG [MD: −0.47 (−0.62, −0.33), p<0.00001] (Figure 5A).

Figure 5. Forest plot comparing FBG and HOMA-IR levels

Eight studies, including 522 participants, used the HOMA-IA levels to measure outcomes. The trials showed heterogeneity in the consistency of the trial results (chi-square = 84.91, P <0.00001; I2 = 92%); therefore, a random effects model was used for the statistical analysis. A meta-analysis revealed a beneficial effect of probiotics compared with the control group in decreasing the level of HOMA-IR [MD: −0.65 (−1.28, −0.03), p=0.04] (Figure 5B).

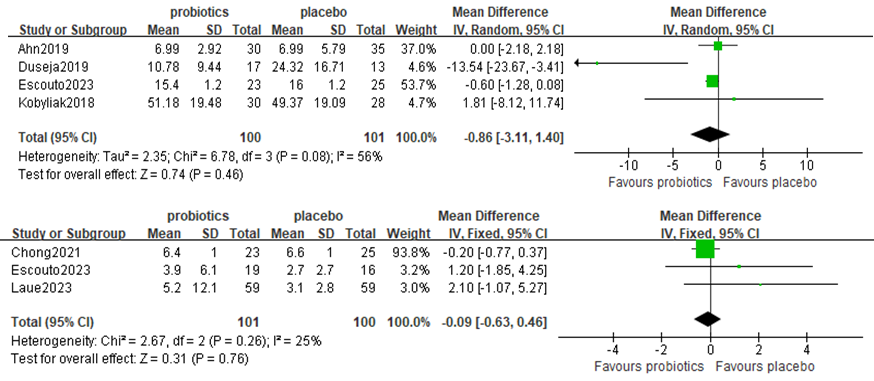

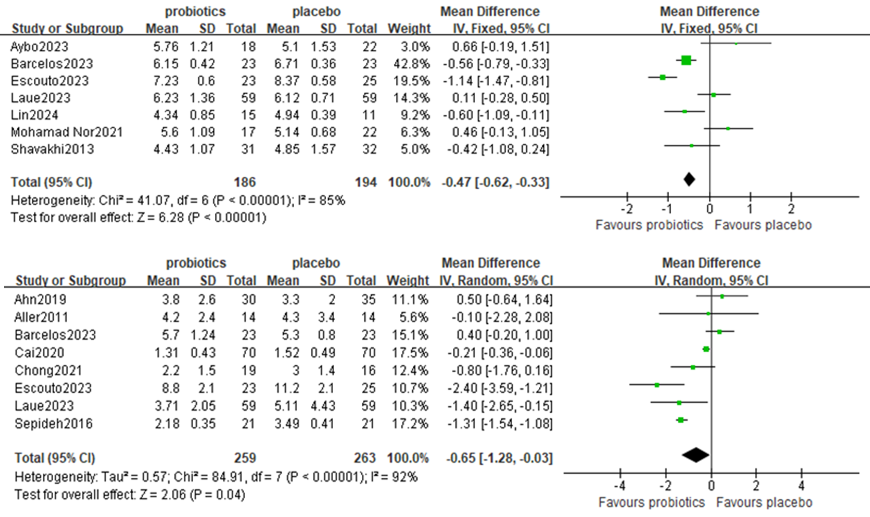

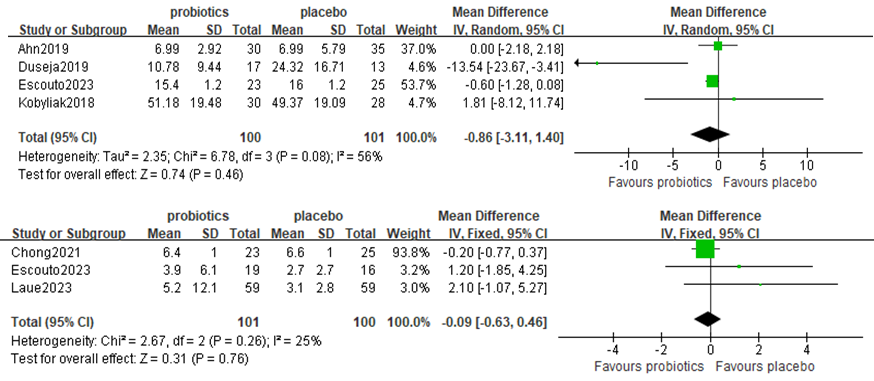

4. Effect on inflammation biomarkers

Four studies, including 201 participants, used TNF-α levels to measure outcomes. The trials showed heterogeneity in the consistency of the trial results (chi-square = 32.59, P=0.08; I2 = 56%). A forest plot showing the results of the meta-analysis of TNF-a is displayed in Figure 6A, revealing no significant differences between the experimental and control groups [MD: −0.59 (−1.24,0.06), p=0.07] (Figure 6A).

Figure 6. Forest plot comparing TNF-a and CRP levels

Three studies, including 201 participants, used CRP levels to measure outcomes. The trials showed heterogeneity in the consistency of the trial results (chi-square = 2.67, P=0.26; I2 = 25%). A forest plot showing the results of the meta-analysis of CRP is displayed in Figure 6B, revealing no significant differences between the experimental and control groups [MD: 0.28 (−0.94, 1.50), p=0.65] (Figure 6B).

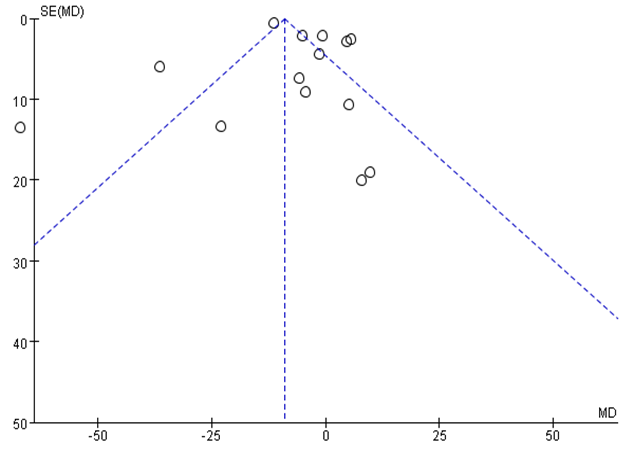

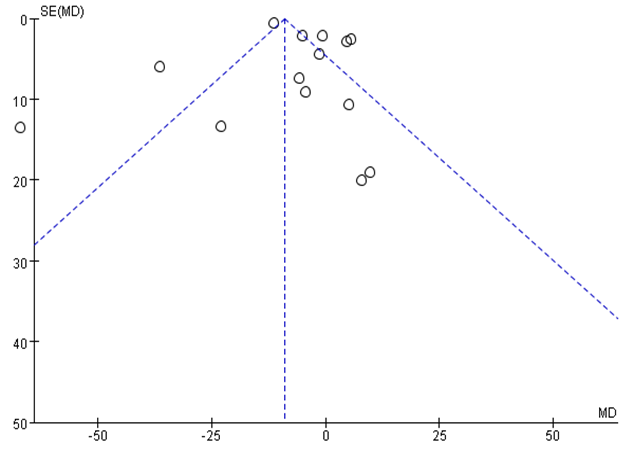

Publication bias

Funnel plot analysis of the 14 RCTs of ALT levels revealed an asymmetric distribution indicating the presence of publication bias (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Funnel plot analysis comparing ALT levels

Discussion

Summary of evidence

This study performed a systematic review and quantitative analysis of the scientific literature to assess the therapeutic effectiveness of probiotic interventions in MAFLD. The meta-analysis incorporated data from 18 RCTs, involving 962 participants, with a focus on adult populations. This study evaluated the impact of probiotic supplementation on hepatic enzyme profiles, glycemic and lipid metabolic parameters, and systemic inflammatory markers in MAFLD patients. The synthesized evidence demonstrated that probiotic administration significantly reduced total cholesterol levels; improved hepatic enzyme levels; and increased the levels of glucose metabolism indicators, such as ALT, AST, GGT, FBG and HOMA-IR, compared with those in placebo controls. Nevertheless, there appears to be little effect of probiotic supplementation on TG and inflammatory biomarkers (CRP and TNF-a).

Abnormalities in the gut–liver axis, including intestinal microecology imbalance, intestinal bacterial overgrowth, increased intestinal permeability, or intestinal leakage, play a role in the occurrence and development of MAFLD [29]. Probi-otic supplementation for patients with MAFLD is aimed at restoring the normal gut microbiota, thereby reducing liver inflammation. This may be the rationale for treating MAFLD with probiotics. Increases in the serum levels of hepatic enzymes, such as AST, ALT, ALP, and GGT, are indicative of liver damage.

The progression of MAFLD, which leads to elevated hepatic enzymes, aligns with the ‘two-hit theory’, where fat accumulation serves as the initial factor (‘first hit’), and subsequent liver injury from necroinflammation and oxidative stress constitutes the ‘second hit’ [30]. The “multiple-hit” pathological hypothesis has been widely recognized in recent years [31,32]. Studies demonstrate the efficacy of microbial therapy in reducing hepatic enzymes in individuals with NAFLD. Treatment with probiotics specifically lowered levels of ALT, AST and GGT, with GGT recognized as a highly sensitive marker for liver damage and a novel indicator of inflammation and oxidative stress [33].

In this review, we found that probiotics were closely associated with a decrease in AST, ALT, and GGT levels, suggesting that probiotic supplementation in NAFLD patients may have protective effects on liver function by regulating the composition and metabolism of the gut microbiota. This conclusion is consistent with previous meta-analyses by Loman [34] and Wang [35].

A key factor in the pathogenesis of MAFLD is insulin resistance [36], which contributes to the progression of hepatic steatosis to more severe forms of liver disease, including NASH and cirrhosis. The intricate link between NAFLD and DM is well documented, with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinism serving as hallmark features of NAFLD. Studies have reported elevated fasting insulin levels in NAFLD patients, even in nondiabetic individuals [37].

HOMA-IR, a key indicator of insulin resistance, is particularly useful in evaluating NAFLD among diabetic patients [38,39] and has been identified as an independent predictor for advanced liver fibrosis in NAFLD patients [40]. Further-more, the FBG levels, another indicator of glycemic control, are significantly greater in individuals with NAFLD [41,42]. This study demonstrated that therapy with probiotics can significantly reduce insulin and FBG levels, highlighting the potential of these interventions in improving insulin resistance in the NAFLD population.

The pathophysiology of MAFLD involves complex interactions between lipid metabolism and various metabolic disturbances, including insulin resistance and dyslipidemia. Dyslipidemia, characterized by elevated serum TG and LDL-C levels, along with reduced HDL levels, is closely linked to MAFLD and its comorbidities [43,44]. The gut microbiota plays a vital role in lipid metabolism,a process influenced by microbiota-derived metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids and lipopolysaccharides [45,46]. Probiotics affect lipid profiles through various mechanisms, including modulation of the gut microbiota composition, enhancement of intestinal barrier function, and regulation of systemic inflammation. Clinical studies have demonstrated that probiotic supplementation can lead to significant reductions in total cholesterol, triglycerides, and LDL-C while increasing HDL-C levels in hyperlipidemic patients [47]. In this review, we found that probiotics were closely associated with a decrease in TC, suggesting that probiotic supplementation in MAFLD patients may have protective effects on cholesterol metabolism. However, we noticed that the TG levels were not significantly different between MAFLD patients and controls.

The inflammatory response in MAFLD is driven primarily by oxidative stress and dysregulated lipid metabolism, which can activate proinflammatory pathways. Elevated levels of inflammatory markers, such as CRP and TNF-α, have been linked with NAFLD [48]. Previous studies have explored the beneficial effects of probiotics on inflammatory markers [49,50]. A previous systematic review and meta-analysis highlighted the beneficial effects of probiotics on liver function and inflammation in individuals with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease [51]; however, in our study, probiotic treatment had no significant effect on CRP or TNF-a. The effects of probiotics on these markers have yet to be elucidated.

Limitations

Because meta-analysis involves secondary research, the evidence is influenced by the quality of the included studies. There are several limitations in our meta-analysis that should be mentioned. First, the quality of some studies included was low. More high-quality, multicenter, high-standard RCTs are needed in the future. Second, we searched for unpublished articles in English but were unable to identify all relevant unpublished data for inclusion. Publication bias was also evident through a funnel plot analysis. Third, since we searched for articles published only in English, reporting bias may exist.

Conclusion

Our meta-analysis revealed that probiotic consumption among adult patients with MAFLD has a beneficial effect on metabolic indicators by significantly reducing the levels of ALT, AST, GGT, TC, FBG and HOMA-IR. However, this intervention had no statistically significant effect on TC, CRP or TNF-a levels. There is promising evidence that probiotic supplementation can reduce liver enzyme levels and regulate glycometabolism and cholesterol metabolism in patients with MAFLD. Since some of the RCTs included in our meta-analysis were poorly reported and of low quality, the results should be interpreted with caution. More multicenter, high-quality RCTs are needed to evaluate the therapeutic effects of probiotics in adult patients with MAFLD.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this manuscript.

References

- Davis TME (2021) Diabetes and metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. Metabolism 123: 154868. [Crossref]

- Wang X, Xie Q (2021) Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) and viral hepatitis. J Clin Transl Hepatol 10: 128. [Crossref]

- Yang K, Song M (2023) New insights into the pathogenesis of metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD): Gut-liver-heart crosstalk. Nutrients 15: 3970. [Crossref]

- Wang YY, Lin HL, Wang KL, Que GX, Cao T, et al. (2023) Influence of gut microbiota and its metabolites on progression of metabolic associated fatty liver disease. Chin Med Sci J 38: 286-296. [Crossref]

- Dongoran RA, Tu FC, Liu CH (2023) Current insights into the interplay between gut microbiota-derived metabolites and metabolic-associated fatty liver disease. Tzu Chi Med J 35: 290-299. [Crossref]

- Bjarnason I, Sission G, Hayee B (2019) A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of a multi-strain probiotic in patients with asymptomatic ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Inflammopharmacology 27: 465-473. [Crossref]

- Martoni CJ, Srivastava S, Damholt A, Leyer GJ (2023) Efficacy and dose response of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 29: 4451-4465. [Crossref]

- Lai H, Li Y, He Y, Chen F, Mi B, et al. (2023) Effects of dietary fibers or probiotics on functional constipation symptoms and roles of gut microbiota: A double-blinded randomized placebo trial. Gut Microbes 15: 2197837. [Crossref]

- Shi J, Li F (2023) Clinical study of probiotics combined with lactulose for minimal hepatic encephalopathy treatment. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 35: 777-781. [Crossref]

- Escouto GS, Port GZ, Tovo CV, Fernandes SA, Peres A, et al. (2023) Probiotic supplementation, hepatic fibrosis, and the microbiota profile in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: A randomized controlled trial. J Nutr 153: 1984-1993. [Crossref]

- Laue C, Papazova E, Pannenbeckers A, Schrezenmeir J (2023) Effect of a probiotic and a synbiotic on body fat mass, body weight and traits of metabolic syndrome in individuals with abdominal overweight: A human, double-blind, randomised, controlled clinical study. Nutrients 15: 3039. [Crossref]

- Lin JH, Lin CH, Kuo YW, Liao CA, Chen JF, et al. (2024) Probiotic Lactobacillus fermentum TSF331, Lactobacillus reuteri TSR332, and Lactobacillus plantarum TSP05 improved liver function and uric acid management-A pilot study. PLoS One 19: e0307181. [Crossref]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, et al. (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372: n71. [Crossref]

- Aller R, De Luis DA, Izaola O, Conde R, Gonzalez Sagrado M, et al. (2011) Effect of a probiotic on liver aminotransferases in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients: A double blind randomized clinical trial. Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 15: 1090-1095. [Crossref]

- Wong VW, Won GL, Chim AM, Chu WC, Yeung DK, et al. (2013) Treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis with probiotics. A proof-of-concept study. Ann Hepatol 12: 256-262. [Crossref]

- Abd El Hamid AA, Mohamed AE, Mohamed MS, Amin GE, Elessawy HA, et al. (2024) The effect of probiotic supplementation on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) fibrosis score in patients attending a tertiary hospital clinic in Cairo, Egypt. BMC Gastroenterol 24: 354. [Crossref]

- Abdel Monem SM (2017) Probiotic Therapy in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in Zagazig university hospitals. Euroasian J Hepatogastroenterol 7: 101-106. [Crossref]

- Manzhalii E, Virchenko O, Falalyeyeva T, Beregova T, Stremmel W, et al. (2017) Treatment efficacy of a probiotic preparation for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: A pilot trial. J Dig Dis 18: 698-703. [Crossref]

- Kobyliak N, Abenavoli L, Mykhalchyshyn G, Kononenko L, Boccuto L, et al. (2018) A multi-strain probiotic reduces the fatty liver index, cytokines and aminotransferase levels in NAFLD patients: Evidence from a randomized clinical trial. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 27: 41-49. [Crossref]

- Ahn SB, Jun DW, Kang BK, Lim JH, Lim S, et al. (2019) Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of a multispecies probiotic mixture in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Sci Rep 9: 5688. [Crossref]

- Duseja A, Acharya SK, Mehta M, Chhabra S, Rana S, et al. (2019) High potency multistrain probiotic improves liver histology in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): A randomised, double-blind, proof of concept study. BMJ Open Gastroenterol 6: e000315. [Crossref]

- Chong PL, Laight D, Aspinall RJ, Higginson A, Cummings MH, et al. (2021) A randomised placebo controlled trial of VSL#3(®) probiotic on biomarkers of cardiovascular risk and liver injury in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMC Gastroenterol 21: 144. [Crossref]

- Mohamad Nor MH, Ayob N, Mokhtar NM, Raja Ali RA, Tan GC, et al. (2021) The effect of probiotics (MCP(®) BCMC(®) Strains) on hepatic steatosis, small intestinal mucosal immune function, and intestinal barrier in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Nutrients 13: 3192. [Crossref]

- Barcelos STA, Silva-Sperb AS, Moraes HA, Longo L, de Moura BC, et al. (2023) Oral 24-week probiotics supplementation did not decrease cardiovascular risk markers in patients with biopsy proven NASH: A double-blind placebo-controlled randomized study. Ann Hepatol 28: 100769. [Crossref]

- Sepideh A, Karim P, Hossein A, Leila R, Hamdollah M, et al. (2016) Effects of multistrain probiotic supplementation on glycemic and inflammatory indices in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A double-blind randomized clinical trial. J Am Coll Nutr 35: 500-505. [Crossref]

- Cai GS, Su H, Zhang J (2020) Protective effect of probiotics in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Medicine 99: e21464. [Crossref]

- Ayob N, Muhammad Nawawi KN, Mohamad Nor MH, Raja Ali RA, Ahmad HF, et al. (2023) The effects of probiotics on small intestinal microbiota composition, inflammatory cytokines and intestinal permeability in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Biomedicines 11: 640. [Crossref]

- Shavakhi A, Minakari M, Firouzian H, Assali R, Hekmatdoost A, et al. (2013) Effect of a probiotic and metformin on liver aminotransferases in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: A double blind randomized clinical trial. Int J Prev Med 4: 531-537. [Crossref]

- Guerra JVS, Dias MMG, Brilhante A, Terra MF, Garcia-Arevalo M, et al. (2021) Multifactorial basis and therapeutic strategies in metabolism-related diseases. Nutrients 13: 2830. [Crossref]

- Shatta MA, El-Derany MO, Gibriel AA, El-Mesallamy HO (2023) Rhamnetin ameliorates non-alcoholic steatosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in vitro. Mol Cell Biochem 478: 1689-1704. [Crossref]

- Karkucinska-Wieckowska A, Simoes ICM, Kalinowski P, Lebiedzinska‐Arciszewska M, Zieniewicz K, et al. (2022) Mitochondria, oxidative stress and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A complex relationship. Eur J Clin Invest 52: e13622. [Crossref]

- García-Berumen CI, Vargas-Vargas MA, Ortiz-Avila O, Piña–Zentella RM, Ramos-Gómez M, et al. (2022) Avocado oil alleviates non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by improving mitochondrial function, oxidative stress and inflammation in rats fed a high fat-High fructose diet. Front Pharmacol 13: 1089130. [Crossref]

- Wang P, Zhang J, Liu HW, Hu XX, Feng LL, et al. (2017) An efficient two-photon fluorescent probe for measuring γ-glutamyltranspeptidase activity during the oxidative stress process in tumor cells and tissues. Analyst 142: 1813-1820. [Crossref]

- Loman BR, Hernández-Saavedra D, An R, Rector RS (2018) Prebiotic and probiotic treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Rev 76: 822-839. [Crossref]

- Wang Q, Wang Z, Pang B, Zheng H, Cao Z, et al. (2022) Probiotics for the improvement of metabolic profiles in patients with metabolic-associated fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 13: 1014670. [Crossref]

- Pal SC, Eslam M, Mendez-Sanchez N (2022) Detangling the interrelations between MAFLD, insulin resistance, and key hormones. Hormones (Athens) 21: 573-589. [Crossref]

- Grzych G, Chávez-Talavera O, Descat A, Thuillier D, Verrijken A, et al. (2021) NASH-related increases in plasma bile acid levels depend on insulin resistance. JHEP Rep 3: 100222. [Crossref]

- Pérez-Mayorga M, Lopez-Lopez JP, Chacon-Manosalva MA, Castillo MG, Otero J, et al. (2022) Insulin resistance markers to detect nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a male hispanic population. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022: 1782221. [Crossref]

- Han JE, Shin HB, Ahn YH, Cho HJ, Cheong JY, et al. (2022) Relationship between the dynamics of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and incident diabetes mellitus. Sci Rep 12: 2538. [Crossref]

- Ballestri S, Nascimbeni F, Romagnoli D, Lonardo A (2016) The independent predictors of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and its individual histological features: Insulin resistance, serum uric acid, metabolic syndrome, alanine aminotransferase and serum total cholesterol are a clue to pathogenesis and candidate targets for treatment. Hepatol Res 46: 1074-1087. [Crossref]

- Nowrouzi-Sohrabi P, Rezaei S, Jalali M, Ashourpour M, Ahmadipour A, et al. (2021) The effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists on glycemic control and anthropometric profiles among diabetic patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Pharmacol 893: 173823. [Crossref]

- Ebrahimzadeh A, Mohseni S, Safargar M, Mohtashamian A, Niknam S, et al. (2024) Curcumin effects on glycaemic indices, lipid profile, blood pressure, inflammatory markers and anthropometric measurements of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Complement Ther Med 80: 103025. [Crossref]

- González-Domínguez Á, Visiedo-García FM, Domínguez-Riscart J, González-Domínguez R, Mateos RM, et al. (2020) Iron metabolism in obesity and metabolic syndrome. Int J Mol Sci 21: 5529. [Crossref]

- Kasper P, Martin A, Lang S, Kuetting F, Goeser T, et al. (2021) NAFLD and cardiovascular diseases: A clinical review. Clin Res Cardiol 110: 921-937. [Crossref]

- Wang N, Dilixiati Y, Xiao L, Yang H, Zhang Z (2024) Different short-chain fatty acids unequally modulate intestinal homeostasis and reverse obesity-related symptoms in lead-exposed high-fat diet mice. J Agric Food Chem 72: 18971-18985. [Crossref]

- Schoeler M, Caesar R (2019) Dietary lipids, gut microbiota and lipid metabolism. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 20: 461-472. [Crossref]

- Duan Y, Wang L, Ma Y, Ning L, Zhang X (2024) A meta-analysis of the therapeutic effect of probiotic intervention in obese or overweight adolescents. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 15: 1335810. [Crossref]

- Thomsen KL, Robertson FP, Holland-Fischer P, Davidson BR, Mookerjee RP, et al. (2019) The macrophage activation marker soluble cd163 is associated with early allograft dysfunction after liver transplantation. J Clin Exp Hepatol 9: 302-311. [Crossref]

- Yu JS, Youn GS, Choi J, Kim CH, Kim BY, et al. (2021) Lactobacillus lactis and Pediococcus pentosaceus-driven reprogramming of gut microbiome and metabolome ameliorates the progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Transl Med 11: e634. [Crossref]

- Javadi L, Khoshbaten M, Safaiyan A, Ghavami M, Abbasi MM, et al. (2018) Pro- and prebiotic effects on oxidative stress and inflammatory markers in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 27: 1031-1039. [Crossref]

- Pan Y, Yang Y, Wu J, Zhou H, Yang C, et al. (2024) Efficacy of probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics on liver enzymes, lipid profiles, and inflammation in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Gastroenterol 24: 283. [Crossref]