Abstract

This case report explores the Druid® impairment assessment app’s ability to monitor cognitive and motor impairment in a 21-year-old female patient who suffered and then recovered from a diagnosed head concussion. Her pre-established baseline score for the 1-minute Druid Rapid test was 33.8. Three days post-injury, she began to complete multiple daily tests. That day, her lowest daily Druid score was 57.4 (baseline + 23.6 points), indicating severe impairment. After later peaking at 62.5 (baseline + 28.7 points), her scores then improved steadily until her lowest daily score was 36.9 (baseline + 3.1 points). Later, even though she had received medical clearance to resume her normal activities, her Druid scores increased after her workplace training program presented greater physical demands, screen time, and stress. She discontinued testing once her lowest daily scores were close to or below her baseline for six days in a row; this occurred three months post-injury when her scores ranged from 30.1 (baseline – 3.7 points) to 36.3 (baseline + 2.5 points). These findings demonstrate Druid Rapid’s potential to serve as a simple, fast, inexpensive, and user-friendly tool that professionally diagnosed concussion patients can use each day at home or elsewhere to monitor their recovery progress. A series of elevated Druid impairment scores may signal that patients should adjust their activity level, screen time, and sleep schedule, or take other remedial or rehabilitative steps to expedite their full recovery, or in some cases, consult with their healthcare provider. Future research will examine Druid’s utility for daily monitoring of concussion recovery among athletes, first responders, and other populations.

Keywords

Concussion monitoring, Druid app, impairment assessment, recovery

Introduction

Concussion results in neurological impairment that manifests as diminished reaction time, balance, and coordination [1,2]. As Rier, et al. [3] noted, while “the damage may be too subtle for structural imaging to see, the functional consequences are detectable and persist after injury.” Standard clinical methods of assessment are required to diagnose concussion and determine when a patient has recovered fully [4]. However, there is also a need for a valid tool that can track the progress of concussion recovery. This tool should be accurate and reliable, of course, but also fast and inexpensive; it should be user-friendly so that patients can use it daily at home or elsewhere. With this information, patients can adjust their activity level, screen time, and sleep schedule to facilitate their recovery, and both patients and their healthcare providers can monitor their progress over time.

This case report explores the ability of the Druid® Rapid impairment assessment app to monitor cognitive and motor impairment in a 21-year-old female patient who suffered and then recovered from a concussion caused by a syncopal episode and subsequent fall with head injury. To document her informed consent, she signed a release that allows us to share her medical information under conditions of anonymity.

The Druid app

Druid assesses cognitive and motor impairment levels due to any cause or combination of causes, including cannabis and other drugs, alcohol, prescribed medications, fatigue, acute illness, injury, chronic medical conditions, severe emotional distress, and environmental conditions such as extreme heat or high altitude (Impairment Science, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA). Druid can determine if and to how much a person is impaired but not the reason for their impairment. Accordingly, like a thermometer, the app can be used as a screening or monitoring tool in a variety of settings.

There are two versions of the app: The original Druid Benchmark test (3 minutes) and the Druid Rapid test (1 minute) which has been calibrated to generate the same scores as the longer Benchmark test. Both versions operate on iOS devices (iPhone, iPad) and Android smartphones and tablets.

Grounded in neuroscience-based assessment methods, Druid Rapid requires users to perform two videogame-like, divided-attention tasks that assess reaction time, decision-making accuracy, hand-eye coordination, and time estimation, followed by a balance test. Table 1 presents a brief description of these tasks. The app continuously collects and integrates hundreds of measurements to calculate an impairment score that can range from 0 to 100 but in practice ranges from 25 to 75. When experienced Druid users are unimpaired and complete the test without becoming distracted, successive Druid tests typically vary by a mean absolute value of only 0.89 points (SD=0.71).

Task 1a |

A series of small squares and circles flash on the screen for half a second. One shape is designated as the target shape and the other as the control shape. As quickly as possible, the user touches the screen where a target shape appears, and touches a small oval at the top of the screen when a control shape appears. Halfway through the task, the target and control shapes are switched. |

Task 2a |

After the user presses the “Start” button, a series of circles flash on the screen for half a second. As quickly as possible, the user touches the screen wherever a circle appears. They hit the “Stop” button when they think 15 seconds have passed. |

Task 3 |

The user stands on their right leg for 15 seconds while holding a tablet or smartphone as still as possible in their left hand, after which they stand on their left leg for 15 seconds while holding the device in their right hand. |

Note: The stimulus sequence for Tasks 1 and 2 differ within specified parameters each time a person uses the app. |

Table 1. Druid Rapid’s tasks

1/17 |

Began a multi-week training program for her new job at a dialysis center, which initially involved minimal screen time and limited physical activity |

1/20 |

Diagnosed at the ER with a concussion after a syncopal episode and fall at home |

1/22 |

Asked by Impairment Science, Inc., to do three daily Druid Rapid tests in a row until she recovered |

1/25 |

Returned to work full-time and resumed the training program |

2/15 |

Unilaterally discontinued Druid testing after getting a score of 36.9, just 3.1 points above her 10/24/22 baseline of 33.8a |

2/17 |

As her training continued through 4/3, FGH gradually took on expanded duties with increasing physical demands, screen time, and stress; near the end of this period, she was managing several patients at a time |

3/02 |

Self-initiated Druid testing one day before her follow-up appointment |

3/03 |

Received medical clearance to resume all of her normal activities, including smartphone use |

3/07 |

Unilaterally decided to discontinue Druid testing despite elevated scores |

3/09 |

Alerted to resume Druid testing due to her recent scores being well above her baseline score |

3/10 |

Resumed daily Druid testing, which was sustained through 4/28 |

4/04 |

Began an intensive online training program and at-home study to prepare for a certification exam on 4/14 |

4/11 |

Reported experiencing frequent headaches and dizziness during the past week |

4/14 |

Passed the certification exam, after which she had two days off from work |

4/17 |

Assumed full duties at the dialysis center, managing 8 to 10 patients at a time |

4/28 |

Instructed to discontinue Druid testing after her lowest daily scores were close to or below her baseline for six days in a rowb |

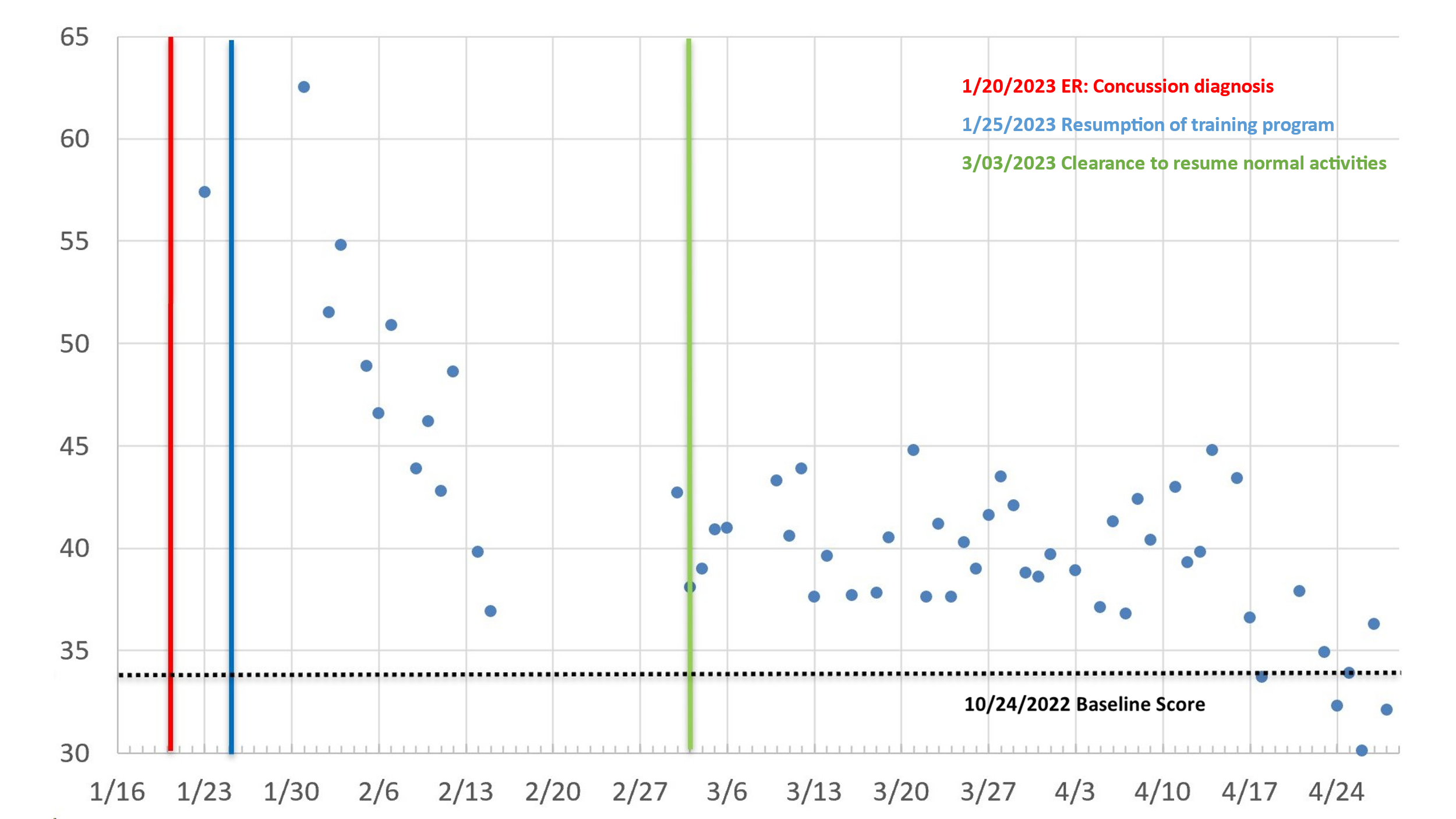

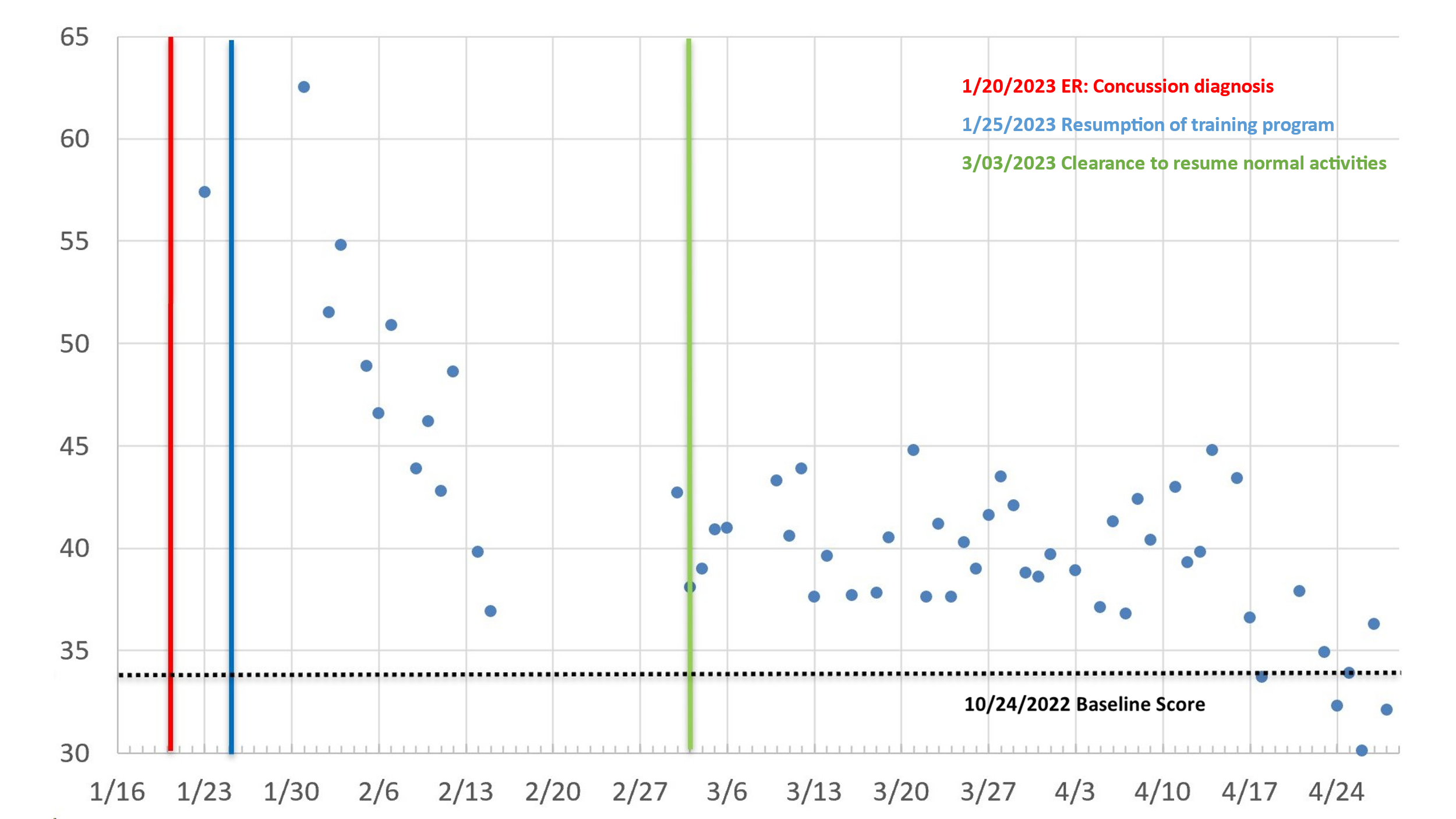

Note: a On days when FGH took 2 to 4 tests, her lowest Druid score was compared to her baseline score (see Figure 1). b From 4/23 to 4/28, FGH’s lowest daily scores ranged from 30.1 (baseline –3.7 points) to 36.3 (baseline + 2.5 points) |

Figure 1. Lowest (Best) Daily Druid Impairment Scores for Patient FGH Following Her Concussion Diagnosis. Note: Except as indicated here, each day’s reported is the lowest (best) score of three daily Druid Rapid tests. Also displayed are the lowest of two tests on January 31, March 2, and March 21 and of four tests on March 16 and April 27. Scores are not displayed for dates with only one test: January 22, 29, and 30, March 20, and April 19 and 22. Additional dates without a displayed score are days with no tests: 1/24-1/29, 2/1, 2/4, 2/8, 2/13, 2/16-3/1, 3/7-3/9, 3/15, 3/17, 4/2, 4/4, 4/10, 4/15, and 4/20

Table 2. Key events for Patient FGH from January 17, 2023, to April 28, 2023

Within specified parameters, the stimulus patterns that Druid Rapid presents in Tasks 1 and 2 are different each time a person uses the app. For example, in Task 1, the app randomly decides the order, speed, and location of the target and control shapes so that users cannot predict what will be shown next. As a result, once a user establishes their baseline score, their performance will improve only slightly, if at all, when they repeatedly use the app under similar conditions. Of course, their performance could change under various circumstances, such as when users are showing cognitive-motor decline due to concussion, chronic medical conditions, acute illness, recent use of alcohol, cannabis, or another psychoactive drug, or fatigue due to sleep deprivation or physical or mental exertion.

Our standard procedure for research studies calls for participants to practice Druid until the participant becomes familiarized with the app. Next, they should complete at least three additional tests until they produce two out of three successive scores that fall within ≤ ± 3.0 points of each other. We have found that only a small percentage of research participants require more than five tests. The initial baseline score is the mean of the two qualifying tests, which will typically range between 35.0 and 50.0 but can be lower or higher for some individuals. Future test scores can be compared against the baseline score.

Druid validation studies

To date, three independently conducted research studies have demonstrated that Druid is an accurate, sensitive, and objective assessment tool. Richman, et al. [5] validated the Druid Benchmark’s ability to detect cognitive and motor impairment associated with an alcohol breathalyzer reading (BrAC) of 0.08%. At baseline, the study participants’ mean impairment score was 44.3; after reaching a BrAC of 0.08% or higher, there was a statistically significant increase to 57.1.

A research team at The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine tested Druid with infrequent cannabis users [6]. Study participants completed a series of double-blind testing sessions on six different days: a) ingested cannabis brownies containing 0, 10, or 25 mg of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), and b) inhaled vaporized cannabis containing 0, 5, or 20 mg of THC. The 10 mg oral dose and the 5 mg vaporized dose produced positive subjective effects, however, 10 assessment methods, one being Druid Benchmark, did not detect significantly greater impairment relative to the 0 mg placebo. In the 25 mg oral THC condition, the participants’ Druid performance indicated significant impairment relative to baseline at 2 to 5 hours after ingestion and both immediately and after 1 hour in the 20 mg vaped THC condition. The investigators concluded that Druid “was the most sensitive measure of impairment when compared to the other cognitive performance tasks administered…as well as several common field sobriety tests.”

Karoly and colleagues [7] reported two research studies with frequent cannabis users. Both studies found that after consuming high-potency cannabis, the study participants generated Druid Benchmark scores that indicated substantial impairment when compared to their baseline scores. As expected, their impairment scores increased, peaked, and then decreased over the next few hours. The importance of the studies is highlighted by the fact that participants varied in the type (i.e., flower or concentrate), method, and amount of cannabis consumed.

Collectively, these three research validation studies verified the Druid app’s value as a general test of cognitive and motor impairment. Thus, when a long-time Druid user with a known Druid Rapid baseline score informed us that she had fallen and suffered a concussion, we immediately asked her to take three Druid Rapid tests per day during the course of her recovery. Our plan called for comparing each day’s lowest test score against her baseline score, which she had established approximately three months before her injury as part of another internal Impairment Science study.

Patient’s medical history

The patient (to be called “FGH”) was a 21-year-old female who presented to the Emergency Room (ER) at a hospital in the Mountain West after she suffered a head injury following a syncopal episode and subsequent fall on January 20, 2023.

As a new employee at a dialysis center, FGH started a weeks-long training program on January 17, 2023, which initially consisted of reading hardcopy materials, observing staff, and practicing the protocol under supervision, all with minimal screen time and limited physical activity. She reported that on January 20, she returned home after a 4:00 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. shift and lay down on her couch to rest. Upon standing up several minutes later, she felt light-headed, fell, and hit her head on her living room’s concrete floor, after which she experienced nausea and vomited one time. Her boyfriend immediately called an ambulance.

The examining ER physician recorded that FGH had sustained a 1.5 cm non-opposing left parietal scalp laceration through the skin and soft tissues but not the galea aponeurosis. On physical examination, she was awake, alert, and fully oriented. Her vital signs were as follows: 1) temperature – 98.0 F.; 2) blood pressure – 131/71; 3) pulse – 87; 4) pulse oximetry – 99% saturation on room air; and 5) respiration – 22 breaths/minute, with rates above 20 indicating tachypnoea [8].

A thorough physical exam discovered no concerning anomalies. Her electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm with normal morphologies and intervals. Laboratory tests conducted that day – including blood chemistries, serum HCG, high-sensitivity troponin, blood counts, and blood differential – were likewise unremarkable. Subsequent bloodwork indicated a high Total Iron-Binding Capacity (TIBC) score.

A head CT scan without contrast showed soft tissue swelling and the left parietal scalp laceration, but otherwise, her cranium and brain appeared to be normal. Her neurological exam was also normal. Her Glasgow Coma Scale score was 15/15 indicating that she was fully awake and responsive [9].

Her medical history included two previous syncopal episodes when she was in her teens, one of which occurred after skipping a meal; no other underlying cause or diagnosis was established for either incident. Her medical history also included patent foramen ovale, Raynaud’s phenomenon, anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome, dysfunctional uterine bleeding, and idiopathic gastroparesis. Upon admission, her current medications included aspirin, budesonide, cisapride, norethindrone, and vitamin D3.

She received droperidol and ondansetron for nausea, acetaminophen for pain, and intravenous normal saline. Her scalp laceration was irrigated, explored, and closed with two 4-0 ProleneTM sutures. After approximately three hours of observation and treatment, she was diagnosed with a concussion and discharged with instructions to rest, take precautions when standing up or changing positions, limit her screen time, and return if she were to experience any worsening symptoms. On March 3, FGH returned to the hospital for a follow-up examination and received medical clearance to resume all of her normal activities, including smartphone use.

Materials and methods

On October 24, 2022, three months before her head injury, FGH had established a baseline score of 33.8 using the 1-minute Druid Rapid test on her iPhone 13.2.

She resumed her workplace training program on January 25, just five days after receiving her concussion diagnosis. Initially, this involved reading and reviewing extensive training materials, some online but mostly hardcopy documents; observing the staff operate the dialysis machines; and practicing the easier aspects of the protocol under supervision. When interviewed by email, she stated that this phase of the training involved limited physical activity and minimal screen time.

Beginning on January 23, FGH began at our request to complete three daily tests in a row for the duration of her recovery. When interviewed, she reported doing most of her tests in the evening throughout the study period, having napped on most days after 11-hour shifts at the dialysis center, and then giving herself a couple of hours to wake up fully. On most days, FGH completed three tests, but on 3 days she completed two (1/31, 2/22, and 2/21), and on 2 days she completed four (3/16 and 4/27). On six days she completed only one test (1/22, 1/29, 1/30, 3/20, 4/1, and 4/22). There were three time periods and 11 additional days when she did not complete any Druid tests (1/24-1/29, 2/1, 2/4, 2/8, 2/13, 2/16-3/1, 3/7-3/9, 3/15, 3/17, 4/2, 4/4, 4/10, 4/15, and 4/20).

To monitor FGH’s recovery, we compared her lowest daily Druid score to her baseline score on those days when she completed 2, 3, or 4 tests, which indicated the best score she was capable of producing each day. Figure 1 reports these test results. Due to the idiosyncratic daily variability of her scores, we did not include data from days in which only one test score was recorded. From March 2 through April 21, for example, her daily scores spanned a range of 5.0 points or greater on 15 days, with a one-day maximum range of 11.0.

As noted above, when experienced users are unimpaired and can complete the test without becoming distracted, Druid’s test-retest reliability is quite high, with successive tests typically varying by a mean absolute value of 0.89 points (SD= 0.71). The variability of FGH’s daily scores may be a manifestation of her clinical status but in counterpoint, it is important to note that her single-day scores spanned a range of 5.0 points or greater on three of her final six testing days when her lowest daily score was near or below her baseline score, indicating minimal or no impairment.

Results

On January 23, three days after her fall, FGH’s lowest daily Druid score was 57.4 (baseline + 23.6 points), indicating severe impairment due to her concussion. As shown in Figure 1, her score peaked at 62.5 (baseline + 28.7 points) on January 31, 11 days following her accident. In time, her scores began to improve steadily through February 15 when her lowest daily score was only 36.9 (baseline + 3.1 points). Based on this score, FGH formed a personal impression that she had fully recovered and decided on her initiative to discontinue the testing regimen, as reported in Table 2 along with other key events.

Beginning in mid-February, as the workplace training program proceeded, FGH gradually took on expanded duties at the center. First, she became responsible for setting up the dialysis machines first thing in the morning, usually arriving 30 minutes early (very often at 3:30 a.m.) to make sure the equipment was ready on time. Next, she was assigned to cannulate patients and connect them to the dialysis machines for their 4-hour treatment. FGH studied her training materials during that time, after which she assisted with disconnecting the patients and deep cleaning the dialysis machines and patients’ chairs.

She resumed her Druid testing routine on March 2 in anticipation of her medical follow-up appointment the next day. She continued testing through March 6. Her lowest daily scores on those days ranged between 38.1 (baseline + 4.2 points) and 42.7 (baseline + 8.8 points), which was her test score on March 2. We alerted her on March 10 that even though she had been medically cleared on March 3 to resume her normal activities, her impairment scores were still well above her baseline and that she should resume her daily testing routine until her tests indicated her cognitive and motor functioning was normal for several days in a row.

Over the next few weeks, FGH gradually worked up to assuming full responsibility for treating the dialysis patients. The staff checks in with the patients as they receive treatment and responds to emergencies (e.g., loss of consciousness, severe bleeding) but otherwise sits at a computer to monitor the patients and make chart entries every half hour. Thus, by degrees, FGH spent more and more time sitting at a computer, and her 11-hour shifts became much more physically demanding, mentally taxing, and subjectively stressful. Ultimately, she became capable of working on her own, managing several patients at a time. Figure 1 shows that her lowest daily Druid scores during this time were substantially above her baseline, indicating significant impairment. On March 21, her lowest daily Druid score peaked at 44.8 (baseline + 11.0 points).

Beginning on April 4, FGH began intensive preparation for a mandatory certification examination on April 14. Thus, her work shift for April 4-7 and April 10-13 was reduced to five hours, from 8:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. While at work, she sat in the dialysis center’s windowless back office where she watched several live presentations online (which she described as “staring at a screen all day”) and worked through a study guide notebook. Anxious about the exam, she continued to study after hours and on the weekend. On April 11, she emailed us to report that she had not been feeling well the past week, with “lots of headaches and dizziness,” and expressed concern about her concussion recovery. On April 14, her lowest daily Druid score again peaked at 44.8 (baseline + 11.0 points).

FGH passed the exam on April 14 and after a weekend of rest, she returned to her regular work schedule the following Monday, April 17. We instructed her to discontinue her testing regimen after her lowest daily scores were close to or below her baseline for six days in a row. This occurred from April 23 through April 28, roughly three months after her injury, with her lowest daily scores ranging from 30.1 (baseline – 3.7 points) to 36.3 (baseline + 2.5 points).

Discussion

The Druid impairment assessment app performed as expected. After falling and suffering a concussion, patient FGH’s lowest (best) daily Druid scores on the 1-minute Druid Rapid test were dramatically higher, on one day peaking at 28.7 points above her baseline. In time, her scores began to fall (improve) steadily as her recovery progressed until her score was only 3.1 points above baseline.

Importantly, FGH’s scores went up again after her workplace training program began to present increasing physical demands, screen time, and stress. It was in this context that she received medical clearance to resume her normal activities. A key finding is that around this time, her lowest daily Druid scores were elevated once again.

As her training program continued, FGH gradually took on more duties and eventually assumed full responsibility for the dialysis patients. Her 11-hour shifts were physically and mentally draining and she spent several hours sitting at a computer. During this time, her lowest daily Druid scores were substantially higher, on one day exceeding her baseline score by 11.0 points. Later, when she began intensive preparation for her certification exam, she spent five hours per day in a back room to watch online presentations and work through a study guide notebook and then continued to study after hours and on the weeken d. During this stressful time, she reported experiencing headaches and dizziness. As before, her lowest daily Druid score peaked at 11.0 points above her baseline.

Following the exam and after a weekend of rest, FGH resumed her regular duties at the dialysis center. Three months after her accident, her lowest daily Druid scores eventually decreased until they were slightly above or below her baseline score for six consecutive days. Those results suggest that FGH’s impairment had resolved, suggesting that she had fully recovered from her concussion.

FGH’s experience showed that the best testing regimen is three consecutive Druid Rapid tests each day, which together could take as little as four or five minutes. This needs to be verified in a future study with several high-risk participants (e.g., athletes, first responders) who could be asked to pre-establish their baseline scores, some percentage of whom will experience an eventual concussion.

FGH’s daily Druid scores were often quite variable, making it necessary to use her lowest (best) daily score as the key indicator rather than an average score. There was no apparent relationship between the scores’ daily variability and her lowest daily scores. Future research should also examine whether other concussion patients will likewise produce highly variable scores, as well as whether for some patients, a decrease in this variability might be an additional indicator of their progress toward recovery.

For daily monitoring, an important advantage of Druid Rapid over other computerized concussion assessment tools is its simplicity and brevity. In contrast, the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB; Cambridge Cognition, Cambridge, England) takes approximately 35 minutes to administer and is not appropriate for use at home [10]. Immediate Post-Concussion and Cognitive Testing (ImPACT) is a concussion assessment and management tool that can be taken at home using a computer with an internet connection but takes approximately 20 minutes to complete (ImPACT Applications, Calgary, Alberta, Canada) and has inconsistent test-retest reliability [11].

Other assessment methods require far less time but have other limitations. The King-Devick test of rapid number naming (King-Devick Technologies, Downers Grove, Illinois, USA), which is used for sideline testing of athletes, can be completed in approximately 2 minutes but is not self-administered [12]. The BioEye app is a newly developed 1-minute test that assesses multiple ocular biomarkers to assess changes in brain function due to concussion (BioEye, Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia); it is not self-administered and requires additional evaluation research [13].

There are other mobile apps available to promote self-management of concussions that provide extensive information about concussions, symptom management, and other resources as well as extensive testing feedback – e.g., AHS Concussion Connection (Alberta Health Services, Edmonton, Canada); Concussion Tracker (Complete Concussion Management, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). Ironically, a potential disadvantage of such apps is their comprehensiveness, as “engaging with mobile technology for sustained periods could aggravate concussion-related symptoms” [14]. With Druid, in contrast, users are told their new impairment score but accessing more detailed information about their test requires opening additional screens.

These findings demonstrate Druid Rapid’s potential to serve as a simple, fast, inexpensive, and user-friendly tool that professionally diagnosed concussion patients can use each day at home or elsewhere to monitor their recovery progress. Importantly, a series of elevated Druid impairment scores may signal that patients should adjust their activity level, screen time, and sleep schedule, or take other remedial or rehabilitative steps to expedite their recovery, or in some cases, consult with their healthcare provider. Future research will examine Druid’s utility for daily monitoring of concussion recovery among athletes, first responders, and other populations.

Conclusion

This case report demonstrates the Druid impairment assessment app’s potential to serve as a simple, fast, inexpensive, and user-friendly tool that concussion patients can use each day to monitor their recovery progress. Elevated impairment scores may signal that patients should adjust their activity level, screen time, and sleep schedule, or take other remedial or rehabilitative steps to expedite their full recovery. Future research will examine Druid’s utility for daily monitoring of concussion recovery among athletes, first responders, and other populations.

Funding

No external funding supported this study.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Dr. James Wesdock and Rob Schiller, JD, for their careful reading of our previous draft and their insightful comments and recommendations.

Conflicts of interest

The following individuals are affiliated with Impairment Science, Inc., which developed the Druid impairment assessment app, and hold stock and/or stock options in the company: William DeJong, Advisory Board; Peter W. Choo, Advisory Board; Isabella M. Stanley, Research Assistant; and Michael A. Milburn, Founder, Chief Science Officer, Board of Directors.

References

- Pearce AJ, Tommerdahl M, King DA (2019) Neurophysiological abnormalities in individuals with persistent post-concussion symptoms. Neuroscience 408: 272-281. [Crossref]

- Ketcham CJ, Hall E, Bixby WR, Vallabhajosula S, Folger SE, et al. (2014) A neuroscientific approach to the examination of concussions in student-athletes. J Vis Exp 8: 52046. [Crossref]

- Rier L, Zamyadi R, Zhang J, Emami Z, Seedat ZA, et al. (2021) Mild traumatic brain injury impairs the coordination of intrinsic and motor-related neural dynamics. Neuroimage Clin 32: 102841. [Crossref]

- Scorza KA, Cole W (2019) Current concepts in concussion: Initial evaluation and management. Am Fam Physician 99: 426-434. [Crossref]

- Richman J, May S (2019) An investigation of the Druid® smartphone/tablet app as a rapid screening assessment for cognitive and psychomotor impairment associated with alcohol intoxication. Vis Dev Rehabil 5: 31-42.

- Spindle TR, Martin EL, Grabenauer M, Woodward T, Milburn MA, et al. (2021) Assessment of cognitive and psychomotor impairment, subjective effects, and blood THC concentrations following acute administration of oral and vaporized cannabis. J Psychopharmacol 35: 786-803. [Crossref]

- Karoly HC, Milburn MA, Brooks-Russell A, Brown M, Streufert J, et al. (2022) Effects of high-potency cannabis on psychomotor performance in frequent cannabis users. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res 7: 107-115. [Crossref]

- Tipton MJ, Harper A, Paton JF, Costello JT (2017) The human ventilatory response to stress: Rate or depth?. J Physiol 595: 5729-5752. [Crossref]

- Barlow P (2012) A practical review of the Glasgow Coma Scale and Score. Surgeon 10: 114-119. [Crossref]

- Arkell TR, Manning B, Downey LA, Hayley AC (2023) A semi-naturalistic, open-label trial examining the effect of prescribed medical cannabis on neurocognitive performance. CNS Drugs 37: 981-992. [Crossref]

- Gaudet CE, Konin J, Faust D (2021) Immediate post-concussion and cognitive testing: Ceiling effects, reliability, and implications for interpretation. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 36: 561-569. [Crossref]

- Galetta KM, Liu M, Leong DF, Ventura RE, Galetta SL, et al. (2015) The King-Devick test of rapid number naming for concussion detection: Meta-analysis and systematic review of the literature. Concussion 1: CNC8. [Crossref]

- den Hollander S, Gouttebarge V (2023) Headers and concussions in elite female and male football: A pilot study. S Afr J Sports Med 35: 1-6. [Crossref]

- Ahmed OH, Pulman AJ (2013) Concussion information on the move: The role of mobile technology in concussion management. J Community Inform 9: e3171.