Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) effects about 100, 000 people in the US as per Center for Disease Control [1]. The clinical course of the SCD has been well documented over the years. Major SCD manifestations include acute chest syndrome, pulmonary hypertension, splenic sequestration, renal hypertrophy and possible end-stage renal disease, osteonecrosis, retinitis proliferans, and chronic leg ulcers [2]. The pathophysiology underlying these manifestations includes polymerization of the hemoglobin S (HbS) due to various triggers leading to impaired deformability of the erythrocytes, which get lodged in the post-capillary venules. Multiple recurrences of this key pathophysiological mechanism along with the other biochemical processes leads to the vaso-occlusive crisis and other long-term manifestations [2].

The patients experiencing a vaso-occlusive crisis usually present to the emergency room due to severe pain either in the chest, abdomen or other parts of the body [3]. Most of these patients recover well with pain medication, hydration, supplemental oxygen, and behavioral therapy [4]. But, in patients who present with abdominal pain atypical of their usual sickle cell crisis pain or in those whom the pain doesn’t subside with the above treatment strategies, the possibility of an acute surgical abdomen should be strongly suspected [5]. The surgical conditions could be common conditions like acute appendicitis, cholecystitis or rare ones like ischemic colitis [5]. But, mesenteric ischemia is even rarer with only three cases being reported in the literature so far [6-8].

Case presentation

Our patient was a 56-year-old African-American lady with a history of sickle cell disease, who came into the emergency room with about twelve hours history of abdominal pain, associated with nausea and vomiting. She stated that the pain was sudden in onset with no plausible inciting factors and different from the character of her usual sickle cell crisis, which manifests around six times per year. The pain was non-radiating and there were no aggravating or relieving factors. Her last bowel movement was on the day before the presentation. She had significant past medical history including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, Raynaud’s phenomenon, transient ischemic attack, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and hyperthyroidism. Her medications at the time of admission included Aspirin (325 mg), Folic Acid, Losartan, Hydrocodone-Acetaminophen, Pravastatin, Verapamil, Alprazolam. Her surgical history included tubal ligation, caesarian section and hysterectomy. She did not have a history of bowel obstruction.

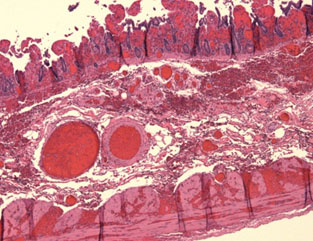

On examination, the patient was afebrile, and other vital signs were within normal limits. She was alert and oriented and answering questions appropriately. Her abdominal examination was significant for diffuse tenderness and positive peritoneal signs. Bowel sounds were hypoactive. Immediate treatment included pain medication and intravenous fluids for hydration. Lab results were significant for hemoglobin of 17.5 g/dl, white blood cell count of 13.2K with a left shift, serum lactate of 7.1, anion gap of 12 (See table 1). Given the concerning physical examination, CT angiogram of the abdomen and pelvis was also ordered, which showed evidence of ascites, dilated small bowel with transition point in the right lower quadrant, and paucity of blood flow in some of the right sided branches of superior mesenteric artery (Figure 1). As the findings were concerning for mesenteric ischemia, patient was emergently transferred to the operating room (OR) for an exploratory laparotomy. A dose of piperacillin – tazobactam was given before the OR.

Table 1. Lab values at the time of emergency room visit

LAB |

VALUE (Normal Range) |

Hemoglobin |

17.5 (10.9 - 15.6 g/dl) |

Hematocrit |

54.1 (31.0 - 47.0%) |

WBC |

13.2 (3.3 - 11.5 K/mcl) |

Granulocytes % |

88 (30.0 - 60.0%) |

Absolute Neutrophil Count |

11.7 (1.5 - 6.6 K/mcl) |

Lymphocytes % |

6.4 (30.0 - 40.0%) |

Monocytes % |

4.5 (2.0 - 9.0%) |

Eosinophils % |

0.0 (0.0 - 7.0%) |

Basophils % |

0.1 (0.0 - 3.0%) |

Platelets |

277 (150 - 450 K/mcl) |

Lactate |

7.9 (0.5 - 2.2 mmol/L) |

Glucose |

159 (70 - 125 mg/dl) |

Blood Urea Nitrogen |

19 (7 - 26 mg/dl) |

Creatinine |

1.0 (0.5 - 1.5 mg/dl) |

Sodium |

145 (135 - 145 mmol/L) |

Potassium |

3.8 (3.5 - 5.0 mmol/L) |

Chloride |

114 (98 - 112 mmol/L) |

Bicarbonate |

19 (22 - 32 mmol/L) |

Albumin |

3.1 (2.8 - 5.5 mmol/L) |

Alanine Transaminase |

39 (0 - 49 U/L) |

Aspartate Transaminase |

24 (0 - 39 U/L) |

Total Bilirubin |

0.3 (0.1 - 1.6 mg/dl) |

Alkaline Phosphatase |

48 (38 - 126 U/L) |

Lipase |

109 (0 - 200 U/L) |

Figure 1. Less well-opacified mesenteric branches on the right side.

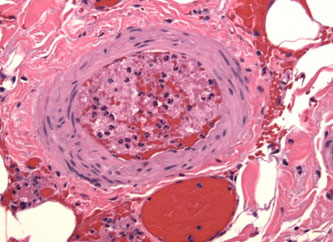

In the OR, hemorrhagic ascites was encountered upon entering the abdomen. Starting from the ileocecal junction 250cm of small bowel was found to be gangrenous (Figure 2). The small bowel proximal to this was pink, with good peristaltic movements, and the mesenteric branches supplying to the bowel also had good pulsations. The gangrenous part of ileum was resected, and a stapled ileocecal anastomosis was performed. Partial cecectomy and appendectomy were also performed. A Jackson-Pratt drain was left at the site of anastomosis. The patient was extubated and then transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU).

Figure 2. Intraoperative photo showing necrotic small bowel.

Post-operatively the patient was kept nil per oral (N.P.O) with a nasogastric tube in place and was on Vancomycin and piperacillin – tazobactam. She complained of chest pain post-operatively for which troponins were ordered and trended. The Troponin-I increased from 0.153 ng/ml to 0.707 ng/ml by postoperative day one (POD#1). Cardiology evaluation had attributed this to demand ischemia and a beta-blocker was started. On POD#2, the Troponin-I peaked at 0.858 ng/ml and subsequently trended down. The patient was transferred to the floor. On POD#3, patient started passing flatus and had a bowel movement. On POD#4, nasogastric tube was removed, and a clear liquid diet was started. Diet was advanced as tolerated and the patient was discharged to home on POD#7 in a stable condition.

Pathology

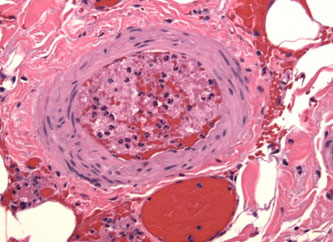

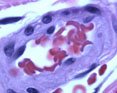

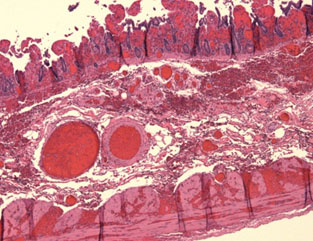

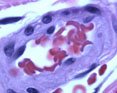

Gross examination reveals a resected segment of small bowel specimen with diffuse dark red discoloration, distension and mesentery hemorrhagic changes and thrombosis in mesentery arteries. The bowel wall shows no evidence of perforation. Microscopically, the small intestine exhibits transmural necrosis, hemorrhagic changes and edema Figure 3A). Fresh and partial organized thrombosis noted in mesentery arteries and arterioles (Figure 3B). The patient’s erythrocytes in microvascular bed are disformed in sickle shape (Figure 3 insert). The morphological features support the diagnosis of vessel-occlusive ischemic necrosis of ileum secondary to sickle cell disease induced mesentery arterial thromboembolism.

Figure 3. 3A. Transmural ischemic necrosis of small intestine;

3B. Arterial thrombosis of small intestine;

3B insert: Sickle-shaped red blood cells in mesentery arteriole.

Discussion

A comprehensive literature review was conducted using PubMed with the key words sickle cell crisis and ischemic bowel. There are a few studies and case reports about ischemic bowel secondary to the vaso-occlusive crisis. Majority of the case reports have been about ischemic colon [9-14]. And the retrospective studies that have looked at the effect of vaso-occlusive crisis on gut vasculature have also noted that colon is the more frequently affected part of the intestine [15,16]. This further underline the rarity of mesenteric ischemia in this subset of patients.

Mesenteric ischemia can be caused by arterial occlusion from embolus/thrombus, non-occlusive low flow state, or venous thrombosis [17]. Of these, ischemia due to arterial occlusion is the most common etiology. In SCD the vaso-occlusion usually occurs due to trapping of the sickle cells in the post-capillary venules [18]. The histopathological findings in our case are consistent with the literature that the crisis occurs due to the occlusion of the vasculature by deformed red blood cells. But, it is interesting to see in our case that there is arterial arteriolar thrombosis secondary to the sickle cell occlusion which has not been as widely reported in the literature as post-capillary venular thrombosis. Transmural necrosis with edema and hemorrhagic changes are consistent with the findings reported in the other case reports [6,8,10,12,13]. Mucosal ulcerations have also been reported, which is probably due to longer duration of ischemia [6,10,12].

Low flow state can further aggravate the sickle cell crisis as seen in the case report by Hammond et al [7]. Hypotension was due to vasodilator therapy the patient was on for pulmonary hypertension. Hypoxia due to the pulmonary hypertension and sickle cell crisis on top of a hypotensive episode precipitated the fatal mesenteric ischemia.

Typical vaso-occlusive crisis symptoms such as acute chest syndrome and leg pains can be confounding factors when present along with the abdominal pain. During the hospital admission other symptoms might get better but, abdominal pain might fail to resolve and get worse due to worsening underlying ischemia. This seems to have been the issue in the case reports by Gage et al., Karim et al., Green et al., and Qureshi et al [10-13]. In all those patients, the abdominal symptoms got worse during the hospital course and they were ultimately diagnosed with ischemic colitis.

The diagnosis of a surgical abdomen can be more tricky in sickle cell patients who are on peritoneal dialysis as seen in the case report by Engelhardt et al [6]. Presence of ascitic fluid might not have been as concerning a feature as it would be in our patient. Their patient was initially thought to have peritoneal dialysis associated peritonitis and was started on antibiotics first. Over the course of next 72 hours patient’s abdominal pain worsened, abdominal became distended and peritoneal signs were positive, for which the patient was taken to the OR, where 35 cm of terminal ileum was found to be necrotic. CT scan was not done on their patient, which might have delayed the diagnosis.

To avoid morbidity and mortality, it is best to diagnose these cases as soon as possible. A patient with a known history of sickle cell crisis who states that the abdominal pain is different from his/her usual crisis pain should be thoroughly investigated for causes that might need surgical attention. In this process, the paramount importance of a good history and physical examination goes without saying. Our patient had signs of peritonitis which is not something one would expect in sickle cell crisis. Also, non-resolution of abdominal pain with standard treatment or development of new abdominal signs and symptoms can be an ominous sign.

When clinical features do not seem to point towards sickle cell crisis it is always prudent to go for an ultrasound abdomen or a CT scan based on the presentation. CT signs of ischemic bowel like bowel wall thickening, mesenteric stranding, free fluid in the abdomen, target sign should all ring alarm bells [15,16]. The clinicians should have a high degree of suspicion for ischemic bowel especially in sickle cell patients who do not fit the picture of sickle cell crisis, acute appendicitis, cholecystitis or pancreatitis. Early diagnosis is the key to best outcomes.

References

- Prevention (2017) CfDCa. Sickle Cell Disease.

- Marie J Stuart RLN (2004) Sickle-cell disease. The Lancet. 364: 1343-1360.

- Yusuf HR, Atrash HK, Grosse SD, Parker CS, Grant AM (2010) Emergency Department Visits Made by Patients with Sickle Cell Disease: A Descriptive Study, 1999–2007. Am J Prev Med 38: S536-S541. [Crossref]

- Rees DC, Olujohungbe AD, Parker NE, Stephens AD, Telfer P, et al. (2003) Guidelines for the management of the acute painful crisis in sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol 2003. 120(5): p. 744-752. [Crossref]

- Ahmed S, Shahid RK, Russo LA (2005) Unusual causes of abdominal pain: sickle cell anemia. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 19: 297-310. [Crossref]

- Engelhardt T, Pulitzer DR, Etheredge EE (1989) Ischemic intestinal necrosis as a cause of atypical abdominal pain in a sickle cell patient. J Natl Med Assoc 81: 1077-1088. [Crossref]

- Hammond TG (1989) Fatal small-bowel necrosis and pulmonary hypertension in sickle cell disease. Archives of Internal Medicine 149: 447-448.

2021 Copyright OAT. All rights reserv

- Abadin SS, Salazar MR, Zhu RY, Connolly MM, Podbielski FJ (2009) Small Bowel Ischemia in a Sickle Cell Patient. Case Rep Gastroenterol 3: 26-29. [Crossref]

- van der Neut FW, Statius van Eps LW, van Enk A, van de Sandt MM (1993) Maternal death due to acute necrotizing colitis in homozygous sickle cell disease. Neth J Med 42: 132-1323. [Crossref]

- Gage TP, Gagnier JM (1983) Ischemic colitis complicating sickle cell crisis. Gastroenterology 84: 171-174. [Crossref]

- Green BT, Branch MS (2003) Ischemic colitis in a young adult during sickle cell crisis: case report and review. Gastrointest Endosc 57: 605-607. [Crossref]

- Karim A, Ahmed S, Rossoff LJ, Siddiqui R, Fuchs A (2002) Fulminant ischaemic colitis with atypical clinical features complicating sickle cell disease. Postgrad Med J 78: 370-372. [Crossref]

- Qureshi A, Lang N, Bevan DH (2006) Sickle cell 'girdle syndrome' progressing to ischaemic colitis and colonic perforation. Clin Lab Haematol 2006. 28: 60-62. [Crossref]

- Moukarzel AA, Rajaram M, Sundeep A, Guarini L, Feldman F (2000) Sickle cell anemia: severe ischemic colitis responding to conservative management. Clinical Pediatrics 39: 241-243. [Crossref]

- Gardner CS, Jaffe TA (2015) CT of Gastrointestinal Vasoocclusive Crisis Complicating Sickle Cell Disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol 204: 994-999. [Crossref]

- Gardner CS, Jaffe TA (2016) Acute gastrointestinal vaso-occlusive ischemia in sickle cell disease: CT imaging features and clinical outcome. Abdom Radiol 41: 466-475. [Crossref]

- Mastoraki A, Mastoraki S, Tziava E, Touloumi S, Krinos N, et al. (2016) Mesenteric ischemia: Pathogenesis and challenging diagnostic and therapeutic modalities. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 7: 125-130. [Crossref]

- Kaul DK, Fabry ME, Nagel RL (1996) The pathophysiology of vascular obstruction in the sickle syndromes. Blood Rev 10: 29-44. [Crossref]