The objective of this ‘1 of 3’ mini-series is to highlight the place of infection in maternal mortality and with a view to draw attention on possibility of infectious control perspective. This seminar paper presents an overview of maternal mortality in Nigeria, followed by trends, causes and effects. Of interest, the causes highlight the contribution of infection while discussion of the effects touches on child death. Finally, the brief discussion focuses on maternal and child health.

Type 2 diabetes, self-monitoring, blood glucose

Maternal mortality rate is one of the indicators of health discrepancies between developed, underdeveloped and developing countries. Nigeria is one of the countries in Sub-Saharan Africa where maternal mortality has remained a problem. The country’s progress towards reducing the number of maternal deaths has been largely insufficient. Maternal mortality persists in Nigeria despite strategies like the promotion of institutional deliveries, training and deploying new skilled health workers. It is also among the top six countries in the world that contribute to more than 50% of all global maternal deaths [1].

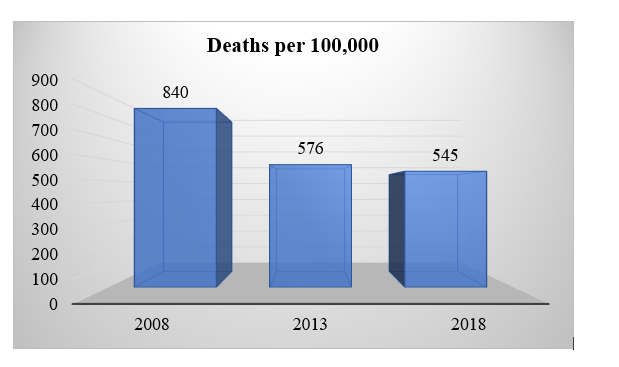

In 2008, Nigeria had the second largest recorded number (50,000) of maternal deaths with an estimated maternal mortality rate of 840/100,000 live births. The Nigeria Demographic and Health Surveys (NDHS) revealed a gradual decline in national maternal mortality rate in 2013 and 2008 (Figure 1). However, studies have shown that the levels of maternal mortality vary within the country. There are states and health facilities that have higher levels of maternal mortality compared to the national average [2]. For instance, some northern states like Kano in 2008 had a maternal mortality rate of 1600 deaths per 100,000 live births while 1049 deaths per 100,000 live births were reported in Zamfara state. Also, health facilities show similarly high levels of maternal mortality with 927 deaths per 100,000 live births reported for 21 health facilities in three states - Katsina (North), Lagos (South) and the Federal Capital territory (North).

Figure 1: Mortality rates reported in between 2008 and 2018.

Trends of maternal mortality in Nigeria

Nigeria consists of six geo-political zones: the North, North West, North Central, North East; and in the South, South East, South-South and South West. The National Population commission of Nigeria shows the North and South as two distinct regions. They are different in terms of educational levels attained, utilization of health facilities and other cultural influences like the prevalence of polygamy. These factors are linked with health outcomes such as maternal mortality. Women in the North are less likely to give birth at health faciliities and many in some northern states, live far from health centres which are plagued by severe shortages of health workers compared to the South of Nigeria [2]. However, data from the WHO show gradual decline nationally (Table 1).

Table 1: 18 years’ historical data of Nigeria’s maternal mortality rate [1].

Year |

Per 100K Live Births |

Annual % Change |

2000 |

1,200.00 |

0.00% |

2001 |

1,200.00 |

0.00% |

2002 |

1,180.00 |

-1.67% |

2003 |

1,170.00 |

-0.85% |

2004 |

1,130.00 |

-3.42% |

2005 |

1,080.00 |

-4.42% |

2006 |

1,040.00 |

-3.70% |

2007 |

1,010.00 |

-2.88% |

2008 |

996.00 |

-1.39% |

2009 |

987.00 |

-0.90% |

2010 |

978.00 |

-0.91% |

2011 |

972.00 |

-0.61% |

2012 |

963.00 |

-0.93% |

2013 |

951.00 |

-1.25% |

2014 |

943.00 |

-0.84% |

2015 |

931.00 |

-1.27% |

2016 |

925.00 |

-0.64% |

2017 |

917.00 |

-0.86% |

This gradual decline may also be related to the introduction of free maternal health care including antenatal services by some State governments. For instance, a report from the Southern Niger-Delta region highlighted three factors (antenatal registrations, births at hospitals and qualified healthcare professional on service) as key improvements that are attributable to the observed decline in maternal mortality rate [3].

Causes of maternal mortality

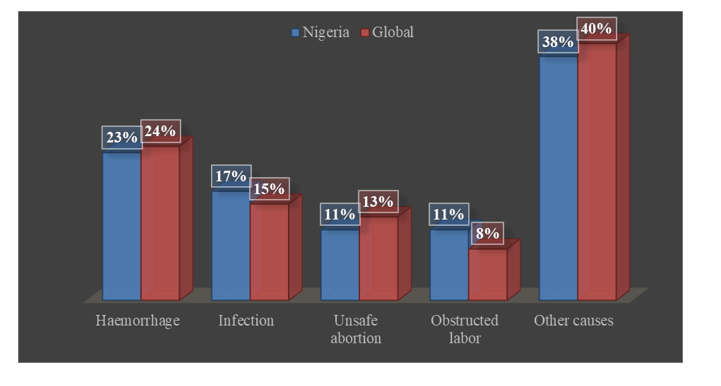

The aetiology of maternal mortality can be categorized as medical, socio-economic, cultural, behavioural, and political causes. The medical causes are the simplest to determine and describe. Several articles identified major causes of maternal mortality that are consistent with worldwide data; 70 percent of maternal deaths in Nigeria are due to one of five complications: haemorrhage, infection, unsafe abortion, hypertensive diseases of pregnancy such as eclampsia, and obstructed labour (Figure 2). While some of the occurrences are predicted during routine prenatal care, most occur spontaneously without warning signs and constitute high risk pregnancies.

Figure 2: Showing global causes of maternal mortality [5,6].

Therefore, all pregnant Nigerian women should be considered at risk of these complications. High risk in pregnancy may be predicted in women during prenatal care if they have high blood pressure, gestational diabetes mellitus, pre-term rupture of the membranes, gestation of greater than 42 weeks, or vaginal bleeding amongst others. Further, common determinants of high-risk pregnancies in Nigeria including age over 35 years, anaemia and infections are top-of-the-list contributors to maternal deaths. The majority of the published journal articles were based in institutions and hospitals and may exclude examination of death during at-home deliveries [4].

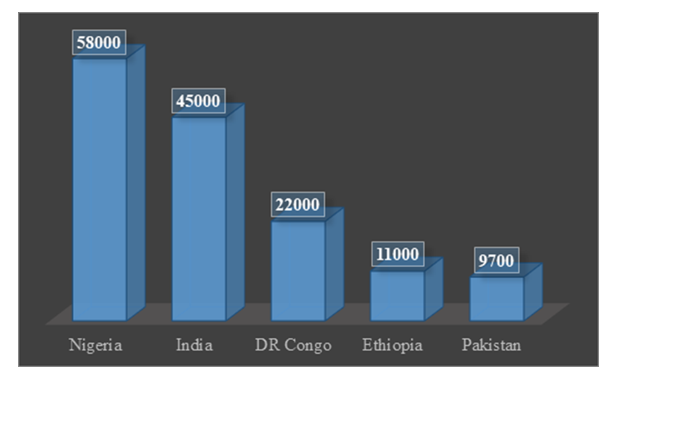

It is pertinent to note that Nigeria was depicted to have the highest maternal mortality rate in a 2013 report (Figure 3). Therefore, despite the positive trend of decline, it is still imperative to review the factors that influence maternal mortality rate in Nigeria.

Figure 3: Maternal mortality in Nigeria vs. some other countries [7].

Maternal mortality served as an issue in the developing countries which has caught global attention since late 1990s by placement in the MDGs as mentioned above [8]. However, this issue persists in developing countries and the recent efforts in the shape of SDGs have also placed the issue. To eliminate the issue of maternal mortality or to reduce it requires better understanding of its underlying causes.

There have been several factors which contribute towards the severity of MMR specifically in the developing countries which mainly include medical causes. Among the medical causes is the concept of ‘3 delays’ including delay in seeking, receiving and reaching care [9]. This concept identifies that a woman’s awareness (knowledge to seek) is one factor, but the accessibility (i.e., ability to reach) to healthcare facility as well as equity and quality (receiving prompt attention) service all come as a package. Perhaps, what needs to be highlighted is this package can come in primary healthcare.

Therefore, understanding and identifying the causes are more important to reducing the maternal mortality rates and saving the life of women. In Nigeria, the concept of 3-delays is seen in incomplete and/or insufficient utilization of antenatal care [10,11]. These factors can be divided broadly into three categories of socio-cultural, economic, and political. Any improvement in how these factors influence primary healthcare will translates into improvements in the reduction of maternal mortality [8].

Effect of maternal mortality

The effects of maternal mortality on socioeconomic development cannot be overemphasised. Maternal mortality which in most cases is attributable to low level of socioeconomic status is also a major factor hindering sustainable development. Maternal mortality remains a major indicator used in measuring the level of development of a society and the performance of the healthcare delivery system [12]. For instance, it is a given that maternal mortality remains the focus of maternal-and-child health developmental agenda in sub-Saharan Africa countries (Table 2).

Table 2: Effects of maternal mortality on children, families and society[13, 14].

Potential effects |

Children |

Families |

Society |

Demographic |

Death |

Loss of deceased

Dissolution or reconstitution of family/household |

Loss of deceased

Increased number of one parent households

Increased number of orphans |

Economic |

Increased labour force participation |

Reduced productivity of the sick

Lost productivity of deceased adults

Financial stress from medical costs |

Reduced productivity

Lost output of deceased adult

Economic burden of disease

|

Health |

Illness

Injury

Malnutrition

Poor hygiene |

Reduced allocation of labour to health maintaining activities

Poor health for surviving household members |

Change in the allocation of labour to health activities |

Psychological |

Depression

Other psychological problems |

Depression

Other psychological problem

Grief loved ones |

Grief

Loss of community cohesion |

Social |

Social isolation

Reduced education

Reduced parental supervision |

Social Isolation

Changes in care for children, elderly and disabled |

Reduced quality of life

Loss of community

|

Maternal mortality is an issue of local as well as global concern. Several numbers of studies have dealt with the issue of maternal mortality particularly focusing on its associated causes other than the medical ones as the social, cultural and economic across the developing world. However, the issue has not been exhaustively explored at the primary healthcare level in Nigeria with its underlying causes so that the local level measures can be adopted to combat it. As indicated on figure 2, bleeding and infection are the leading causes of maternal mortality.

It has remained a concern that the rate of Nigerian maternal and child deaths during birthing are still relatively high, and preventable childbirth behaviour is one of the factors [15,16]. Another important factor is health promotion buoyed by infrastructural developments that facilitate equitable access to the facilities [15].

Of particular interest in this mini-series is the second leading cause of death – infection. For this paper, focus is on environmental hygiene sanitation practices with regards to maternal and child health (MCH). It is noteworthy that open defecation is a public health menace arguably affecting maternal and child health more. At least, this fact has been the basis of research interests [17-20], as well as global and national intervention programs [21-23].

The agenda for maternal and child health advocacy is that all pregnant women and children in Nigeria regardless of their income, location, religion, or sociocultural group have access to care. The vision of primary healthcare promotion includes to provide education and preventive approaches at the local levels [24]. Recent review has highlighted the limitations of primary healthcare in Bayelsa State [25]. What this paper brings to the fore is the need to consider advancement and integration of hygienic infection control awareness at the primary healthcare level as one preventive medicine measure in management of maternal mortality.

Every effort must be made to provide life-saving interventions for pregnant women to advance improvement in reducing maternal mortality. These interventions may include improving primary healthcare services and systems. Given that infections constitute the second most causative factor i.e. after bleeding, health promotion would necessarily need to consider infection control services such as provision of better hygiene behaviour and sanitary facilities. Thirdly, obstetric services need to be accessible, affordable, and available always so that pregnant women can receive service without any of the “3-delays”.

This was a piece of seminar presentations on contemporary public health issues done as part of academic exercise by POT. First review was by EUN. Second review and articulation were done by OCC.

- WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division (2015) Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2015.

- Meh C, Thind A, Ryan B, Terry A (2019) Levels and determinants of maternal mortality in northern and southern Nigeria. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 19: 417.

- Azubuike S, Odagwe N (2015) Effect of free maternal health services on maternal mortality: An experience from Niger Delta, Nigeria. CHRISMED J Health Res 2: 309-315.

- Piane GM (2019) Maternal mortality in Nigeria: A literature review. World Med Health Policy 11: 83-94.

- Bakare M, Takai UI, Bukar M (2015) Rising trends in maternal mortality at the University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital. Tropical Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2015; 32: 124-131.

- Audu B, Takai U, Bukar M (2010) Trends in maternal mortality at University of Maiduguri teaching hospital, Maiduguri, Nigeria - A five-year review. Nig Med J 51: 147-151.

- Roser M, Ritchie H (2013) Maternal mortality. OurWorldInData.Org.

- Gholampoor H, Pourreza A, Heydari H (2018) The effect of social and economic factors on maternal mortality in provinces of Iran within 2009-2013. Evid Health Policy Manag Econ 2: 80-90.

- Nour NM (2008) An introduction to maternal mortality. Rev Obstet Gynecol 1: 77-81. [Crossref]

- El-Khatib Z, Kolawole Odusina E, Ghose B, Yaya S (2020) Patterns and Predictors of Insufficient Antenatal Care Utilization in Nigeria over a Decade: A Pooled Data Analysis Using Demographic and Health Surveys. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17: 8261. [Crossref]

- Nwose EU, Mogbusiaghan M, Bwititi PT, Adoh G, Agofure O, et al. (2019) Barriers in determining prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus among postpartum GDM: The research and retraining needs of healthcare professionals. Diabetes Metab Syndr 13: 2533-2539. [Crossref]

- Akokuwebe ME, Okafor EE (2015) Maternal health and the implications for sustainable transformation in Nigeria. Res Humanit Soc Sci 5: 1-13.

- Alkema L, Chou D, Hogan D, Zhang S, Moller A, et al. (2016) Global, regional, and national levels and trends in maternal mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the UN Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-Agency Group. Lancet 387: 462-474.

- National Research Council Committee on P (2000) In: Reed HE, Koblinsky MA and Mosley WH (eds) The Consequences of Maternal Morbidity and Maternal Mortality: Report of a Workshop. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US).

- Oladapo OT, Adetoro OO, Ekele BA, Chama C, Etuk SJ, et al. (2016) When getting there is not enough: a nationwide cross-sectional study of 998 maternal deaths and 1451 near-misses in public tertiary hospitals in a low-income country. BJOG 123: 928-938. [Crossref]

- Salawu MM, Afolabi RF, Gbadebo BM, Salawu AT, Fagbamigbe AF, et al. (2021) Preventable multiple high-risk birth behaviour and infant survival in Nigeria. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 21: 345.

- Saleem M, Burdett T, Heaslip V (2019) Health and social impacts of open defecation on women: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 19: 158.

- Azuh DE, Azuh AE, Iweala EJ, Adeloye D, Akanbi M, et al. (2017) Factors influencing maternal mortality among rural communities in southwestern Nigeria. Int J Womens Health 9: 179-188. [Crossref]

- Balogun M, Banke-Thomas A, Sekoni A, Boateng GO, Yesufu V, et al. (2021) Challenges in access and satisfaction with reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health services in Nigeria during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional survey. PloS One 16: e0251382-e0251382. [Crossref]

- Anjorin AAA, Babalola SR, Iyiade OP (2020) Influenza, malaria parasitemia, and typhoid fever coinfection in children: Seroepidemiological investigation in four Health-care Centers in Lagos, Nigeria. J Pan Afr Thorac Soc 1: 26-34.

- UNICEF (2021) UNICEF’s game plan to end open defecation.

- World Health Organization (2012) Water sanitation hygiene - Fast facts: WHO/UNICEF joint monitoring report.

- Ngwu UI (2017) The practice of open defecation in rural Nigeria: A call for social and behavior change communication intervention. Int J Commun Res 7: 201-206.

- Uzochukwu BSC (2017) Primary health care systems (PRIMASYS): Case study from Nigeria.

- Odoko JO, Nwose EU, Nwajei SD (2020) Primary healthcare on utilization of insecticide treated nets among pregnant mothers and carers of children in South–South Nigeria. Clin Med Rev Rep 3.

Editorial Information

Editor-in-Chief

Article Type

Review Article

Publication history

Received date: July 07, 2021

Accepted date: August 01, 2021

Published date: August 05, 2021

Copyright

©2021 Osunu PT. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Citation

Osunu PT, Ofili CC, Nwose EU (2021) Maternal mortality in Nigeria: A consideration of infection control factor. Prev Med Commun Health 4: 10.15761/PMCH.1000158.

Corresponding author

Prof. Uba Nwose

School of Community Health, Charles Sturt University, Orange, Australia

E-mail : bhuvaneswari.bibleraaj@uhsm.nhs.uk