Abstract

Olfactory groove meningiomas are slow-growing tumors that can be extremely insidious because they can grow to gigantic sizes and can be asymptomatic or have subtle symptoms for a long time. These patients are at risk of delaying diagnosis and, consequently, surgical treatment. Visual symptoms may be the only manifestation of the disease and only become apparent when the tumor is very large. With late diagnosis and delayed treatment, compression of the optic nerves can cause fatal and irreversible vision loss.

Objectives: To present a clinical case of a patient with giant meningioma of the olfactory sulcus, in whom the only symptom was progressive vision loss and there was a delay in diagnosis.

Keywords

giant olphactory groove meningioma, visual symptoms, vision loss

Introduction

Meningiomas are primary neoplasms arising from meningeal cells and account for approximately 25%-37% of central nervous system tumors, and more than 80% are located in the cerebral meninges, with half of the cases usually occurring in the parasagittal plane, originating from the falx and convexity, and other common sites being the sphenoid bone, suprasellar region, posterior fossa, and olfactory sulcus [1-3]. Although intracranial tumors generally have a higher incidence in men, meningiomas are found twice as often in women [1,3]. Black race and advancing age are associated with a higher incidence, with the most common median age at diagnosis being 65 years [1,2].

Olfactory groove meningiomas (OGMs) are rare, benign, slow-growing neoplasms of the skull base, accounting for 2% of all primary brain tumors, 4%-18% (according to other authors 8%-13%) of all intracranial meningiomas, and 34% of meningiomas of the anterior fossa [4,5]. Because of their extremely slow growth, many meningiomas are asymptomatic and are discovered incidentally, and the clinical manifestations, when present, are influenced by the location of the tumor and the time it has developed [1], but other factors, such as peritumoral edema and the resulting compression of brain tissue, are also thought to influence the clinical picture [6]. Anosmia is thought to be among the first symptoms of OGM, although patients often complain of headaches or visual problems, and although olfactory dysfunction is a major symptom, it has been poorly studied in these patients and, contrary to expectations, olfactory testing appears to be of little use in detecting olfactory meningiomas [7]. OGM are often associated with cognitive, affective and behavioural deficits, but these symptoms remain poorly understood and personality changes and cognitive impairment may not be apparent until the tumours have become sufficiently large [6,8]. The most commonly affected cognitive functions are those of the prefrontal cortex, particularly those determining cognitive ‘flexibility’ [2]. Psychiatric symptoms have been reported in 14% to 100% of patients, with the most common being memory and attention deficits, confusion and disorientation, and depression, apathy and behavioural changes are also common [8]. Frontal lobe meningiomas are known to cause not only mood changes but also acute psychotic syndromes, therefore they should always be part of the differential diagnosis for both affective and non-affective psychosis [9].

Progressive compression of the frontal lobes and eventual extension into the sella turcica by OGM can compress the optic nerve and optic chiasm, leading to vision loss [10]. Visual symptoms are due to compression of the optic nerves, which can cause edema and eventually progress to atrophy, and may also manifest as Foster-Kennedy syndrome, in contrast to suprasellar meningioma, which elevates the chiasm and thus stretches the cross fibers and causes bitemporal heminopsia and optic nerve atrophy [11]. In summary, the most common symptoms in OGM are headache in 31% to 86%, anosmia (57%–78%), and personality changes (48%–72%), other symptoms may include visual impairment (24%–61%), seizures (17%–35%), or intracranial hypertension in about 50% [5].

Case presentation

We present a clinical case of a 50-year-old woman who visited our neurological practice due to progressive vision loss that began about 2 months ago. Before the neurological examination, the patient had a consultation with an ophthalmologist, who found severely reduced visual acuity bilaterally, with the ability to count fingers, VOD - 0.01, VOS - 0.01. During tonometry, intraocular pressure was measured within normal limits- in the right eye 13 mm Hg, in the left eye 14 mm Hg. Examination of the anterior segment of the eye and the fundus did not show pathological abnormalities, optical coherence tomography also did not detect retinal damage and an examination by a neurologist was recommended. At the first consultation with a neurologist, the patient was not referred for brain imaging and was prescribed outpatient treatment with Vinpocetine 30 mg/d, but due to lack of effect and continued deterioration of vision after one month, the patient visited a neurologist again. The neurological examination revealed severely reduced vision and binasal hemianopsia, the remaining cranial nerves were intact. No paresis of the limbs was detected, tendon reflexes were symmetrical, moderately lively, pathological reflexes were not obtained, coordination was normal. The patient was contact, adequate, bradypsychic and was immediately referred for magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, which revealed an extraaxial frontobasal tumor formation bilaterally (Figures 1-3).

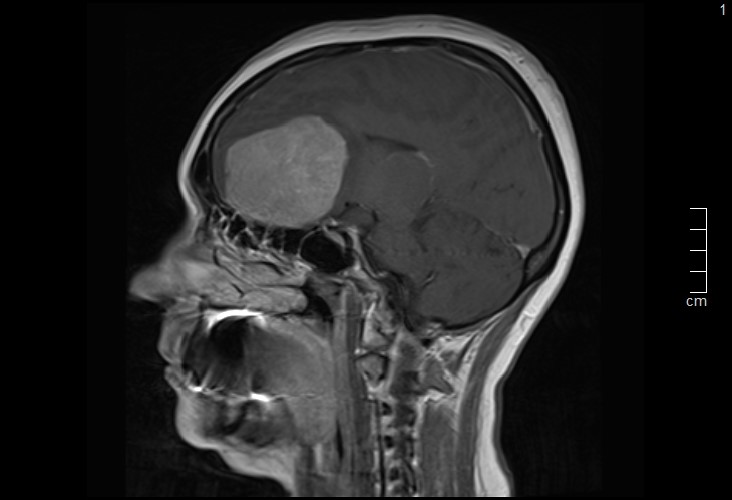

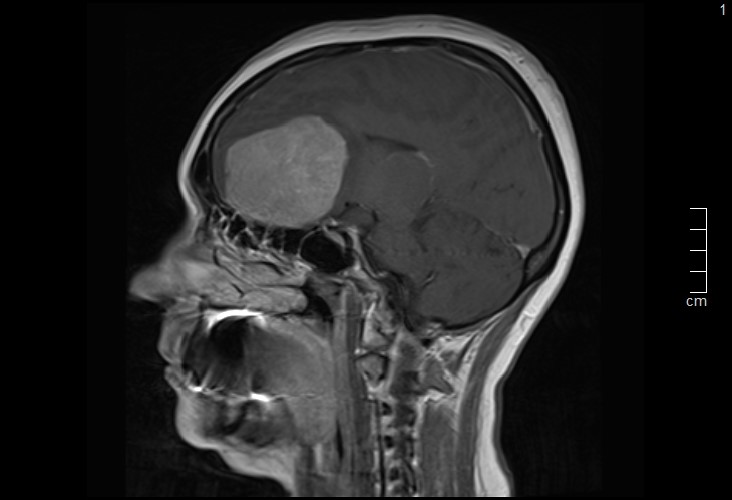

Figure 1. Sagittal T1-weighted contrast-enhanced MRI showing a large, well-defined extraaxial frontobasal mass compressing the frontal lobes, consistent with an olfactory groove meningioma

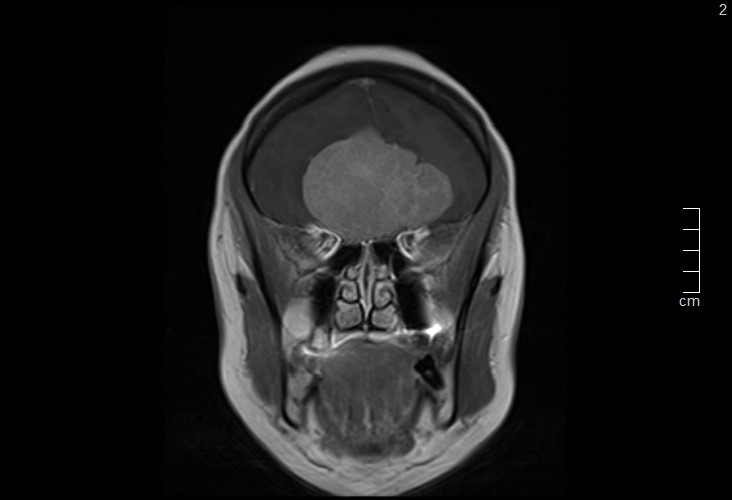

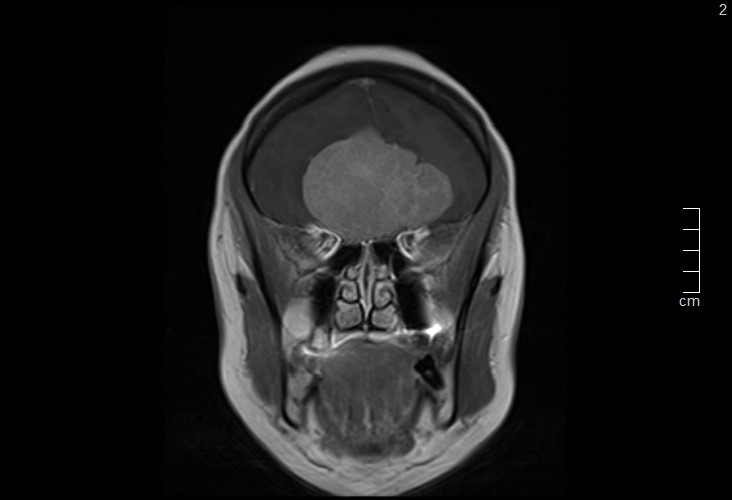

Figure 2. Coronal T1-weighted contrast-enhanced MRI demonstrating a bilateral, dural-based tumor arising from the olfactory groove with midline extension and mass effect on the optic pathways

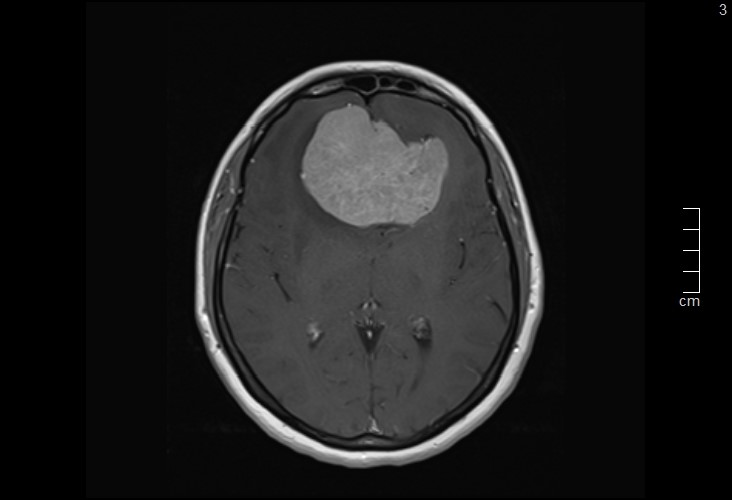

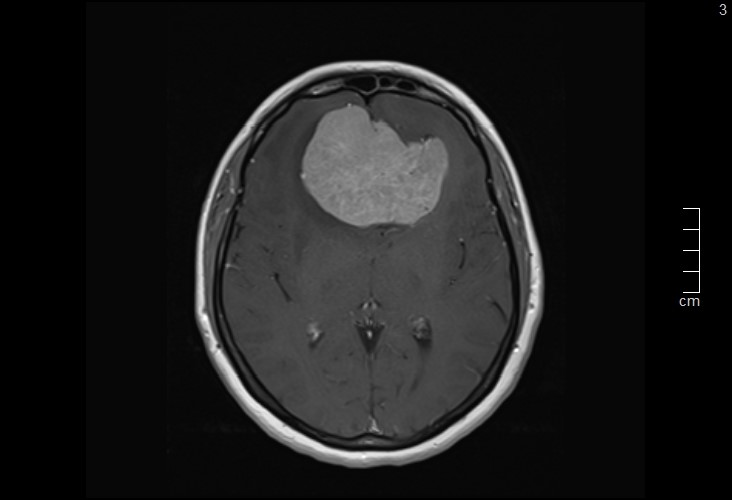

Figure 3. Axial T1-weighted contrast-enhanced MRI revealing a homogeneously enhancing olfactory groove meningioma with significant compression of the frontal lobes

After MRI results and consulting with a neurosurgeon, the patient was referred for surgical treatment to a neurosurgery clinic, where a bifrontal craniotomy was performed with complete removal of the tumor with a macroscopic appearance of an olfactory meningioma. The histological result showed a monomorphic tumor formation composed of spindle-shaped cells forming vortices and single fascicles, without necrosis, atypical cells or increased mitotic activity and the conclusion was that it was a meningotelic meningioma of the I degree according to the WHO. Due to psychotic symptoms, on the 4th postoperative day a consultation with a psychiatrist was performed, who established that the patient was psychomotor restless, showing emotional lability and anxiety, with an accelerated and chaotic thought process and a general decrease in cognitive functions. Sodium valproate was prescribed according to a regimen of up to 1500 mg/d, Hydroxyzine 50 mg/d, Bromazepam 3 mg/d as needed, and outpatient follow-up by a psychiatrist was recommended. When the patient was followed up two months after the operation, there was no improvement in her vision.

Results and discussion

Olfactory sulcus meningiomas are clinically asymptomatic tumors until they reach large size, and due to their location and minimal clinical symptoms, they may remain undetected until symptoms or other abnormalities become apparent [6,11,12]. According to statistics, approximately 3%-12% of patients are diagnosed by incidental imaging in connection with an unrelated symptom [5], and visual symptoms usually occur only after the tumor reaches a significant size [11]. In the presented case, our patient was initially consulted by an ophthalmologist, and the tumor was discovered only during the second neurological examination and after MRI was performed, which resulted in a delay in diagnosis and surgical treatment of more than a month [13-14].

Conclusion

Olfactory sulcus meningiomas are slow-growing tumors that can reach very large sizes before being diagnosed. Visual disturbances are a common manifestation of this type of tumor, and patients with OGM may initially present to an ophthalmologist for ocular symptoms or to a psychiatrist for behavioral and cognitive disturbances. It is important to identify these patients with appropriate imaging studies to avoid fatal delays in treatment.

Conflicts of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Bailo M, Gagliardi F, Boari N, Spina A, Piloni M, et al. (2023) Meningioma and other meningeal tumors. Adv Exp Med Biol 1405: 73-97 [Crossref]

- Dolecek TA, Dressler EV, Thakkar JP, Liu M, Al‐Qaisi A, et al. (2015) Epidemiology of meningiomas post‐public law 107‐206: The benign brain tumor cancer registries amendment act. Cancer 121: 2400-2410. [Crossref]

- Toland A, Huntoon K, Dahiya SM (2021) Meningioma: A pathology perspective. Neurosurgery 89: 11-21. [Crossref]

- Candy NG, Hinder D, Jukes AK, Wormald PJ, Psaltis AJ (2023) Olfaction preservation in olfactory groove meningiomas: A systematic review. Neurosurg Rev 46: 186. [Crossref]

- Ikhuoriah T, Oboh D, Abramowitz C, Musheyev Y, Cohen R (2022) Olfactory groove meningioma: A case report with typical clinical and radiologic features in a 74-year-old Nigerian male. Radiol Case Rep 17: 4492-4497. [Crossref]

- Leo RJ, DuBois RL (2016) A case of olfactory groove meningioma misdiagnosed as schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 77: 67-68. [Crossref]

- Hendrix P, Fischer G, Linnebach AC, Krug JB, Linsler S, et al. (2019) Perioperative olfactory dysfunction in patients with meningiomas of the anteromedial skull base. Clin Anat 32: 524-533. [Crossref]

- Pashkov A, Filimonova E, Poptsova A, Martirosyan A, Prozorova P, et al. (2025) Cognitive, affective and behavioral functioning in patients with olfactory groove meningiomas: A systematic review. Neurosurg Rev 48: 457. [Crossref]

- Jung JJ, Warren FA, Kahanowicz R (2012) Bilateral visual loss due to a giant olfactory meningioma. Clin Ophthalmol 5: 339-342. [Crossref]

- Sulaiman FN, Rajan RS, Halim WH (2023) Visual loss as primary manifestation of olfactory groove meningioma. Cureus 15: e37632. [Crossref]

- Marques JG (2020) Left frontal lobe meningioma causing secondary schizophrenia misdiagnosed for 25 years. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 22: 27473. [Crossref]

- Ciurea AV, Iencean SM, Rizea RE, Brehar FM (2012) Olfactory groove meningiomas: A retrospective study on 59 surgical cases. Neurosurg Rev 35: 195-202. [Crossref]

- Claus EB, Bondy ML, Schildkraut JM, Wiemels JL, Wrensch M, et al. (2005) Epidemiology of intracranial meningioma. Neurosurgery 57: 1088-1095. [Crossref]

- Constanthin PE, Gondar R, Fellrath J, Wyttenbach IM, Tizi K, et al. (2021) Neuropsychological outcomes after surgery for olfactory groove meningiomas. Cancers 13: 2520. [Crossref]