Abstract

Estimation of cardiovascular risk is a need to plan prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Control of hyperlipidemia, besides of other cardiovascular risk factors as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, sedentarism and smoking habit, is the mainstay to lower cardiovascular events. In this review an easy method to calculate this index is shown. Drugs currently in the market are described to decrease blood levels of several lipids: low density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, lipoprotein (a), in order to reach the goals linked to the estimated risk.

Keywords

cardiovascular risk, hyperlipidemia, LDL-cholesterol, lipid-lowering therapy, triglycerides, LP(a)

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD), of which atherosclerotic CVD is the major component, is responsible for >4 million deaths in Europe each year. It kills more women (2.2 million) than men (1.8 million), although cardiovascular (CV) deaths before the age of 65 years are more common in men (490 000 vs.193 000) [1].

The assessment of CV risk has to take into account all known CV risk factors: Age, sex, blood pressure, smoking habit, blood cholesterol levels. Other factors, as diabetes, implies a moderate to very high risk, depending on clinical situation. Factors as obesity, physical inactivity and lipoprotein (a)(LP(a)) levels ≥ 50 mg/dL are considered as risk modifiers after overall CV risk estimation [2].

Estimation of cardiovascular risk

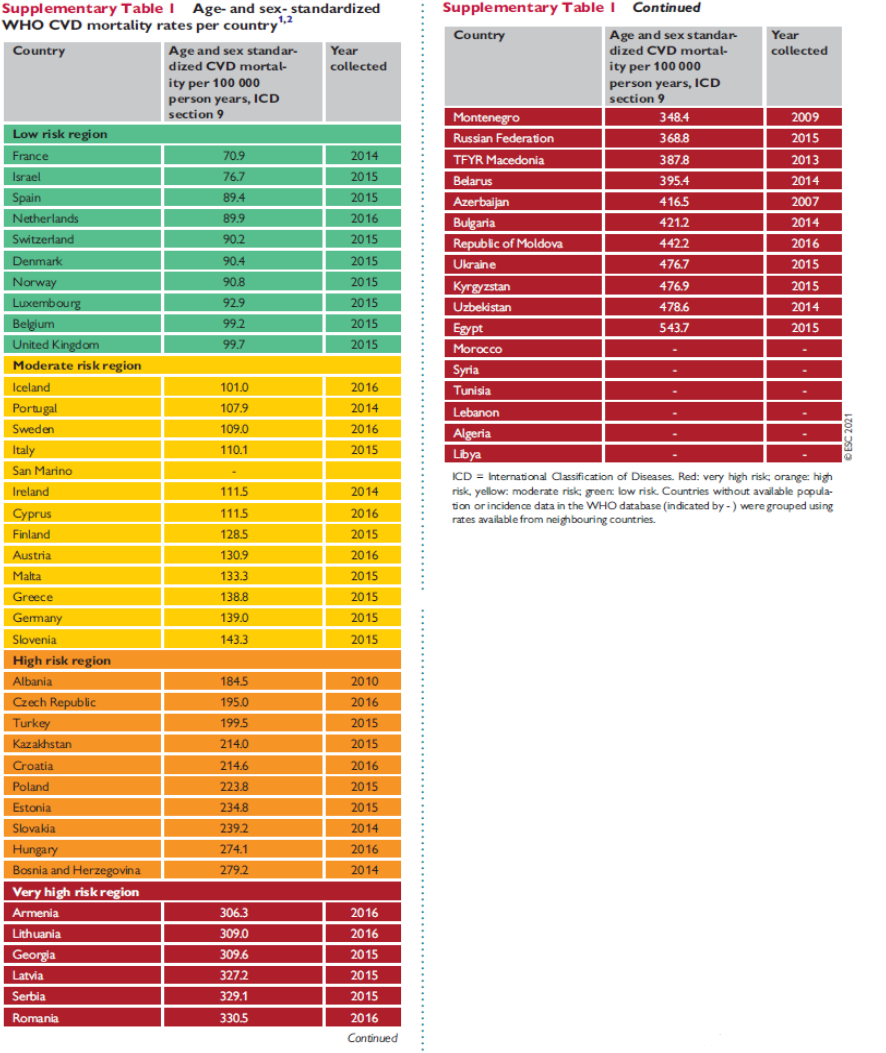

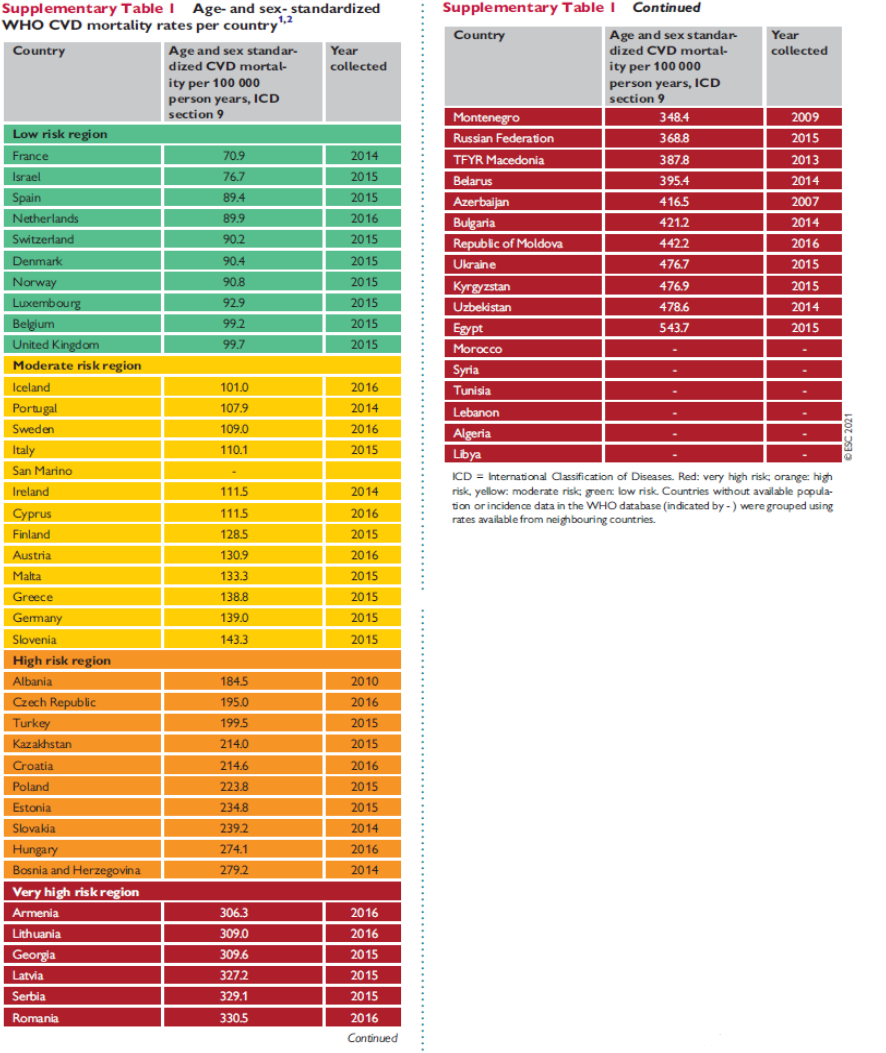

Currently CV risk is calculated using charts which combine risk factors considering the level of risk of countries: Low, moderate, high or very high risk (Table 1) [3]. The easiest way of doing it is opening www.heartscore.org at your country’s risk and entering data. Charts combine age, sex, smoking status, systolic blood pressure and non-HDL cholesterol (Total cholesterol – HDL cholesterol). Charts are accessible in 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention [3]. Risk figures achieved must be evaluated depending on age to know the personal level of CV risk: Low, moderate or high.

Table 1. Taken from 2021 ESC guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice [3]

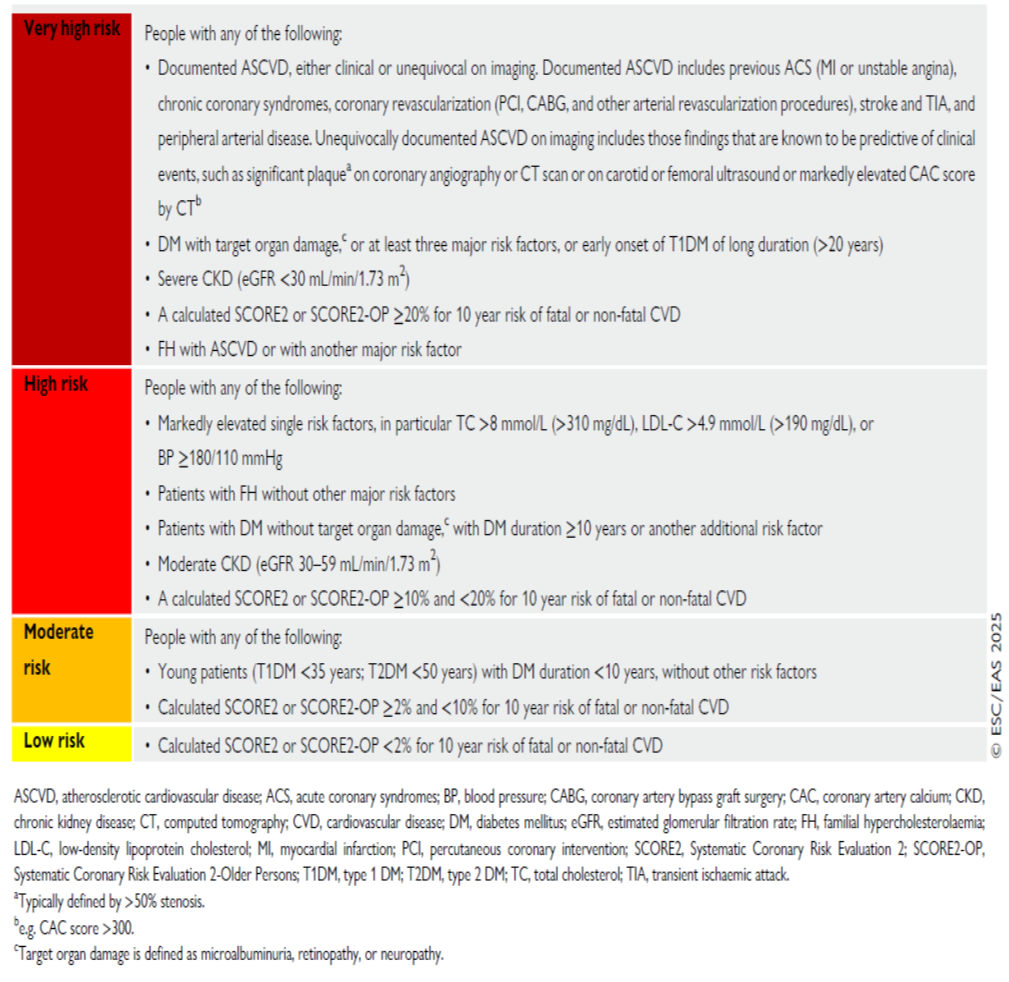

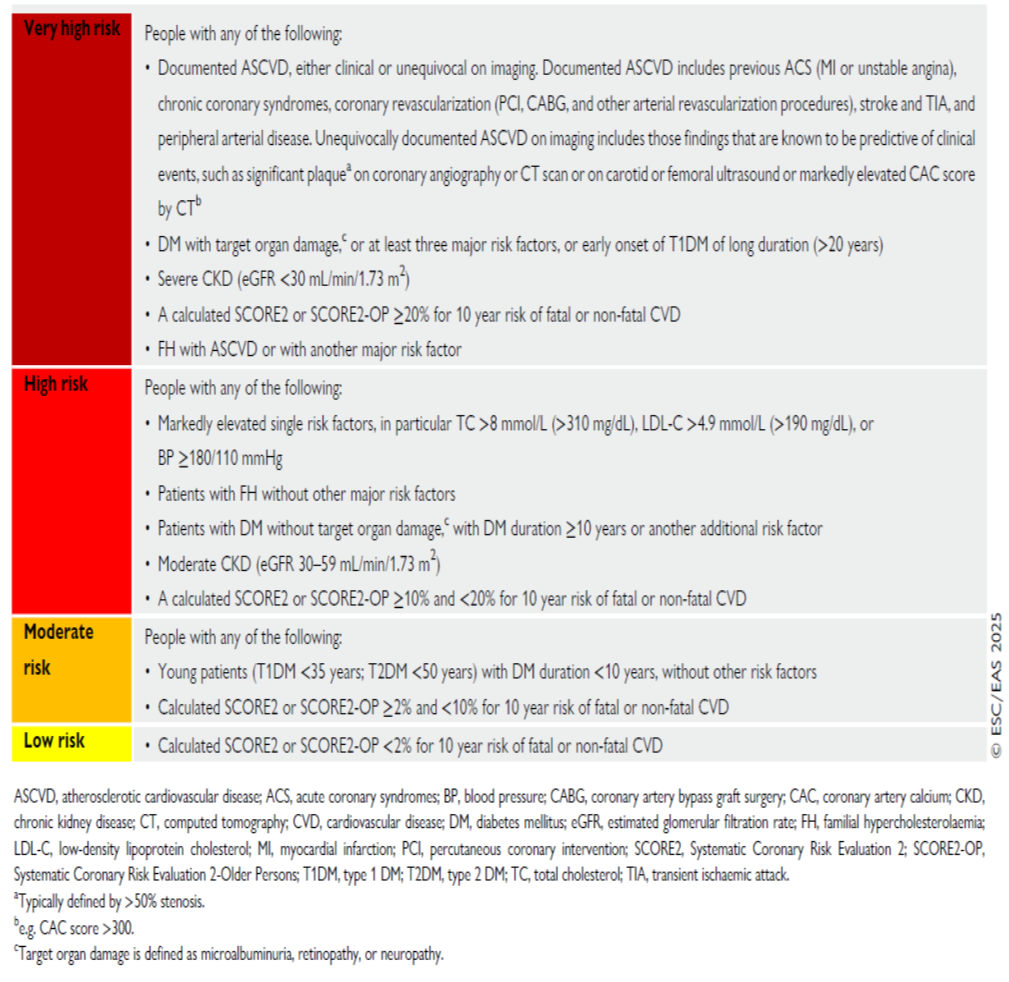

Each risk figure implies an estimation of 10-year risk of (fatal and non-fatal) CV events in that risk population. This calculation is intended for people without known CV disease. Other situations imply different levels of risk (Table 2) [2]. Diabetes mellitus (DM) in young people supposes a moderate risk, which increases to high risk when duration is ≥ 10 years or there are other risk factors and to very high risk when microangiopathy exists. An estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) between 30-59 mL/min/1.73 m2 indicates high risk level and if eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 (severe chronic kidney disease (CKD)) we have very high risk. Familial hypercholesterolemia means a high risk for total CV events, which increases to very high risk when another risk factor is added. All patients with known atherosclerotic CVD are at very high risk level.

Table 2. Taken from 2025 focused update of the 2019 ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias [2]

Each level of CV risk implies a goal for LDL-cholesterol. These goals were established by the European Society of Cardiology in 2019 [4]:

- Low risk level: LDL-Cholesterol < 116 mg/dL (Class IIb recommendation)

- Moderate risk level: LDL-Cholesterol < 100 mg/dL (Class IIa recommendation)

- High risk level: LDL-Cholesterol < 70 mg/dL (Class I recommendation)

- Very high risk level: LDL-Cholesterol < 55 mg/dL (Class I recommendation)

Treatment of hypercholesterolemia

Treatment of hypercholesterolemia begins with statins. If goals are not attained, we add ezetimibe. If goals are not attained yet, we add PCSK9 inhibitors. In case of intolerance or adverse effects with statins, we can change them for bempedoic acid.

Statins

Statins competitively inhibit the HMG-CoA reductase enzyme, which synthetizes cholesterol in the liver. Then, through LDL-cholesterol receptors, liver removes cholesterol from blood to compensate the lack of synthesis, so lowering cholesterol levels in plasma. In the Cholesterol Treatment Trialist (CTT) meta-analysis [5], 26 randomized clinical trials (RCT) were analyzed, showing a reduction of 22 % of major cardiovascular events (MACE) per 1 mmol/L of LDL-cholesterol reduction. That includes CV death and total mortality.

Rhabdomyolisis is the worst side effect of statins, but is rare (1-3 cases/100 000 patient-years [6]. Myalgia is much more frequent (10-15 %) [7], and can compel us to change or stop treatment. Pitavastatin may be an alternative, or bempedoic acid too.

Cholesterol absortion inhibitors

Ezetimibe inhibits absortion of dietary cholesterol at small bowel endothelium, by interacting with the Niemann-Pick C1-like protein 1, without affecting the absortion of fat-soluble nutrients. This decreases the offer of cholesterol to the liver, which enhances the uptake of blood cholesterol through LDL-receptors, so lowering cholesterol levels in plasma. Ezetimibe alone reduces LDL-cholesterol levels by 18 % [8], and when added to statin therapy, reduction attains around 20 % more, if we compare with the effect of statin alone [9]. The association of simvastatin plus ezetimibe has proved a reduction in MACE (IMPROVE-IT trial) [10].

Bempedoic acid

Bempedoic acid inhibits the enzyme ATP-citrate lyase, which acts before HMG-CoA reductase does, as statins do, in cholesterol synthesis. This drug decreases LDL -cholesterol by 18% [11], and combined with ezetimibe the reduction reaches 38% [12]. The CLEAR study showed a 13% reduction in MACE vs. placebo in statin intolerant patients treated with bempedoic acid. Muscle side effects of bempedoic acid were comparable to placebo [13]. This allows its use when statins are not tolerated.

Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors (PCSK9 inh)

PCSK9 controls the expression of hepatic LDL receptors. PCSK9 inhibition increases the number and action of LDL receptors, which remove cholesterol from blood, so lowering its levels. There are two drugs in the market, both monoclonal antibodies: evelocumab and alirocumab. These drugs decrease LDL-cholesterol levels by 46%-73% when combined with statins [14]. They are administered subcutaneously every two weeks, and act through LDL-receptors; that’s why they have little effect in patients with homocigous familial hypercholesterolemia (HoFH). However, they slightly lower LPa. FOURIER [15], a RCT with evelocumav, randomized patients with atherosclerotic CVD (coronary artery disease, peripheral arterial disease or stroke), and got a decrease of 15% in MACE. ODYSSEY [16], a RCT with alirocumab in patients after a recent acute coronary syndrome, got same benefit, but included an all-cause mortality reduction.

Inclisiran is an interfering RNA molecule which inhibits the synthesis of PCSK9. It’s administered subcutaneously every 6 months, and lowers LDL-cholesterol by around 50% [17]. It’s ability to decrease MACE is being studied in two phase III RCT which are currently ongoing.

There’s another research molecule, VERVE-102, which inhibits the gene related to the synthesis of PCSK9. An open-label, fase 1b, single ascending dose study (VT-10201) is currently ongoing to evaluate the safety of this drug (NCT 06164730).

Drugs for homocigous familial hypercholesterolemia

Lomitapide: Lomitapide is an inhibitor of the microsomal triglyceride transfer protein, so inhibiting the formation of VLDL in the liver and chylomicrons in the intestine. This drug is intended for HoFH patients, in combination with statins, since they don’t respond to other therapies. In a titration study lomitapide reduced LDL-cholesterol by 44% in this population [18]. There are no studies on CV outcomes with this drug.

Mipomersen: Mipomersen is an oligonucleotide which binds to the mRNA of ApoB-100, reducing the production of LDL and LPa, and is indicated in HoFH too, but is not approved by the European Medicines Agency.

Evanicumab: Evanicumab is a monoclonal antibody against angiopoietin-like 3 which has shown reductions of LDL-cholesterol around 50% in these patients [19].

Drugs to raise HDL-cholesterol

Molecules as evacetrapib or anacetrapib (cholesteryl ester transfer protein inhibitors) increase > 100% HDL levels with no or slightly decrease of LDL levels, but have no proved beneficial effects on MACE, and are not in the market.

Treatment of hypertriglyceridemia

Fibrates

These drugs are agonists of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPAR-α), lowering trygliceride (TG) levels around 50% and LDL-cholesterol < 20% [20]. Fibrates have not shown a decrease in MACE in RCT. They can be used (better fenofibrate) added to statins to reduce TG > 200 mg/dL in high risk patients with controlled LDL-cholesterol levels (IIb recommendation) [21].

OMEGA-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA)

These fatty acids seem to interact also with PPAR-α, decreasing TG levels up to 25% [22]. REDUCE-IT trial [23], evidenced a decrease in MACE in high risk patients on statins with LDL-levels < 100 mg/dL and TG levels > 150 mg/dL. PUFA used was icosapent ethyl. However, in another study (STRENGTH [24]) there was not a significant effect on MACE, perhaps because of the different PUFA employed: Combined eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). Current recommendation (IIa) is to use high dose icosapent ethyl in addition to statins in high risk patients with TG > 150 mg/dL2).

Antisense oligonucleotides

Volanesorsen: Volanesorsen is an antisense oligonucleotide targeting ApoC-III mRNA, which lowers TG by 70%, evidenced in the COMPASS study [25], which randomized patients with TG > 500 mg/dL, including patients with familial chylomicronemia syndrome (FCS). A reduction in pancreatitis has been demonstrated in a meta-analysis [26]. This drug is currently approved to treat FCS when other drugs and diet had failed, and there’s high risk of pancreatitis (IIa recommendation)2.

Olezarsen: Olezarsen is another antisense oligonucleotide which inhibits ApoC-III, reducing TG levels by 60% (Essence–TIMI 73b trial [27]), but there’s no information on MACE or reduction of pancreatitis.

Treatment of elevated Lp(a) levels

LP(a) is the covalent union of a LDL lipoprotein with a glycoprotein, apolipoprotein (a) (apo(a)) [28]. Its levels depend mainly on genetics (90%) [29]. LP(a) levels > 50 mg/dL are associated with a rise of atherosclerotic CVD and aortic valve stenosis incidences [30]. At the moment, there are no approved treatments to lower this lipoprotein. Since high levels of LP(a) implies higher CV risk, they should be considered a risk-modifying factor, underscoring the need for strong treatment of other risk factors,i.e. hypercholesterolemia. Some natural products, as l-carnitine, coenzyme Q 10, and xuezhikang, have shown the ability to decrease LP(a) levels [31]. However, there are no studies so far linking a decrease of LP(a) levels with a reduction of MACE. Muvalaplin, [32] an oral small molecule inhibitor of LP (a) hepatic synthesis, and zerlasiran [33], a small interfering RNA , have demonstrated decreases of 80%-90% of LP(a) levels in phase 2 RCT.

Conclusion

Estimation of cardiovascular risk is essential to plan prevention strategies for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Control of hyperlipidemia remains a cornerstone of risk reduction. The growing array of lipid-lowering therapies enables personalized management to achieve lipid targets and lower cardiovascular events according to individual risk.

Conflicts of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Townsend N, Nichols M, Scarborough P, Rayner M (2015) Cardiovascular disease in Europe–epidemiological update 2015. Eur Heart J 36: 2696-2705. [Crossref]

- Mach F, Koskinas KC, Roeters van Lennep JE, Tokgözoğlu L, Badimon L, et al. (2025) 2025 Focused Update of the 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias. G Ital Cardiol 26: 1-20. [Crossref]

- Visseren FL, Mach F, Smulders YM, Carballo D, Koskinas KC, et al. (2021) 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. European Heart J 42: 3227-3337. [Crossref]

- Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, Koskinas KC, Casula M, et al. (2020) 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: Lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur Heart J 41: 111-188. [Crossref]

- Baigent C, Blackwell L, Emberson J, Holland LE, Reith C, et al. (2010) Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: A meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet 376: 1670-1681. [Crossref]

- Law M, Rudnicka AR (2006) Statin safety: A systematic review. Am J Cardiol 97: C52-C60. [Crossref]

- Bruckert E, Hayem G, Dejager S, Yau C, Begaud B, et al. (2005) Mild to moderate muscular symptoms with high-dosage statin therapy in hyperlipidemic patients–the PRIMO study. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 19: 403-414. [Crossref]

- Pandor A, Ara RM, Tumur I, Wilkinson AJ, Paisley S, et al. (2009) Ezetimibe monotherapy for cholesterol lowering in 2,722 people: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Intern Med 265: 568-580. [Crossref]

- Morrone D, Weintraub WS, Toth PP, Hanson ME, Lowe RS, et al. (2012) Lipid-altering efficacy of ezetimibe plus statin and statin monotherapy and identification of factors associated with treatment response: A pooled analysis of over 21,000 subjects from 27 clinical trials. Atherosclerosis 223: 251-261. [Crossref]

- Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, McCagg A, White JA, et al. (2015) Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 372: 2387-2397. [Crossref]

- Ray KK, Bays HE, Catapano AL, Lalwani ND, Bloedon LT, et al. (2019) Safety and efficacy of bempedoic acid to reduce LDL cholesterol. N Engl J Med 380: 1022-1032. [Crossref]

- Bays HE, Baum SJ, Brinton EA, Plutzky J, Hanselman JC, et al. (2021) Effect of bempedoic acid plus ezetimibe fixed-dose combination vs ezetimibe or placebo on low- density lipoprotein cholesterol in patients with type 2 diabetes and hypercholesterolemia not treated with statins. Am J Prev Cardiol 8: 100278. [Crossref]

- Nissen SE, Lincoff AM, Brennan D, Ray KK, Mason D, et al. (2023) Bempedoic acid and cardiovascular outcomes in statin-intolerant patients. N Engl J Med 388: 1353-1364. [Crossref]

- Cho L, Rocco M, Colquhoun D, Sullivan D, Rosenson RS, et al. (2016) Clinical profile of statin intolerance in the phase 3 GAUSS-2 Study. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 30: 297-304. [Crossref]

- Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, Honarpour N, Wiviott SD, et al. (2017) Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 376: 1713-1722. [Crossref]

- Schwartz GG, Steg PG, Szarek M, Bhatt DL, Bittner VA, et al. (2018) Alirocumab and cardiovascular outcomes after acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med 379: 2097-2107. [Crossref]

- Ray KK, Wright RS, Kallend D, Koenig W, Leiter LA, et al. (2020) Two phase 3 trials of Inclisiran in patients with elevated LDL cholesterol. N Engl J Med 382: 1507-1519. [Crossref]

- Cuchel M, Meagher EA, du Toit Theron H, Blom DJ, Marais AD, et al. (2013) Efficacy and safety of a microsomal triglyceride transfer protein inhibitor in patients with homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia: A single-arm, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet 381: 40-46. [Crossref]

- Gaudet D, Greber-Platzer S, Reeskamp LF, Iannuzzo G, Rosenson RS, et al. (2024) Evinacumab in homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia: Long-term safety and efficacy. Eur Heart J 45: 2422-2434. [Crossref]

- Chapman MJ, Redfern JS, McGovern ME, Giral P (2010) Niacin and fibrates in atherogenic dyslipidemia: Pharmacotherapy to reduce cardiovascular risk. Pharmacol Ther 126: 314-345. [Crossref]

- Catapano AL, Farnier M, Foody JM, Toth PP, Tomassini JE, et al. (2014) Combination therapy in dyslipidemia: Where are we now? Atherosclerosis 237: 319-335. [Crossref]

- Ballantyne CM, Bays HE, Kastelein JJ, Stein E, Isaacsohn JL, et al. (2012) Efficacy and safety of eicosapentaenoic acid ethyl ester (AMR101) therapy in statin-treated patients with persistent high triglycerides (from the ANCHOR study). Am J Cardiol 110: 984-992. [Crossref]

- Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, Brinton EA, Jacobson TA, et al. (2019) Cardiovascular risk reduction with icosapent ethyl for hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med 380: 11-22. [Crossref]

- Nicholls SJ, Lincoff AM, Garcia M, Bash D, Ballantyne CM, et al. (2020) Effect of high- dose omega-3 fatty acids vs corn oil on major adverse cardiovascular events in patients at high cardiovascular risk: The STRENGTH randomized clinical trial. JAMA 324: 2268-2280. [Crossref]

- Gouni-Berthold I, Alexander V, Digenio A, DuFour R, Steinhagen-Thiessen E, et al. (2017) Apolipoprotein C-III inhibition with volanesorsen in patients with hypertriglyceridemia (COMPASS): A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Atherosclerosis Supp 28: e1-e2.

- Alexander VJ, Karwatowska-Prokopczuk E, Prohaska TA, Li L, Geary RS, et al. (2024) Volanesorsen to prevent acute pancreatitis in hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med 390: 476-477. [Crossref]

- Bergmark BA, Marston NA, Prohaska TA, Alexander VJ, Zimerman A, et al. (2025) Targeting APOC3 with olezarsen in moderate hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med 393: 1279-1291. [Crossref]

- Boffa MB, Koschinsky ML (2024) Lipoprotein(a) and cardiovascular disease. Biochem J 481: 1277-1296. [Crossref]

- Nordestgaard BG, Langsted A (2024) Lipoprotein(a) and cardiovascular disease. Lancet 404: 1255-1264. [Crossref]

- Patel AP, Wang M, Pirruccello JP, Ellinor PT, Ng K, et al. (2021) Lp(a) (lipoprotein[a]) concentrations and incident atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: New insights from a large national biobank. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 41: 465-474. [Crossref]

- Momtazi-Borojeni AA, Katsiki N, Pirro M, Banach M, Rasadi KA, et al. (2019) Dietary natural products as emerging lipoprotein(a)-lowering agents. J Cell Physiol 234: 12581-12594. [Crossref]

- Nicholls SJ, Ni W, Rhodes GM, Nissen SE, Navar AM, et al. (2025) Oral muvalaplin for lowering of lipoprotein(a): A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 333: 222-231. [Crossref]

- Nissen SE, Wang Q, Nicholls SJ, Navar AM, Ray KK, et al. (2024) Zerlasiran-a small-interfering RNA targeting lipoprotein(a): A phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 332: 1992-2002. [Crossref]