Sialoliths are calcified structures found within the ducts of salivary glands. They are most common in the submandibular gland and they less frequently developed in parotid gland. Sialoliths affecting the parotid glands are usually small, unilateral and are located in the Stensen's duct. These can be symptomatic or asymptomatic and these are highly radiolucent. In this report, the diagnosis and treatment of an unusual radiopaque parotid sialolith in a 53-year-old man in the right Stensen’s duct was presented.

parotid gland, stensen’s duct, sialolith, salivary gland, salivary stone

Sialoliths are the genesis of a calcified obturation in the salivary gland. They are in the idiopathic group in the classification of soft tissue calcifications [1].

It was reported that sialoliths influences 12 of every 1000 patients in the adult population [2,3]. They usually occur at 3rd and 6th decades of life and mostly seen in the middle-aged patients. Males are affected twice as much as females [4]. More than 80% of salivary stones occur in the submandibular gland or duct, 6–15%occur in the parotid gland and duct, 2% are in the sublingual and minor salivary glands [5].

The certain aetiology of sialoliths remains unknown [6]. Head and neck radiotherapy, renal impairment, some medications (anticholinergics, antisialogogues) and several systemic diseases (gout, Sjogren’s syndrome) can predispose patients to sialolith formation [7–9].

Some sailoliths are homogeneously radiopaque, some ones have a large number of calcification layers. Sialoliths of parotid gland can be highly radiolucent, because this gland secretion has a low mineral content. A single sialolith usually occur but more than one can be found in the parotid gland [9].

Sialoliths may be asymptomatic or symptomatic. The symptoms are pain and swelling, but not severe because the canal is not obstructive completely [10]. Recurrent sialoliths occur in 9% of patients. About 10% of patients with sialolith also have nephrolithiasis.

A periapical radiograph is placed within the buccal vestibule to view the sialoliths of the Stensen’s duct. The X-rays are directed to the cheek area with reduced exposure time. Sialoliths also can be seen on panoramic and anteroposterior graphs [11]. If these techniques are insufficient, CT and CBCT can be used. Sialography is used when suspicious of non-calcified stones.

The parotid sialoliths are more rarely seen than submandibular ones and are usually found in the duct [3]. They are usually small and less than 1 cm, however big stones have been reported [12].

A 53-year-old male patient was referred to our clinic with a complaint of painless swelling on the right cheek. The patient had noticed this swelling for approximately one year. The patient has type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, Parkinson’s disease and uses antiplatelet agents.

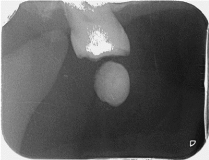

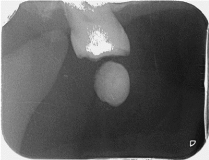

The extraoral examination did not show any symptoms. Intraoral examination revealed non-tender, mobile and firm swelling on his right cheek region (Figure 1). The mucosa was pale due to pressure of a mass. Periapical radiograph in the buccal vestibule (reducing exposure parameters) indicated a calcified mass on around the orifice of Stensen’s duct (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Intraoral view shows sialolith on Stensen’s duct entrance.

Figure 2. Periapical view in the buccal vestibule.

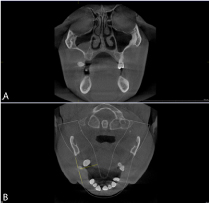

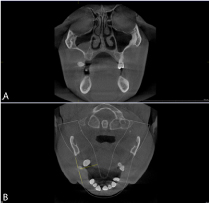

Panoramic radiograph revealed a big radiopacity on the right cheek region at the alignment of the first molar (Figure 3). The patient was admitted for CBCT images showed a radiopaque mass measured about: 11.19 × 7.19 mm in coronal section, 6.28 × 8.97 mm in cross sectional section, 8.31 × 11.50 mm in axial section (Figure 4a,4b).

Figure 3. Panoramic projection showing the stone.

Figure 4a. Coronal section on cone beam CT 4b. Axial section on cone beam CT

The lesion was diagnosed as a parotid sialolith, on the base of radiographical and clinical findings. The sialolith in this case was removed with the transoral duct incision after applying local anaesthesia (Figure 5a,5b).

Figure 5a. Postoperative image.

Sialoliths represent approximately one third of salivary gland diseases [6]. They are mostly seen in the middle-aged patients [5]. The patient's age is in our case was 53 years, this is general age range [13–15].

Salivary stones are generally represented with characteristic symptoms. These are swelling and pain of the related salivary gland, during food intake [16] Some salivary stones may be asymptomatic and determined accidentally during maxillofacial imaging. Bimanual intraoral palpation is a useful method for detecting stones. Parotid sialoliths can be palpated around the Stensen’s duct orifice or along its route [10] In our case, the patient had painless swelling on the right cheek and we could palpate the stone at the Stensen’s duct orifice.

Parotid sialoliths are smaller and more radiolucent than submandibular sialolithiasis. Conventional X-Rays may not be sufficient for imaging this stone [13].

Conventional and advanced imaging techniques are useful in the diagnosis of salivary stones [17,18]. Advanced techniques contain ultrasonography, scintigraphy, sialography, sialo endoscopy, computerized tomography, cone beam computerized tomography and magnetic resonance. Conventional techniques are panoramic, periapical and trans occlusal radiographs.

For parotid gland, periapical view in the buccal vestibule (reducing the exposure parameters) is most generally used.

Sialography is indicated when sialoliths are radiolucent. The film usually shows contrast medium present behind stone. Scintigraphy is used for patients who are contraindicated to the sialography and who do not have permeable ducts. Recently, CBCT is being used with high resolution and low dose radiation and a non-invasive method in dentomaxillofacial radiology and also diagnosis of sialoliths [17,19]. Ultrasonography is a good diagnostic technique to reveal ductal and mineralized stones with a correctness of 99% [17,18].

In the present case, periapical and panoramic radiographs were used in initial examination. CBCT images (taken for implant planning) were helpful in visualization of the structure and determining the size and location of the calcified mass. In the presence of small salivary stones, treatment should be medical rather than surgical.

The methods of treatment can be conservative or surgical. A conservative track, including oral analgesia, hydration, local heat therapy and sialagogues to promote ductal secretions are proposed [20]. The endoscopically-assisted technique for the retrieval of parotid sialoliths is a gland protector method. The success rate of this method is high and postoperative complications are low. Interventional sialendoscopy is successful for sialoliths that is mobile and less than 5 mm [21]. Open surgical treatment is conducted for sialoliths for which non-invasive treatment failed and depends on the stone size and location [22]. Open surgical procedures include transoral ductal incision, external approaches, or a combined venture [23].

In our case, open surgical treatment had to be done. In this report, we presented a parotid sialolith in a 53-year-old man with its clinical and radiological features and CBCT evaluation.

- White SC, Pharoah MJ (2008) Oral radiology principles and interpretation. Chapter 28 “Soft tissue calcification and ossification”. Mosby, Missouri. Pg 530

- Boffano P, Gallesio C (2010) Surgical treatment of a giant sialolith of the Wharton duct. J Craniofac Surg 21: 134-135. [Crossref]

- Lustmann J, Regev E, Melamed Y (1990) Sialolithiasis. A survey on 245 patients and a review of the literature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 19: 135-138. [Crossref]

- Iqbal A, Gupta AK, Natu SS, Gupta AK (2012) Unusually large sialolith of Wharton's duct. Ann Maxillofac Surg 2: 70-73. [Crossref]

- Graziani F, Vano M, Cei S, Tartaro G, Mario G (2006) Unusual asymptomatic giant sialolith of submandibular gland. A clinical report. J Craniofacial Surg 17: 549-552. [Crossref]

- Torres-Lagares D, Barranco-Piedra S, Serrera-Figallo MA, Hita-Iglesias P, Martínez-Sahuquillo-Márquez A, et al. (2006) Parotid sialolithiasis in Stensen's duct. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 11: E80-84. [Crossref]

- Ship JA (2002) Diagnosing, managing, and preventing salivary gland disorders. Oral Dis 8: 77-89. [Crossref]

- Eigner TL, Jastak JT, Bennett WM (1986) Achieving oral health in patients with renal failure and renal transplants. J Am Dent Assoc 113: 612-616. [Crossref]

- Sharma RK, al-Khalifa S, Paulose KO, Ahmed N (1994) Parotid duct stone--removal by a dormia basket. J Laryngol Otol 108: 699-701. [Crossref]

- Williams MF (1999) Sialolithiasis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 32: 819-834. [Crossref]

- Gadodia A, Bhalla AS, Sharma R, Thakar A, Parshad R (2011) Bilateral parotid swelling: a radiological review. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 40: 403-414. [Crossref]

- Siddiqui SJ (2002) Sialolithiasis: an unusually large submandibular salivary stone. Br Dent J 193: 89-91. [Crossref]

- Bodner L (1999) Parotid sialolithiasis. J Laryngol Otol 113: 266-267. [Crossref]

- Konstantinidis I, Paschaloudi S, Triaridis S, Fyrmpas G, Sechlidis S, et al. (2007) Bilateral multiple sialolithiasis of the parotid gland in a patientwith Sjögren’s syndrome. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 27:41-44. [Crossref]

- Leung AK, Choi MC, Wagner GA (1999) Multiple sialoliths and a sialolith of unusual size in the submandibular duct: a case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 87: 331-333. [Crossref]

- Pollack CV Jr, Severance HW Jr (1990) Sialolithiasis: case studies and review. J Emerg Med 8: 561-565. [Crossref]

- Oteri G1, Procopio RM, Cicciù M (2011) Giant Salivary Gland Calculi (GSGC): Report of Two Cases. Open Dent J 5: 90-5. [Crossref]

- Yoshimura Y, Inoue Y, Odagawa T (1989) Sonographic examination of sialolithiasis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 47: 907-912. [Crossref]

- Capaccio P, Torretta S, Ottavian F, Sambataro G, Pignataro L (2007) Modern management of obstructive salivary diseases. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 27: 161-172. [Crossref]

- Moghe S, Pillai A, Thomas S, Nair PP (2012) Parotid sialolithiasis. BMJ Case Rep 2012. [Crossref]

- Capaccio P, Gaffuri M, Pignataro L (2014) Sialendoscopy-assisted transfacial surgical removal of parotid stones. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 42: 1964-1969. [Crossref]

- Daniel SJ, Kanaan A (2015) Open surgical management of sialolithiasis. Oper Tech Otolayngol Head Neck Surg 26: 143–149.

- Samani M, Hills AJ, Holden AM, Man CB, McGurk M (2016) Minimally-invasive surgery in the management of symptomatic parotid stones. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 54: 438-442. [Crossref]