Abstract

We studied if and how the association between grandiose narcissistic traits and juvenile delinquency is mediated by self-esteem and shame regulation strategies. An ethnic diverse and mixed gender sample of 59 delinquent and 275 non-delinquent adolescents between 13 and 18 years of age participated in a survey study, using the Childhood Narcissism Scale (CNS), the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) and the Compass of Shame Scale (CoSS). Narcissism showed a weak positive correlation with self-esteem and externalizing shame regulation. Self-esteem correlated strongly and negatively with internalizing shame regulation and Shame Proneness. Logistic regression analysis showed high SES to be negatively associated with delinquency. Also, self-esteem moderated the relation between narcissism and delinquency in that high self-esteem did increase the chance of narcissism leading to delinquency.

Introduction

Research has identified criminal history and aggression as the most important risk factors for (persistent) delinquent behavior among juveniles [1,2]. These risk factors have been studied far more often than personality characteristics, such as narcissism, self-esteem, and shame regulation, although self-esteem has gained some attention in research on strength-based approaches to offender rehabilitation [3]. In our research, we focus on the interplay between these three personality characteristics and aggression in the explanation of delinquency.

Clinically, narcissism is conceptualized as a personality trait the subject is not aware of. Therefore, narcissistic traits stealthily invade daily life. Subjects with strong grandiose narcissistic traits tend to have a hostile perspective of the world, to expect to be a target of transgressions by others, and to activate aggressive emotional reaction patterns [4]. They are more likely to be unprovoked aggressors than their low narcissistic counterparts. In a longitudinal study, Reijntjes et al. [5] showed that highly narcissistic boys were more likely than their peers to show more direct bullying, and in particular elevated indirect bullying. Clinically, one would expect such relations, because narcissists may feel entitled to show their dominance, and are prone to aggression by the working of the shame-rage spiral [6]. The relations between narcissism and aggression seem above all to pertain to adolescents who score high on self-esteem.

Self-esteem differs clinically from narcissism: ‘When we deal with self-esteem, we are asking whether the individual considers himself adequate – a person of worth – not whether he considers himself superior to others’ [7]. The relation between self-esteem and aggression is equivocal. Some authors assume that aggression results from being provoked to strike out, sometimes even preemptory, as a means to counter a potential threat to self-esteem in subjects who have low self-esteem [8-10]. The anger, evoked by the threat, is externalized by attacking the person who is perceived as representing this threat. Anger can even be evoked without the presence of a ‘real’ threat: for aggression to occur, internally felt or fantasized threats to self-esteem suffice as well. Recently, the focus has shifted, and aggression is now thought to be associated with high self-esteem: subjects who have high self-esteem are relatively prone to perceive a threat [11,12].

Research showed that grandiose narcissism and self-esteem are only weakly to moderately correlated [13]. Brummelman et al., [13] summarize the differences between narcissism and self-esteem as follows: “Narcissism is nurtured by parental overvaluation, (….) and self-esteem is nurtured by parental warmth. Clinically, narcissists think of themselves as superior to others (reflecting a vertical, hierarchical view of themselves in relation to others), whereas those high in self-esteem think of themselves as worthy (reflecting a horizontal, nonhierarchical view of themselves in relation to others). Narcissism peaks in adolescence and then gradually decreases throughout adulthood [14]. By contrast, self-esteem is lowest in adolescence and then gradually increases throughout adulthood [15].”

Research on the relation between narcissism, self-esteem and aggression showed a robust relation between low self-esteem and aggression, yet the effect of low self-esteem on aggression was found to be independent of narcissism [16]. On the other hand, it was also found that narcissistic subjects are aggressive only following threats to self-esteem [9,11]. Clinically, the relation between threats to narcissistic grandiose traits and self-esteem on the one hand, and the resulting aggression or delinquency on the other hand, is expected to be mediated by shame [17-19]. Feeling shame over being a person who is being aggressive or commits criminal acts, should prevent from doing so. Shame is a powerful self-conscious emotion which touches on self-esteem [20]. Grandiose narcissism, with an inflated sense of self-worth is characterized by a relative lack of shame, whereas high positive self-esteem is associated with moderate shame levels.

People differ in their proneness to experience shame and in the way they cope with shame, using various internalizing and externalizing strategies [21]. Some may react in an internalizing way to self-esteem blows by devaluing themselves, resulting in a shame–rage spiral [6]. Others, however, react in an externalizing way to shame by turning the evoked anger outside. Clinically, following DSM-5 [22], grandiose narcissistic traits are associated with a relative lack of shame, whereas vulnerable narcissistic traits are associated with shame proneness [23,24].

Several studies found relations between shame, aggression, and delinquency [25-28]. In a meta-analysis of self-conscious emotions and offending, higher levels of proneness to experience shame and guilt were associated with less delinquency [29]. Guilt proved to be stronger associated with less delinquency than shame, with a medium and small effect size, respectively. Notably, there was a trend showing that shame was unrelated to delinquency, with the effect of guilt partialled out.

Research into adolescent aggression in relation to narcissism, self-esteem, and shame regulation is scarce. In Barry, Grafeman, Adler and Pickard’s study [30], narcissism and self-esteem were positively interrelated; however, only narcissism was significantly correlated with self-reported delinquency [31]. Adaptive narcissism was positively associated with self-esteem, but maladaptive narcissism was not related to self-esteem. Thomaes et al. [32] showed that grandiose narcissistic young adolescents were indeed more aggressive than others, whereas low and easily threatened self-esteem was not associated with aggression. In fact, narcissism and high self-esteem were associated with more aggression. Shame-proneness was weakly related to anger and aggression, implicating that with higher shame proneness, more aggression could be expected [33,34]. Girls who reported a high rate of shaming experiences were more likely to have shown physical aggression than girls who reported fewer shaming experiences [35,36]. Anticipating being shamed by significant others or peers may function as an informal sanction that may inhibit offending by juveniles [37]. The inhibiting effect of this anticipated shaming is that it offers self-control.

In conclusion, research with adolescents on the association between threats to narcissistic grandiosity, and the mediating function of self-esteem and shame regulation for an aggressive reaction to result is scarce to absent. To our knowledge, the present study is the first study examining the relation between narcissism, self-esteem, shame-proneness, shame regulation styles and juvenile delinquency.

The present study

The first set of three hypotheses concerned the relations between the concepts of grandiose narcissism, self-esteem and shame. Following Thomaes and Brummelman [38], we expected grandiose narcissism to be only weakly to moderately associated with high self-esteem. The second hypothesis was that high narcissism would be positively correlated with externalizing shame regulation, and negatively correlated with internalizing and adaptive shame regulation and shame proneness. The third hypothesis was that high self-esteem would be positively associated with adaptive and internalizing shame regulation, and negatively associated with shame proneness and externalizing shame regulation.

Two other hypotheses concern the moderating effect of self-esteem and shame regulation between narcissism and delinquency. We assumed that grandiose narcissism is a personality trait that is stable across many situations, and that real or imagined blows to narcissistic grandiosity will evoke shame, which can result in aggression, and subsequently can be expressed in delinquent acts. Self-esteem, shame proneness and shame regulation styles were expected to moderate the evoked aggression before delinquency to appear. Given Thomaes and Brummelman’s conclusion that narcissism and high self-esteem differ fundamentally, the fourth hypothesis was that high self-esteem would mitigate the effect of high narcissism on delinquency. The fifth hypothesis was that internalizing shame regulation strategies would reduce delinquency, whereas externalization would enhance delinquency.

In the analyses, gender, age and SES will be taken into account as possible interaction variables. Ethnicity has been shown to be associated with differences in offense patterns, in prevalence of risk factors for delinquency, and in the impact of these risk factors on recidivism [29]. Also, we have to account for the possibility that adolescents from different ethnic groups might culturally differ in proneness to experience self-conscious emotion [39]. In this study, ethnicity will be included as an interaction variable accounting for ethnic group differences that may moderate associations.

Method

Participants and procedures

A total of 334 adolescents between 13 and 18 years of age from Amsterdam and two rural cities participated. The comparison group consisted of 275 adolescents (60% male, 40% female, M = 14.5 years old, 70% were born from originally Dutch parents, 30% were having an ethnic minority background[1]). The delinquent group consisted of 59 adolescents (80% male, 20% female, M = 15.5 years old, 40% were born from originally Dutch parents, and 60% had an ethnic minority background). The comparisons were found by asking schools to participate in the project, whereas the juvenile delinquents were asked to participate by forensic psychologists examining juveniles before trial in juvenile detention centers (waiting for trial or being sentenced). All adolescents participated on a voluntary base, and informed consent was obtained from both parents and their children. The research was introduced to the participants as “a survey on the opinions of adolescents to help teachers better understand adolescents.” Absolute anonymity ensured that no outcomes could be become available to the schools or the forensic psychologists, and the results for the juvenile delinquents could not be used in the forensic psychologist’s reports.

Questionnaires

Childhood Narcissism Scale (CNS): The CNS [40] is a 10-item scale assessing grandiose views of self, inflated feelings of superiority and entitlement, and exploitative interpersonal attitudes in children and young adolescents. Items are rated along a 4-point scale. The CNS showed a Cronbach’s alpha of .84, test-retest reliability of 0.87 and good convergent validity. CNS-measured childhood narcissism and self-esteem (as measured among others with the RSES) were largely independent constructs. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was .83.

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES): The RSES [7] is a 10-item scale assessing global self-worth. Internal consistency reliability for the RSES was .88 and factor analysis suggest a single general factor [41]. Men reported slightly higher self-esteem than women. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was .85.

Compass of Shame Scale (CoSS): The CoSS [39,42] assesses individual differences in emotion-focused regulation of shame. It consists of four stems, each containing ten items. These forty 5-point Likert items, ranging from “Never” to “Almost always”, are divided into six scales. Four of these scales represent the poles of Nathanson’s [43] compass of shame theory: (a) “Attack Self” represents inward-directed anger and self-blame, (b) “Withdrawal” is the tendency to hide or withdraw when shamed, (c) “Avoidance” represents disavowal and emotional distancing or minimization of the situation in something neutral or positive, and (d) “Attack Other” represents outward-directed anger (i.e., aggression) and blaming others. “Adaptive” assesses adaptive responses to shame, with a minimum of distortion of the shame emotion: it captures the acknowledgement of shame and motivation to apologize and/or make amends. “Shame” asks after shame-proneness. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha varied between .75 and .87.

Schalkwijk et al.´s [39] analysis of the CoSS showed that the two internalizing scales (Attack Self and Withdrawal) can be aggregated into one internalizing scale. In this scale the negative emotion is acknowledged and the self is experienced as failing. The two externalizing scales (Avoidance and Attack Other) can be aggregated into one externalizing scale. In this scale experiencing negative emotions is minimized, diminishing the experience of shame.

Statistical analyses

First, missing values (less than 5%) were estimated by means of expectation maximization [44] Correlations were computed between gender, age, SES, cultural background, and educational level between juvenile offenders and comparisons. We grouped correlations as following: weak (.00 - .30), moderate (.31 - .50), strong (.51 - .80), and very strong (.81 – 1.00).

The first group of hypotheses, concerning the relation between narcissism, self-esteem and shame-regulation were tested by using univariate correlation analyses. The second group of hypotheses, concerning the relation between narcissism (independent variable), delinquency (dependent variable) and the possible moderating effects of self-esteem and shame measures, age, gender, SES, and culture were tested using logistic regression analysis.

Results

Univariate correlation analyses

The first set of three hypotheses concerned the relation between the measures of narcissism, self-esteem, and shame regulation, and were tested by means of simple correlation analyses. The first hypothesis, that narcissism and high self-esteem would be only weakly to moderately correlated, was confirmed (Table 1). The second hypothesis was that high narcissism would be positively correlated with externalizing shame regulation, and negatively correlated with internalizing and adaptive shame regulation and shame proneness. It can be derived from the correlations in Table 1 that, as expected, narcissism correlated positively with externalizing, be it weakly, whereas the correlation with shame proneness and internalizing was weakly negative. Adaptive shame regulation was not significantly correlated with narcissism. Narcissism was weakly and positively associated with delinquency, indicating that delinquents showed somewhat higher levels of narcissism. The third hypothesis was that high self-esteem would be positively associated with internalizing and adaptive shame regulation, and negatively associated with shame proneness and externalizing shame regulation. There was a weak positive correlation with adaptive shame regulation, a strong negative correlation with shame proneness and a weakly negative correlation with externalizing. Internalizing, however, was strongly and negatively associated with high self-esteem.

Table 1. Correlations between, Narcissism, Self-Esteem, and Shame Regulation

|

Narc. |

Self-Est |

Adapt. |

Shame-P |

Intern. |

Extern. |

Delinq. |

Narc. |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Self-Est. |

.298*** |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

Adaptive |

.017 |

.133** |

1 |

|

|

|

|

Shame-P. |

-.197*** |

-.559*** |

.116* |

1 |

|

|

|

Internal. |

-.156** |

-.608*** |

-.019 |

.778*** |

1 |

|

|

External. |

.288*** |

-.145** |

-.024 |

.141** |

.289*** |

|

|

Delinquency |

.155** |

.183*** |

-.012 |

-.136** |

-.164** |

.043 |

1 |

N = 334; * : p < .05, **: p < .01, ***: p < .001

Logistic regression analysis

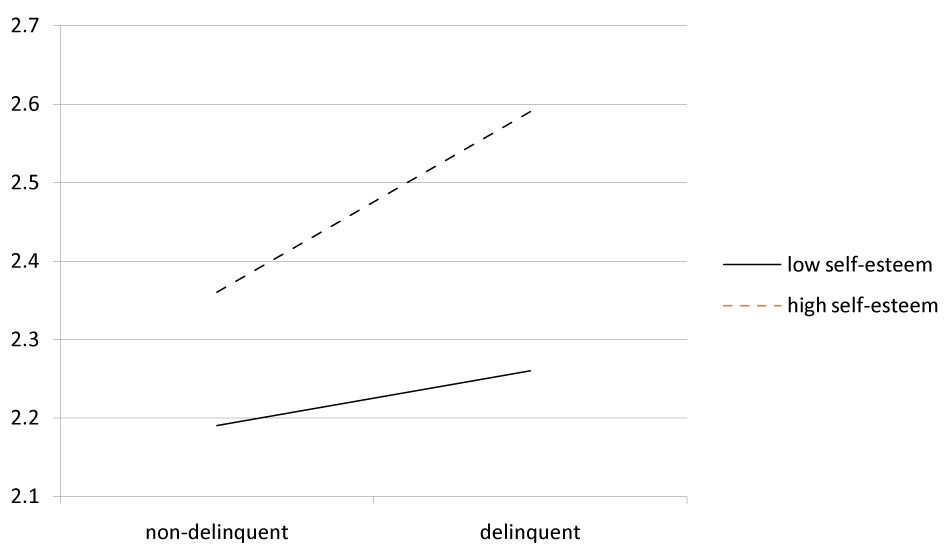

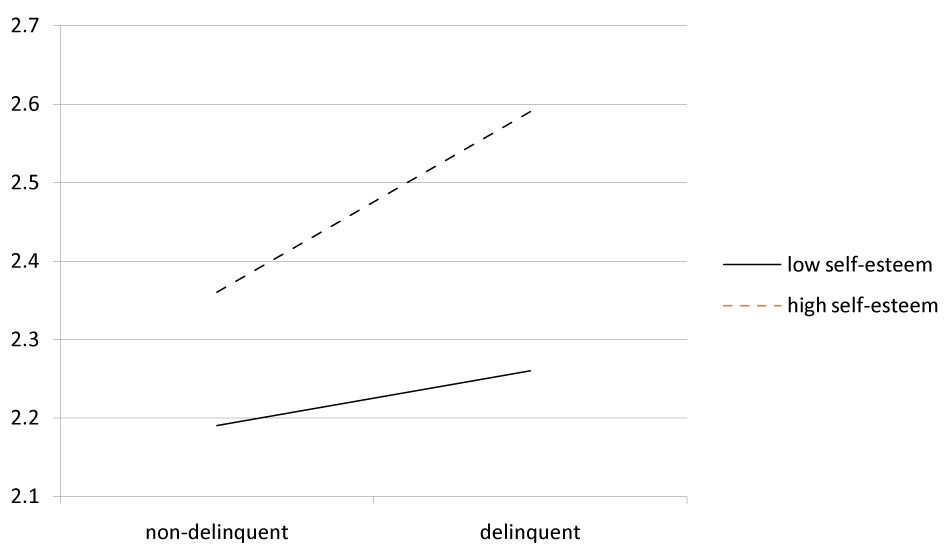

The second set of hypotheses was considered as the full theoretical model explaining delinquency, and was tested by means of a single logistic regression analysis, with all hypothesized main effects and interactions included, yielding a significant overall regression equation (Χ2 (N = 334; df = 17) = 112.068, p < .001), explaining 47% of the variance, correctly classifying 88% of the participants as delinquent or non-delinquent. The hypotheses concerned the moderating effects of self-esteem and shame in the relation between narcissism (independent variable), and delinquency (dependent variable). We only found one main effect (high SES showing a negative association with delinquency) and one significant interaction between high self-esteem and narcissism (Table 2). However, high self-esteem did not reduce the effect of high narcissism on delinquency. The reverse turned out to be the case in that high self-esteem did increase the chance of narcissism leading to delinquency. Scoring low on self-esteem did not differentiate delinquents and non-delinquents on narcissism scores, whereas scoring high on self-esteem did (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Interaction between self-esteem and narcissism

Note 1: The y-axis represents narcissism scores

Note 2: There are no significant differences between non-delinquents and delinquents on narcissism in adolescents with low self-esteem (t = 0.549, p = .584), but significant differences in adolescents with high self-esteem (t = 2.350, p = .020).

Table 2. Logistic regression analysis for the relation between narcissism, self-esteem, shame regulation and juvenile delinquency

|

B |

S.E. |

Wald. |

Df |

Sig. |

Exp(B) |

Age |

0,890 |

0,178 |

25,059 |

1 |

.000 |

2.436*** |

Gender |

-0,894 |

0,467 |

3,672 |

1 |

.055 |

0,409 |

Culture |

0,498 |

0,419 |

1.411 |

1 |

.235 |

1,645 |

SES |

-1,365 |

0,279 |

23,933 |

1 |

.000 |

0,255*** |

Narcissism |

-0,671 |

0,891 |

0,567 |

1 |

.451 |

0,511 |

Self-Est. |

0,193 |

0,503 |

0,148 |

1 |

.701 |

1,213 |

Internal. |

-0,666 |

0,414 |

2,580 |

1 |

.108 |

0,514 |

External. |

0,503 |

0,413 |

1,482 |

1 |

.223 |

1,653 |

Adaptive |

-0,067 |

0,290 |

0,053 |

1 |

.818 |

0,935 |

Shame Pr. |

0,230 |

0,440 |

0,273 |

1 |

.601 |

1,258 |

Nar.-Self-E. |

1,176 |

0,485 |

5,871 |

1 |

.015 |

3,242* |

Narc.-ShPr. |

0,078 |

0,548 |

0,020 |

1 |

.886 |

1,082 |

Narc.-Adap |

-0,026 |

0,403 |

0,004 |

1 |

.949 |

0,975 |

Narc.-Int |

0,409 |

0,580 |

0,496 |

1 |

.481 |

1,505 |

Narc-Ext |

-0,186 |

0,428 |

0,190 |

1 |

.663 |

0,830 |

Narc-Gend. |

-0,140 |

0,499 |

0.097 |

1 |

.755 |

0,869 |

Narc.-Cult |

-0.584 |

0,411 |

2.022 |

1 |

.156 |

0,558 |

Constant |

-14.858 |

4.053 |

13.436 |

1 |

.000 |

0,000*** |

N = 334; * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001

Discussion

To our knowledge, the present study is the first examining the relation between narcissism, self-esteem, shame regulation strategies and juvenile delinquency. As expected, grandiose narcissism did not show a one-to-one relation with self-esteem, as Thomaes et al. [10] proposed: narcissists think of themselves as superior to others, whereas those high in self-esteem think of themselves as worthy. Consequently, we found that adolescents scoring high on narcissism regulate their shame, if any, more by externalizing than by internalizing regulation strategies, and hardly by adaptive regulation. In contrast to narcissism, high self-esteem is associated with little shame experiences (low scores on Shame-proneness) and consequently with little need for the use of shame regulation strategies. Adolescents with high self-esteem are probably more prone to experiencing pride, the opposite of shame. If any shame coping strategies are used, they are bound to be adaptive, preserving positive self-esteem. This finding fits well with the clinical notion of many authors that the subject with strong narcissistic traits is unconsciously defending against threatening experiences of high self-esteem [45,46]. Our study replicates Barry et al.’s [30] finding that grandiose narcissism and high self-esteem partially overlap, but that they also can be differentiated on the basis of adaptive and maladaptive narcissism. In our study they are weakly correlated, but they can indeed be differentiated on the basis of the correlations with using or not using adaptive shame coping strategies.

Contrary to what we expected, the externalizing quality of shame regulation could not be associated with delinquency as an aggressive act, e.g., in the context of narcissistic rage or the shame-rage spiral. In the correlation analyses, we found that delinquency was positively and weakly associated with both narcissism and self-esteem, and weakly and negatively associated with internalizing shame strategies and shame proneness. The combination of high self-esteem and high-narcissism did even slightly increase the risk for delinquency. Referring to the ongoing discussion on whether aggression is evoked by threats to high or low self-esteem, this finding seems again to support the first option, as aggression with high narcissistic traits was also associated with threats to a positive self-image.

High Social Economic Status was found to be the sole main effect explaining delinquency, which is in line with the literature on risk and protective factors in delinquency [47].

This study has some limitations. A weakness of our study is the combination of our measures: The CNS assesses grandiose narcissism only, the RSES global self-worth, whereas the CoSS is a measure of neurotic, internalizing shame regulation. So the CoSS might not be a good measure to describe shame coping for subjects with grandiose narcissistic traits. Another drawback of our research is that the number of subjects in the study did not permit us to differentiate between the kinds of aggression in the offenses, such as reactive aggression against others following a (perceived) threat or instrumental (physical) aggression for obtaining what they want. Although we regard delinquency to be an aggressive act in se, this differentiation is especially important in theorizing about the relation between threats to narcissism and self-esteem.

These shortcomings ask for further research in which the differentiation between types of aggression is possible. The biggest challenge, however, is that the theory of narcissism is rapidly changing and challenges existing views. Until recently, clinically differentiation between grandiose (over) and vulnerable (covert) narcissism was widely accepted, and most of the experimental research on narcissism focused on grandiose narcissism [48]. In research and clinical practice these two categories were thought to be binary: the client was rated on either grandiose or vulnerable narcissism (or none at all). In the last decade, however, a hierarchical definition of pathological narcissism was proposed: it is most and for all about dysfunctional self-regulation, dysfunctional affect regulation and interpersonal difficulties [46,49]. These dysfunctions can be seen in extreme grandiosity or extreme vulnerability, which each can be expressed in a covert or overt form. If this hierarchical definition of narcissism becomes the clinical diagnostic standard, research on moderating factors between narcissism and delinquency will be changed accordingly, focusing more on fluctuations in self-esteem, adding measures for affect regulation and interpersonal difficulties (e.g., dismissive attachment). Measures for covert narcissism are still lacking.

Clinically, our research shows that differences in personality traits are not all-or-one phenomena: adolescents high on narcissism differ from adolescents high on self-esteem, but to a certain extent these are relative differences. For example, both groups do not use internalizing shame regulation strategies, but for those scoring high on self-esteem, this association is much higher than for those scoring high on grandiose narcissism. When considering treatment implications, it is important to notice that narcissism peaks in adolescence and then gradually decreases throughout adulthood, whereas self-esteem is lowest in adolescence and then gradually increases throughout adulthood [13]. The same goes for offending: moral disengagement in convicted juveniles tends to decline over time, and with it, offending [50]. Given the new line of theorizing on narcissism sketched above, treatment should focus on self-esteem fluctuations, emotion regulation capacities and aspects of interpersonal difficulties, such as a lack of empathy.

[1] Notably, in the Netherlands, an adolescent is considered to belong to an ethnic minority group when at least one of his or her parents was born outside the Netherlands.

References

- Assink M, Van Der Put CE, Hoeve M, De Vries SLA, Stams GJJM, Oort FJ (2015) Risk factors for persistent delinquent behavior among juveniles: A meta- analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review 47: 61.

- Van der Put CE, Stams GJJM, Dekovic M, Hoeve M, Van der Laan PH (2013) Ethnic differences in the prevalence and impact of risk factors for recidivism. International Criminal Justice Review 23: 113-131.

- Ward T, Mann RE, Gannon TA (2007) The good lives model of offender rehabilitation: Clinical implications. Aggression and Violent Behavior 12: 87-107.

- Reidy DE, Foster JD, Zeichner A (2010) Narcissism and unprovoked aggression. Aggress Behav 36: 414-422. [Crossref]

- Reijntjes A, Vermande M, Thomaes S, Goossens F, Olthof T, Aleva L, Van der Meulen M (2016) Narcissism, bullying, and social dominance in youth: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 44: 63-74.

- Scheff TJ, Retzinger S (1991) Emotions and Violence: Shame and Rage in Destructive Conflicts. Lexington, KY: Lexington Books.

2021 Copyright OAT. All rights reserv

- Rosenberg M (1965) Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton: Princeton University Press

- Anderson CA, Bushman BJ (2002) Human aggression. Annual Review of Psychology 53: 27-51.

- Bond AJ, Ruaro, Wingrove J (2006) Reducing anger induced by ego threat: Use of vulnerability expression and influence of trait characteristics. Personality and Individual Differences 40: 1087-1097.

- Bushman BJ, Baumeister RF, Thomaes S, Ryu E, Begeer S, et al. (2009) Looking again, and harder, for a link between low self-esteem and aggression. J Pers 77: 427-446. [Crossref]

- Baumeister RF, Bushman BJ, Campbell WK (2000) Self-Esteem, narcissism and aggression: Does violence result from low self-esteem or from threatened egotism? Current Directions in Psychological Science 1: 19-41.

- Baumeister RF, Smart L, Boden JM (1996) Relation of threatened egotism to violence and aggression: the dark side of high self-esteem. Psychol Rev 103: 5-33. [Crossref]

- Brummelman E, Thomaes S, Sedikides C (2016) Separating narcissism from self-esteem. Current Directions in Psychological Science 25: 8-13.

- Foster JD, Campbell WK, Twenge JM (2003) Individual differences in narcissism: Inflated self-views across the lifespan and around the world. Current Directions in Psychological Science 17: 469-486.

- Robins RW, Trzesniewksi KH, Tracy JL, Gosling SD, Potter J (2002) Global self- esteem across the lifespan. Psychology and Aging 17: 423-434.

- Donnellan MB, Trzesniewski KH, Robins RW, Moffitt TE, Caspi A (2005) Low self-esteem is related to aggression, antisocial behavior, and delinquency. Psychol Sci 16: 328-335. [Crossref]

- Brown RP, Zeigler-Hill V (2004) Narcissism and the non-equivalent of self-esteem measures: A matter of dominance. Journal of Research in Personality 38: 585-592.

- Egan V, Lewis M (2011) Neuroticism and agreeableness differentiate emotional and narcissistic expression of aggression. Personality and Individual Differences 50: 845-850.

- Leary MR, Terry ML, Allen AB, Tate EB (2009) The concept of ego-threat in Social and personality psychology: Is ego threat a viable scientific construct? Personality and Social Psychology Review 13: 151-164.

- Schalkwijk F (2015) The conscience and self-conscious emotions in adolescence: An integrative approach. Hove, UK: Routledge.

- Elison F, Lennon R, Pulos S (2006) Investigating the compass of shame: The development of the compass of shame scale. Social Behavior and Personality 34: 221-238.

- American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. (5thedn). Arlington, VA: APA.

- Lansky MR (2005) Hidden shame. J Am Psychoanal Assoc 53: 865-890. [Crossref]

- Ritter K, Vater A, Ruesch N, Schroeder-Abé M, Schuetz A, et al. (2014) Shame in patients with narcissistic personality disorder. Psychiatry Research 215: 429-437.

- Stuewig J, Tangney JP, Heigel C, Harty L, McKloskey L (2010) Shaming, blaming, and maiming: Functional links among the moral emotions, externalization of blame, and aggression. J Res Pers 44: 91-102. [Crossref]

- Tangney JP, Stuewig J, Hafez L (2011) Shame, guilt and remorse: Implications for offender populations. J Forens Psychiatry Psychol 22: 706-723. [Crossref]

- Tangney JP, Stuewig J, Mashek DJ, Hasting M (2011) Assessing jail inmates’ proneness to shame and guilt: Feeling bad about the behavior or the self? Crim Justice Behav 38: 710-734. [Crossref]

- Zeigler-Hill V, Clark CB, Pickard JD (2008) Narcissistic subtypes and contingent self-esteem: Do all narcissists base their self-esteem on the same domains? J Pers 76: 753-774. [Crossref]

- Spruit A, Schalkwijk F, Van Vugt E, Stams GJ (2016) A meta-analysis of self- conscious emotions and offending. Aggression and Violent Behavior 28: 12-20.

- Barry CT, Grafeman SJ, Adler KK, Pickard JD (2007) The Relations among narcissism, self-esteem, and delinquency in a sample of at-risk adolescents. J Adolesc 30: 933-942. [Crossref]

- Barry CT, Kauten RL (2014) Nonpathological and pathological narcissism; Which self- reported characteristics are most problematic in adolescents? J Pers Assess 96: 212-219. [Crossref]

- Thomaes S, Bushman BJ, Stegge H, Olthof J (2008) Trumping shame by blasts of noise: Narcissism, self-esteem, shame and aggression in young adolescents. Child Development 79: 1792-1801.

- Nystrom MBT, Mikkelsen F (2013) Psychopathy-related personality traits and shame management strategies in adolescents. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 28: 519-537.

- Robinson R, Roberts WL, Strayer J, Koopman R (2007) Empathy and emotional responsiveness in delinquent and non-delinquent adolescents. Social Development 16: 555-579.

- Aslund C, Starrin B, Leppert J, Nikkelsen KW (2009) Social status and shaming experiences related to adolescents overt aggression at school. Aggress Behav 35: 1-13. [Crossref]

- Schalkwijk F, Stams GJ, Stegge H, Dekker J, Peen J (2016) The conscience as a regulatory function: Empathy, shame, guilt, pride and moral orientation in delinquent adolescents. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol 60: 675-693. [Crossref]

- Rebellon CJ, Piquero NL, Piquero AR, Tibbetts SG (2010) Anticipated shaming and criminal offending. Journal of Criminal Justice 38: 988-997.

- Thomaes S, Brummelman E (2016) Narcissism. In: Cichetti D (ed.) Developmental Psychopathology (3rd. edn) 4: 679-725. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley

- Schalkwijk F, Ellison J, Dekker J, Peen J, Stams GJ (2016, in press) Measuring shame coping: The validation of the Compass of Shame Scale. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality 189-206.

- Thomaes S, Stegge H, Bushman BJ, Olthof T, Denissen J (2008) Development and validation of the Childhood Narcissism Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment 90: 382–391.

- Robins RW, Hendin HM, Trzesniewksi KH (2001) Measuring global self-esteem: construct validation of a single-item measure and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 27: 151-161.

- Elison F, Pulos S, Lennon R (2006) Shame-focused regulation: An empirical study of the Compass of Shame Scale. Social Behavior and Personality 34: 161-168.

- Nathanson DL (1992) Shame and pride. New York: Norton.

- Dempster AP, Laird NM, Rubin DB (1977) Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B (Methodological) 39: 1-38.

- Levy KN (2012) Subtypes, dimensions, levels, and mental states in narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder. J Clin Psychol 68: 886-897. [Crossref]

- Pincus AL, Lukowitsky MR (2010) Pathological narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 6: 421-446. [Crossref]

- Andrews DA, Bonta J (2010) The psychology of criminal conduct (5thedn) New Providence, NJ: LexisNexis.

- Gabbard GO (2014) Psychodynamic Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. (5thedn.) Washington/London: American Psychiatric Press.

- Ronningstam EF (2009) Narcissistic personality disorder: facing DSM-V. Psychiatr Ann 39: 11-121.

- Shulman EP, Cauffman E, Piquero AR, Fagan J (2011) Moral disengagement among serious juvenile offenders: A longitudinal study of the relations between morally disengaged attitudes and offending. Dev Psychol 47: 1619-1632. [Crossref]