Abstract

Background: The association between migration and mental health remains unclear. To ensure an adequate health care of migrants, differentiated information on the association between migration and mental disorders is necessary.

Method: Cross-sectional study on depression and anxiety symptoms of people migrated to Germany from Turkey, Italy, and Spain as well as ethnic Germans repatriated from the states of the former Soviet Union (n=435). Depression and anxiety symptoms were measured with the Patient Health Questionnaire scales offered both in German and native language. Questionnaires were distributed by non-health-specific counselling agencies from welfare associations and migrants’ self-organisations.

Results: High rates of anxiety (23.0%) as well as depression (15.8%) were found. The Turkish migrants reported the highest level of symptoms, while the Spanish migrants the lowest. Logistic regression analyses showed that retired migrants with lower school qualifications and who report lower subjective wellbeing in Germany have a higher probability of suffering from anxiety or depression. Severity of depressive symptoms varied across cultures, showing the highest likelihood of symptoms for the Turkish migrants.

Conclusion: Our results suggest that migrants in Germany have a high risk of suffering from anxiety and depression. Cultural background is an independent predictor for depression but not for anxiety.

Key words

depression, anxiety, transcultural, migrants, cultural background

Introduction

Increasing globalization and the emergence of multicultural societies gives rise to the necessity to include cultural aspects in health care to a stronger degree. Considering that older migrants are among the most strongly growing population groups in Germany and prevalence of mental health disorders is continuously high [1], the socio-political significance of adequate health care in this population group is evident.

With regard to mental health, culture and migration related differences can be discerned above all with respect to how symptoms are experienced and dealt with [2-4]. Migrants are disadvantaged in terms of mental health care compared to natives in many respects [5-7]. Although the consideration of migration-related aspects is of great importance for an optimal care of migrants, there continues to be a lack of health care relevant investigations that take into account both the migration and the cultural background [5,8]. This leads to deficits in terms of misdiagnoses and inadequate treatments [9,10]. Empirical results on the prevalence of mental disorders in migrants are highly inconsistent. Some studies reported increased prevalence rates of mental disorders [11,12], while other studies did not find significant differences [13,14]. In summary, it can be assumed that acculturation difficulties increase the risk of mental disorders, and ethno-cultural values and attitudes as well as migration-related factors impede the utilization of health services [14-17]. Therefore, a transcultural perspective is essential for the understanding of the health situation of migrants. The aim of the study was a comparative cultural analysis of depression and anxiety syndromes as well as to examine the influence of socio-demographic, cultural, and migration-related factors on depression and anxiety in migrants in Germany.

Methods

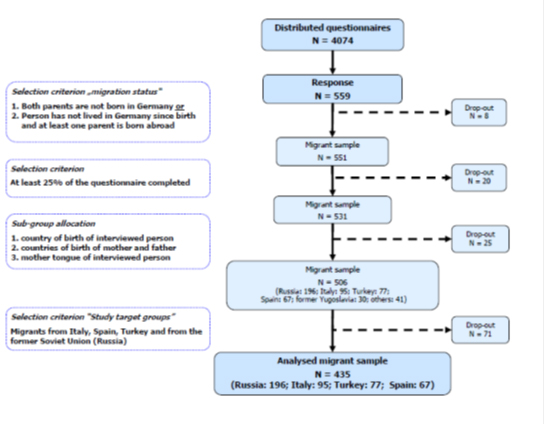

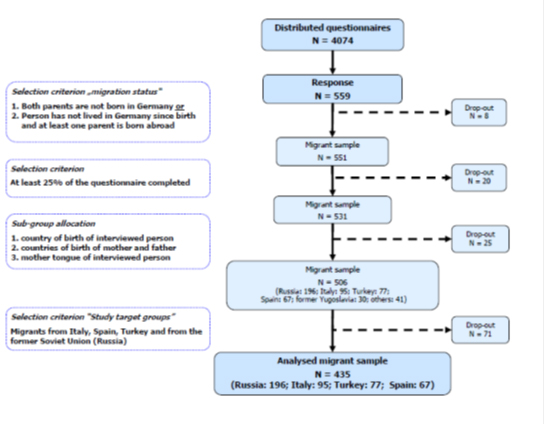

Within a cross-sectional survey, we asked migrants from Turkey, Italy, Spain and ethnic German repatriates from the states of the former Soviet Union about their mental health symptoms, social and occupational situation, as well as migration background. The survey was part of the study “Primary prevention of alcohol-related disorders in older migrants – development and evaluation of a transcultural prevention concept” (BMBF grant # 01 EL 071). The study aimed to gain information about mental health and the utilisation of the health care system in elderly migrants (over 45 years). Questionnaires and a prepaid reply envelope were distributed by non-health-specific counselling services from German Caritas Association (DCV) and Workers’ Welfare Federal Association (AWO) as well as self-help organisations and socio-cultural groups of migrants. In total, 4074 questionnaires were distributed (Figure 1). The overall response rate of 13.7% (n= 559) is consistent with the commonly high drop-out rates in studies with migrants [18,19]. For analysis, we identified people with a migration background (i.e., parents are not born in Germany or the person has not lived in Germany since birth and at least one parent was born abroad). Subsequently, participants were assigned to one of the study-relevant migrant groups (criteria: “country of birth of person”, “countries of birth of mother and father” or “mother tongue of person”). The analysed sample consisted of 435 migrants (n=196 repatriated Germans, n=95 Italian, n=77 Turkish and =67 Spanish) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Patient flow.

Measurements

Depression was measured with the “Patient Health Questionnaire” (PHQ-D) [20] and anxiety with the “Generalised Anxiety Disorder Scale” (GAD-7) [21]. Additionally, cultural aspects (mother tongue, countries of birth of subject, as well as his mother and father), migration-related factors (German language proficiency, wellbeing in Germany, length of stay in Germany) and socio-demographic characteristics (age, gender, school qualification) were assessed with the set of indicators for migrant status [22] and the “socio-demographic data inventory” [23]. The questionnaire was translated into Russian, Italian, Spanish and Turkish by two bilingual translators for each language, with these versions then being amalgamated by a third bilingual expert. Translation differences were resolved by the three translators and the translated versions than adapted in focus groups with migrants with a Russian, Italian, Spanish and Turkish background concerning comprehensibility and functional equivalence.

Data analysis

According to manuals, scores were computed for depression (PHQ-D-Score ≥11= major depressive disorder) and anxiety (GAD-7-Score ≥10=generalised anxiety disorder) [21,24]. Based on the level of data, t-tests, univariate analyses of variance with Scheffé post-hoc tests (interval or Likert-scaled variables) and Chi²-tests (categorical variables) were used for group comparisons. A two-sided significance level of p<.05 was used throughout. A logistic regression analysis was performed with depression (PHQ-D-Score ≥11) and anxiety (GAD-7-Score ≥10) as dichotomized outcomes including central influencing factors as independent variables: “level of school-leaving qualifications“ (no graduation; general secondary school; intermediate secondary school; higher education qualification), “gender”, “German language proficiency” (5-point Likert-scale; “very good“ to “very poor”), “cultural background” (Spain; Italy; Russia; Turkey), “wellbeing in Germany” (5-point Likert-scale; “very happy“ to “very unhappy“) “age”, and “length of stay in Germany” (years). All analyses were conducted using the SPSS software package (Version 17.0).

Results

As seen in table 1, the ratio of women (55.5%) and men (44.5%) was nearly even, except in the repatriated German group, where significantly more women participated in the study. The average age was 54.7 years. The oldest respondents were found in the Spanish and the repatriated German group, and the youngest in the Italian group. About 40% of the participants had a higher school education, with the Spanish and the repatriated German respondents having the highest and the Turkish and Italian respondents the lowest qualifications. Regarding employment, the highest number of unemployed persons was found in the repatriated German sample, whereas most participants in the other subgroups were employed. Overall, retired persons constituted the second largest group. Most of the respondents were married (68.9%), but a considerable number of Italian respondents were single and a substantial proportion of the Turkish respondents were divorced (Table 1).

Table 1. Sample.

|

|

|

|

Study sample |

|

|

|

Reference sample a |

|

|

|

|

Total |

Spain |

Italy |

Repatriates b |

Turkey |

Sig. |

Total |

Spain |

Italy |

Repatriates b |

Turkey |

|

|

|

(n= 435) |

(n= 67) |

(n=95) |

(n=196) |

(n=77) |

diff. § |

(n=5026c) |

(n=51c) |

(n=297c) |

(n=1.087c) |

(n=652c) |

|

Socio-demographic factors |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Age1 |

|

54.7 (12.4) |

56.6 (11.3) |

51.4 (13.5) |

56.3 (12.4) |

53.1 (11.0) |

R > I |

59.7 |

60.4 |

58.6 |

59.3 |

57.8 |

|

Gender2 |

Female |

55.5 |

49.3 |

41.1 |

65.6 |

51.9 |

< .001 |

50.8 |

49.0 |

37.0 |

53.9 |

48,0 |

|

School-leaving |

Basic |

35.2 |

28.3 |

44.1 |

28.6 |

52,9 |

.004 |

40.6 |

54.9 |

51.7 |

45.4 |

33,6 |

|

qualification2# |

Intermediate |

19.4 |

13.2 |

20.3 |

20.5 |

21,6 |

.658 |

15.8 |

9.8 |

10.5 |

31.0 |

5,7 |

|

|

High |

36.4 |

50.9 |

5.1 |

49.1 |

17,6 |

≤ .0001 |

23.7 |

13.7 |

7.8 |

15.2 |

6,9 |

|

|

None |

9.0 |

7.5 |

30.5 |

1.9 |

7,8 |

≤ .0001 |

19.4 |

19.6 |

29.4 |

17.4 |

53,4 |

|

Employment |

Employed |

32.2 |

43.3 |

49.5 |

17.9 |

37.7 |

< .0001 |

45.0 |

43.1 |

51.2 |

51.8 |

32,7 |

|

status2 |

Unemployed |

24.1 |

3.0 |

13.7 |

39.3 |

16.9 |

< .0001 |

6.6 |

2.0 |

6.7 |

8.2 |

7,5 |

|

|

Retired |

27.1 |

37.3 |

22.1 |

25.0 |

29.9 |

.140 |

32.4 |

37.3 |

30.0 |

29.0 |

33,4 |

|

|

Homemaker |

12.0 |

14.9 |

13.7 |

9.7 |

13.0 |

.602 |

n.d. |

n.d. |

n.d. |

n.d. |

n.d. |

|

Family status2 |

Married |

68.9 |

72.3 |

59.6 |

71.4 |

71.1 |

|

74.1 |

72.5 |

74.1 |

78.9 |

83,6 |

|

|

Single |

10.5 |

10.8 |

23.4 |

6.3 |

5.3 |

|

5.8 |

11.8 |

9.1 |

2.4 |

2,1 |

|

|

Divorced |

10.3 |

10.8 |

9.6 |

8.3 |

15.8 |

.001 |

9.6 |

n.d. |

10.1 |

7.0 |

6,4 |

|

|

Widowed |

10.3 |

6.2 |

7.4 |

14.1 |

7.9 |

|

10.5 |

n.d. |

6.7 |

11.7 |

7,7 |

|

Migration-related factors |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Length of stay in Germany1 |

18.6 |

29.9 (12.8) |

29.9 |

6.2 |

29.1 (10.3) |

I, T, E > R |

28.4 |

38.8 |

36.1 |

15.5 |

33.1 |

|

|

|

(15.1) |

|

(13.8) |

(4.6) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Wellbeing in Germany† |

3.77 |

4.12 |

3.92 |

3.59 |

3.70 |

E > T, R |

n.d. |

n.d. |

n.d. |

n.d. |

n.d. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

(0.73) |

(0.73) |

(0.63) |

(0.65) |

(0.92) |

I > R |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

German language |

3.32 |

3.91 |

3.66 |

2.95 |

3.32 |

E, I, T > R |

n.d. |

n.d. |

n.d. |

n.d. |

n.d. |

|

proficiency1‡ |

|

(1.00) |

(0.92) |

(0.80) |

(0.97) |

(0.98) |

E > T |

|

a data from the German Federal Statistical Office regarding immigrants older than 45 years; b ethnic Germans repatriated from territories of the former Soviet Union; c thousands; § unifactorial analysis of variance with Scheffé test (α = .05), E= Spain; I= Italy; R= repatriated Germans from territories of former Soviet Union; T= Turkey; respective Chi² test; 1 means (standard deviation); 2 percentage; # basic= elementary school; intermediate = secondary school; high= higher school graduation; † subjective assessment, Likert scale 1=“very unhappy” to 5=“very happy“; ‡ subjective assessment, Likert scale 1=“very poor” to 5=“very good “; n.d. no data or information available.

Regarding the duration of stay in Germany, there was a clear difference between repatriated German respondents, with 6.2 years, and the other subgroups, with nearly 30 years. Concerning the wellbeing regarding living in Germany, the Spanish respondents were the group with the most positive assessments, followed by Italians, whereas repatriated German and Turkish respondents reported only moderate wellbeing in Germany at average. Most of the participants reported good language proficiency, with Spanish respondents having the highest and repatriated German participants the lowest German language proficiency.

Compared with a reference sample [25], the education level was noticeably higher in the study sample, with the exception of the Italian group. Regarding the employment status, we found more unemployed persons in the Turkish and the repatriated German study sample than in the corresponding reference populations. Furthermore, fewer persons were married in the Italian and Turkish study sample. More repatriated German women participated in the study, and the duration of stay was lower in the repatriated German study sample than in the reference population.

Mental health

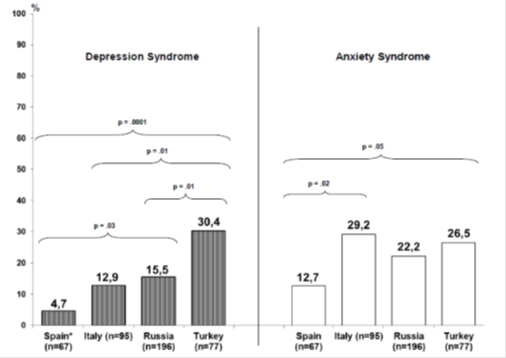

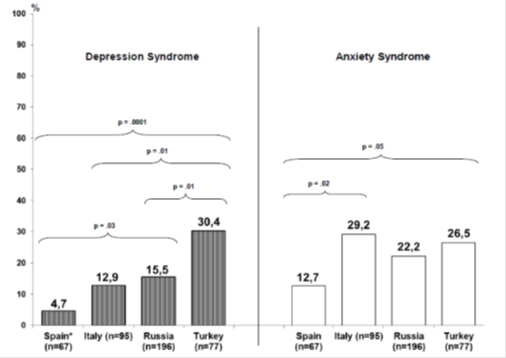

Regarding mental health symptoms, we found overall high rates of anxiety (23.0%) as well as of depression (15.8%). As seen in Figure 2, we also found significant subgroup differences. The Italian group shows with 29.2% he highest rates for anxiety followed by the Turkish (26.5%) and repatriated German group (22.2%). The lowest rates were shown by the Spanish group (12.7%). The difference between Spanish respondents on the one hand and Italian or Turkish respondents on the other hand was statistically significant with regard to the presence of a anxiety disorder (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Cultural background and mental health syndromes.

n= 435; depression syndrome: PHQ > 11; anxiety syndrome: GAD-7 > 10

More pronounced significant differences were found regarding depression. The highest rates of depression were shown by the Turkish respondents (30.4%), followed by repatriated Germans (15.58%) and the Italian group (12.9%). The lowest rates were found in the Spanish (4.7%). Concerning depression, we found significant differences nearly between all subgroups, with the Spanish respondents having a significantly lower rate than repatriated Germans or Turkish respondents. The Turkish respondents also had significantly higher depression rates than the Italians and repatriated Germans.

Predictors of anxiety and depression

Regarding anxiety, about 32% of the variation was explained by the considered variables (Table 2). Being a pensioner increases the odds of having an anxiety disorder by a factor of 3.7 compared with being employed. Conversely, people who have graduated from high school (odds ratio: .15) or are younger (odds ratio: .95) have reduced odds of having an anxiety disorder. Moreover, higher subjective wellbeing in Germany reduces the probability of anxiety (odds ratio: .21). No significant predictive value was found for cultural background.

Table 2. Factors influencing the presence of mental health disorders (Logistic regression: method: enter).

|

|

|

Anxietya |

|

|

Depressionb |

|

|

Bc |

Sig |

OR |

95%CI OR |

B‡ |

Sig |

OR |

95%CI OR |

Independent variables |

|

|

|

low |

upper |

|

|

|

low |

upper |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cultural background |

|

.634 |

|

|

|

|

.006 |

|

|

|

Ref.: Turkey |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Spain |

-.466 |

.488 |

.627 |

.168 |

2,345 |

-3.141 |

.005 |

.043 |

.005 |

.393 |

Italy |

.297 |

.593 |

1.345 |

.453 |

3,996 |

-1.655 |

.011 |

.191 |

.053 |

.686 |

Russiad |

-.409 |

.535 |

.664 |

.182 |

2,423 |

-1.517 |

.030 |

.219 |

.056 |

.865 |

Socio-demographic variables |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Age (years) |

-.055 |

.007 |

.946 |

.909 |

,985 |

-.027 |

.199 |

.973 |

.933 |

1.014 |

Gender |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ref.: female |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

male |

-.594 |

.114 |

.552 |

.264 |

1,154 |

-.375 |

.386 |

.687 |

.294 |

1.607 |

School qualificatione |

|

.066 |

|

|

|

|

.026 |

|

|

|

Ref.: no certificate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Basic |

-1.186 |

.066 |

.306 |

.086 |

1,084 |

-1.468 |

.062 |

.230 |

.049 |

1.074 |

Intermediate |

-1.246 |

.071 |

.288 |

.074 |

1,113 |

-1.067 |

.187 |

.344 |

.070 |

1.681 |

High |

-1.877 |

.008 |

.153 |

.038 |

,619 |

-2.259 |

.008 |

.104 |

.020 |

.552 |

Employment status |

|

.087 |

|

|

|

|

.011 |

|

|

|

Ref.: employed |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Unemployed |

.384 |

.438 |

1.469 |

.556 |

3,881 |

-.339 |

.565 |

.712 |

.224 |

2.263 |

Retired |

1.313 |

.019 |

3.718 |

1.236 |

11,187 |

1.614 |

.009 |

5.024 |

1.500 |

16.820 |

Homemaker |

-.436 |

.513 |

.647 |

.175 |

2,388 |

.701 |

.332 |

2.016 |

.488 |

8.318 |

Family status |

|

.693 |

|

|

|

|

.668 |

|

|

|

Ref.: married |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Single |

-.907 |

.258 |

.404 |

.084 |

1,945 |

.670 |

.407 |

1.955 |

.401 |

9.529 |

Divorced |

-.289 |

.603 |

.749 |

.252 |

2,223 |

.546 |

.353 |

1.727 |

.545 |

5.477 |

Widowed |

-.017 |

.975 |

.983 |

.345 |

2,805 |

.355 |

.532 |

1.427 |

.468 |

4.350 |

Migration-related variables |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Years in Germany |

-.002 |

,937 |

,998 |

.957 |

1,042 |

-.031 |

.197 |

.970 |

.926 |

1.016 |

Wellbeing in Germanyf |

-1.562 <.001 |

.210 |

.121 |

,364 |

-1.213 <.001 |

.297 |

.169 |

.524 |

German language proficiencyg |

-.003 |

.989 |

.997 |

.653 |

1,523 |

.295 |

.232 |

1.344 |

.828 |

2.181 |

Nagelkerkes -R²: |

|

|

.324 |

|

|

|

|

.355 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

a Anxiety disorder: GAD-7 ≥ 10; b Depressive disorder: PHQ ≥ 11; c B = regression coefficient (Beta); Sig.= p-value of the Wald test statistic; OR= odds ratio or exponentiated Beta coefficient; 95%CI OR= 95% confidence interval; lower and upper value of the exponentiated Beta coefficient; d ethnic Germans repatriated from the states of the former Soviet Union; Ref. reference category; e basic= elementary school; intermediate = secondary school; high= higher school graduation; f “How happy do you feel living in Germany?” Likert scale: 1=“very unhappy” to 5=“very happy“; g subjective assessment, Likert scale: 1=“very poor” to 5=“very good “

With regard to depression, about 36% of the variation was explained by the predictors. Pensioners have a 5.0 times higher likelihood of having a depressive disorder than employed people. On the other hand, increased wellbeing in Germany (odds ratio: .30) and a higher level of school graduation reduces the probability of a depressive disorder compared with having no school leaving certificate (odds ratio: .10). With respect to cultural background, we found that Spanish migrants (odds ratio: .04), Italian migrants (odds ratio: .19) as well as repatriated Germans (odds ratio: .22) have a lower probability of reporting a depressive disorder compared with Turkish migrants. Therefore, the likelihood of a considerably severe depression was 80 to 100% higher for respondents with a Turkish background compared to respondents with other cultural backgrounds (Table 2).

Discussion

Although migrants have been part of German society for many years, they are still disadvantaged in health care, particularly with regard to mental health care [5,25]. The lack of studies that take into account both the migration and the cultural background leads to deficits in the health care of this group. Thus, to ensure an adequate health care of migrants, differentiated information on the association between migration background and mental disorders is needed. The aim of this study was to analyse the occurrence of depressive and anxiety syndromes in migrants depending on socio-demographic, cultural, and migration-related factors.

Corresponding to the different migration processes of the analysed groups described in literature [26], we found significant subgroup differences in socio-demographic and migration-related factors. Spanish persons had the highest average age and the highest education level, whereas Italian respondents were the youngest and had the lowest education level. On average, the repatriated German respondents had lived in Germany for six years, while all other subgroups had lived in Germany for nearly 30 years. The Spanish respondents had the highest and the repatriated German participants the lowest subjective German language proficiency. Altogether, most respondents reported an at least fair wellbeing in Germany. A comparison of the examined sample with a reference sample showed that a higher education level and higher rates of unemployed persons as well as retired persons are present in the study sample. These differences in the socio-demographic and migration-related factors can be traced back to the varying migration histories of the examined migrant groups.

In comparison to what was expected from the German Health Survey [1,27] (four-week prevalence of affective disorders: 11.7% and 7.8% for anxiety disorders), we found in our study indications of higher levels of depressive and anxiety syndromes. Furthermore, subgroup comparisons demonstrated that the Turkish migrants showed the highest degrees of symptoms for both mental health complaints, whereas the Spanish migrants had the lowest degree of anxiety and depressive symptoms. These results are partly in line with the results from other migration-sensitive analyses of mental health, which reported increased prevalence rates of depressive disorders among migrants [28-31], but stands in contrast to other studies which did not find such high rates of anxiety and depressive disorders in migrants [4,10,13].

2021 Copyright OAT. All rights reserv

We analysed the association of depressive and anxiety syndromes with socio-demographic and migration-related factors as well as the cultural background. For both mental health disorders, we found a considerable degree of explained variation. Major factors that led to an increased probability for anxiety or depression were the fact of being retired, a lower level of school qualification and lower level of wellbeing in Germany. The cultural background was only a relevant factor explaining depressive symptoms, with the Turkish migrants showing a higher likelihood of having a depressive disorder. In contrast to other authors [2,32], we found no significant predictive value of acculturation indicators such as length of stay in Germany and German language proficiency. These results are partly in line with the results of studies in the Netherlands and Belgium, which report increased prevalence rates of depressive disorders among Turkish migrants [28,33]. This could be a reflection of cultural variation in idioms of distress and attitudes regarding mental complaints [34,35]. On the other hand, differences in help-seeking behaviour between migrant groups might also have influenced these results [14,29,36]. From the transcultural literature, it can be assumed that feelings of loss, culture-related values, expectations and attitudes, as well as the failure of achieving life goals may also codetermine the development of mental health disorders [2,5,8,37].

Limitations arise particularly from the small response rate not unusual in studies with migrants. Migrants frequently associate scientific surveys with government control and on the other hand, often have little reading and writing proficiency and therefore difficulties in completing questionnaires [18,38,39]. Since the response rate was low, it cannot be ruled out that our participants were highly interested and/or highly engaged migrants. Second, a selective distortion of the sample might have taken place both through the participating mediators (i.e. counselling agencies of welfare associations) and the migrants. Hence, results should be interpreted with caution, since the sample reflects only the situation of migrants with an affinity towards social and welfare environments. Still, the fact that the sample is fairly comparable to the corresponding general population migrant groups in Germany regarding several socio-demographic factors increases representativeness of the findings and reduces the probability of highly biased results. A third limitation results from the exclusively subjective assessment of mental health. However, several studies have shown appropriate validity of the used instruments [21,24]. Finally, we cannot dismiss the possibility that the results might be partly influenced by the difficulty of a transculturally reliable and valid assessment of mental disorders [15,40-43].

In summary, our results can be interpreted as a clear indication that the cultural background is an important independent factor regarding the emergence of mental health syndromes in migrants. Further specific research is needed regarding the impact of cultural and migration experiences on the occurrence of mental health disorders as well as on help-seeking behaviour of persons with non-native cultural backgrounds. This could lead to more knowledge about risk factors as well as about cultural and migration-related resources and characteristics that are beneficial for mental health.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the research funding program “Health research: research for the people – prevention research for health promotion and primary prevention in the elderly”, Project “Primary prevention of alcohol-related disorders among elderly immigrants – Developing and evaluating the trans-cultural prevention program” (Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF); grant # 01 EL 071). We would like to thank Daniela Ruf, Ilina Maier, Harald Pessentheiner (University Medical Center, Freiburg), Renate Walter-Hamann, Antonela Serio, Stefan Herceg (Deutscher Caritasverband, Freiburg), and Hedi Boss and Wolfgang Barth (AWO Bundesverband, Berlin) for their active collaboration in carrying out the project.

Declaration of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jacobi F, Höfler M, Siegert S, Mack S, Gerschler A, et al. (2014) Twelve-month prevalence, comorbidity and correlates of mental disorders in Germany: the Mental Health Modul of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey of Adults (DEGS1-MH). Int J Methods in Psychiatr Res 2014.

- Bhugra D (2005) Migration and mental health. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 109: 243-258.

- Machleidt W, Callies IT (2005) Migration and Transcultural Psychiatry - Mental illness from a ethical perspective [In German]. Psychiatrie 2: 77-84.

- Swinnen SG, Selten JP (2007) Mood disorders and migration: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 190: 6-10. [ Crossref]

- Bermejo I, Muthny FA (2009) Conclusion and recommendations for the healthcare system of a multicultural society [In German] In: Muthny FA, Bermejo I (Hrsg): Cross-cultural aspects of medicine - lay theories, Psychosomatics and consequences of migration. Köln: Deutscher Ärzte-Verlag: 139-144.

- Deville W, Greacen T, Bogic M, Dauvrin M, Dias S, et al. (2011) Health care for immigrants in Europe: is there still consensus among country experts about principles of good practice? A Delphi study. BMC Public Health 11: 699.

- Wittig U, Lindert J, Merbach M, Brähler E (2008) Mental health of patients from different cultures in Germany. Eur Psychiatry 23 Suppl 1: 28-35. [Crossref]

- Kirkcaldy B, Wittig U, Furnham A, Merbach M, Siefen RG, et al. (2006) Health and migration. Psychosocial determinants. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 49: 873–883.

- Claassen D , Ascoli M, Berhe T, Priebe S (2005) Research on mental disorders and their care in immigrant populations: a review of publications from Germany, Italy and the UK. Eur Psychiatry 20: 540-549. [Crossref]

- Schraufnagel TJ, Wagner AW, Miranda J, Roy-Byrne PP (2006) Treating minority patients with depression and anxiety: what does the evidence tell us?. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 28: 27-36. [Crossref]

- Cantor-Graae E , Selten JP (2005) Schizophrenia and migration: a meta-analysis and review. Am J Psychiatry 162: 12-24. [Crossref]

- Kirkbride JB , Barker D, Cowden F, Stamps R, Yang M, et al. (2008) Psychoses, ethnicity and socio-economic status. Br J Psychiatry 193: 18-24. [Crossref]

- Glaesmer H, Wittig U, Brähler E, Martin A, Mewes R, et al. (2009) Are migrants more often affected by mental disorders? A study on a representative sample of the German general population [In German]. Psychiatrische Praxis 36: 16-22.

- Lay B, Lauber C, Rössler W (2005) Are immigrants at a disadvantage in psychiatric in-patient care? Acta Psychiatr Scand 111: 358-366. [Crossref]

- Bermejo I, Ruf D, Mösko M, Härter M (2010b) Epidemiology of mental disorders among migrants [In German]. In: Machleidt W, Heinz A, (Hrsg.): Practice of cross-cultural psychiatry and psychotherapy. Migration and Mental Health. München: Urban & Fischer: 209-215.

- Fortier JP (2010). Migrant-sensitive health systems. In: Health of Migrants – The way forward. Report of a global consultation. Madrid, Spain, 3-5 March 2010. WHO

- Lindert J , Schouler-Ocak M, Heinz A, Priebe S (2008b) Mental health, health care utilisation of migrants in Europe. Eur Psychiatry 23 Suppl 1: 14-20. [Crossref]

- Razum O, Zeeb H, Meesmann U, Schenk L, Bredehors M, et al. (2008) Balance Report of the Federal Health Reporting - Migration and Health [In German]. Berlin, Germany: Robert Koch-Institut.

- Schenk L, Neuhauser H (2005) Methodological standards for migrant-sensitive research in epidemiology. [In German]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt – Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz 48: 279–286.

- Löwe B, Spitzer RL, Zipfel S, Herzog W (2002) PHQ-D Health questionnaire for patients [In German]. Karlsruhe

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B (2006) A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 166: 1092-1097.

- Schenk L, Bau AM, Borde T, Butler J, Lampert T, et al. (2006) Minimum set of indicators for measuring the migration status. Recommendations for epidemiological practice [In German]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 49: 853–860.

- Jöckel KH, Babitsch B, Bellach BM, Bloomfield K, Hoffmeyer-Zlotnik J, et al. (1997) Measurement and quantification of socio-graphic characteristics in epidemiological studies: recommendations of the Deutschen Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Epidemiologie (DAE) der GMDS und DGMSP [In German].

- Löwe B, Spitzer RL, Gräfe K, Kroenke K, Quenter A, et al. (2004) Comparative validity of three screening questionnaires for DSM-IV depressive disorders and physicians’ diagnosis. Journal of Affective Disorders 78: 131–40.

- Statistisches Bundesamt (2011) Specialist Series 1 Series 2.2. Population and employment. Population with a migration background - Results of the micro-census 2009. Special report oft the German Federal Statistical Office regarding immigrants older than 45 years on demand of the University Medical Centre Freiburg, Department for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy [In German].

- Bermejo I (1999). Spaniards in Germany - life situation, problems, needs support [In German]. Caritas Korrespondenz 67: 19-34.

- Bermejo I, Mayninger E, Kriston L, Härter M (2010a) Mental disorders in people with a migration background in comparison to the German general population [In German]. Psychiatrische Praxis 37: 225–232.

- De Wit MAS, Tuinebreijer WC, Dekker J, Beekman AJTF, Gorissen WHM, et al. (2008) Depressive and anxiety disorders in different ethnic groups. A population based study among native Dutch, and Turkish, Moroccan and Surinamese migrants in Amsterdam. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 43: 905–912.

- Lindert J, Brähler E, Wittig U, Mielck A, Priebe S, et al. (2008a) Depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorders in labor migrants, asylum seekers and refugees [In German]. Psychotherapie Psychosomatik Medizinische Psychologie 58: 109-122.

- Sieberer M , Maksimovic S, Ersöz B, Machleidt W, Ziegenbein M, et al. (2012) Depressive symptoms in first-and second-generation migrants: a cross-sectional study of a multi-ethnic working population. Int J Soc Psychiatry 58: 605-613. [Crossref]

- Weich S, Nazroo J, Sproston K, MCManus S, Blanchard M, et al. (2004) Common mental disorders and ethnicity in England: the EMPIRIC study. Psychological Medicine 34:1543–1551.

- Wiking E, Johansson SE, Sundquist J (2004) Ethnicity, acculturation, and self reported health. A population based study among immigrants from Poland, Turkey, and Iran in Sweden. J Epidemiol Community Health 58: 574-582. [Crossref]

- Levecque K , Lodewyckx I, Vranken J (2007) Depression and generalised anxiety in the general population in Belgium: a comparison between native and immigrant groups. J Affect Disord 97: 229-239. [Crossref]

- Raguram R , Weiss MG, Channabasavanna SM, Devins GM (1996) Stigma, depression, and somatization in South India. Am J Psychiatry 153: 1043-1049. [Crossref]

- Kirmayer LJ, Sartorius N (2007) Cultural models and somatic syndromes. Psychosom Med 69: 832-840. [Crossref]

- Tiwari SK, Wang JL (2008) Ethnic differences in mental health service use among White, Chinese, South Asian and South East Asian populations living in Canada. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 43: 866–871.

- Thapa SB, Hauff E (2005) Gender differences in factors associated with psychological distress among immigrants from low and middle-income countries. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 40: 78–84.

- Mielk A (2000) Social inequality and health. Empirical results, explanations, intervention possibilities [In German]. Göttingen, Germany: Verlang Hans Huber.

- Schenk L (2002) Migrant-Specific Respondent Hurdles and Access Opportunities in the National Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents [In German]. Das Gesundheitswesen 64: 59-79.

- Zeeb H, Razum O (2006) Epidemiological research on migrant health in Germany. An overview [In German]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 49: 845–885.

- Bermejo I, Maier I, Ruf D, Pessentheiner H, Walter-Hamann R, et al. (2009) Barriers for migrants in the use of health measures [In German]. In: Schneider, F., Grözinger, (Hrsg.) Mental illness in the life span. Abstractband zum DGPPN Kongress 25- 28. November, Berlin. Berlin, DGPPN: 449.

- Bhugra D (2006) Severe mental illness across cultures. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 113 Suppl. 429: 17-23.

- Raguram R, Weiss MG, Channabasavanna SM, Devins GM (1996) Stigma, depression, and somatization in South India. Am J Psychiatry 153: 1043-1049. [Crossref]