Abstract

Objective: To quantitatively and qualitatively describe specific barriers encountered by Maternal-Fetal Medicine (MFM) subspecialists to providing second-trimester termination by dilation and evacuation (D&E) using a mixed methods approach.

Methods: We surveyed all members of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, and all faculty and fellows associated with MFM fellowships regarding practice characteristics and barriers to second-trimester termination. We categorized barrier responses into five categories: lack of training, logistical issues, negative culture, personal issues and no barriers. We compared respondent characteristics across barrier categories. We qualitatively analyzed barrier-related themes from respondents’ comments using a grounded theory approach.

Results: Of the 689 (32%) physicians who completed the survey, 591 (86%) reported at least one barrier to D&E provision. Main barriers among D&E providers (n=216) and D&E non-providers (N=473) differed, with providers reporting negative culture (37%) and logistical issues (33%) and non-providers reporting personal issues (36%) and lack of training (28%). Qualitative themes related to practice barriers paralleled the above categories.

Conclusion: Addressing logistical barriers faced by D&E providers may streamline D&E services. Establishing routine D&E training in MFM fellowships is critical for supporting MFMs who wish to provide D&E. Collaborative partnerships with family planning subspecialists may facilitate this process.

Key words

abortion, abortion providers, maternal-fetal medicine

Introduction

In 2011 there were an estimated 1.06 million induced abortions[1], making abortion one of the most common medical procedures in the US. Dilation and evacuation (D&E) and induction termination are both safe and effective methods of second-trimester abortion[2]. D&E is faster, more predictable, more cost-effective, has a lower complication rate, and is associated with higher patient acceptability as compared to induction termination[3-7]. However, because of the inadequate number of D&E providers in the U.S., many women do not have timely access to D&E[8]. An estimated 87% of counties in the US do not have a trained D&E provider[9]. Only half of obstetrics and gynecology residency training programs routinely teach abortion, and only 18% of residents receive training in D&E[10].Furthermore, only one in five abortion providers performs D&E after 20 weeks [8]. Limited access leads to a delay in presentation for care[11],the downstream effects of which include higher risk of complications[12]and increased cost of providing care[8].

More than 2,000 Maternal-Fetal Medicine (MFM) subspecialists practice in the US, and nearly one-third of them report that they provide D&E [13]. The decision to include D&E in their scope of practice is likely related to practice setting, desire for continuity of care with patients, institutional culture, and training. Family planning (FP) subspecialists most frequently report unsupportive nursing staff, logistical issues, and unsupportive administration as barriers to D&E provision[14]. Given the training and practice differences between MFMs and FPs, MFMs may encounter different barriers to D&E provision.

The primary aim of this study is to elucidate the specific barriers MFMs encounter in providing D&E using a mixed methods approach. By identifying barriers for D&E providers and non-providers, we will be able to develop specific, targeted interventions that support and encourage MFMs who want to offer D&E services to their patients.

Materials and methods

We conducted a survey in 2010 of all US members of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM), and all faculty and fellows associated with MFM fellowships. We obtained names and postal addresses for SMFM members from SMFM and other fellowship-affiliated physicians from the American Board of Obstetricians and Gynecologists subspecialty handbook and by searching institutional websites. We sent an email invitation to all subjects to complete the web-based survey using Key Survey. Subjects without a publicly available email address received a paper survey, but were also given the option to complete the web-based survey. Email invitees received three emails to complete the survey, each one week apart. Paper invitees received one mailing with the survey and one reminder postcard.

The survey included 65 questions about demographics and practice characteristics, training in and provision of second-trimester termination, institutional regulations on termination of pregnancy and barriers to offering second-trimester termination, and an optional comment section. We offered respondents a $5 gift card that was not contingent upon starting or completing the survey. To ensure anonymity, respondents were only asked to identify the region of the US and population size of the city where they practice. We asked physicians about trainees and characteristics related to practice setting. We assessed intrinsic religious motivation using three validated questions with true or false responses.15Scores ranged from 0 to 3, with higher scores reflecting greater religious motivation. We assessed abortion attitudes using a validated scale with five questions on a five-point Likert scale[16]. Scores ranged from 5-25, with higher scores reflecting more favorable abortion attitudes.

We asked respondents to report the number of D&Es they performed in the past year. Provision of D&E was defined as performing or supervising at least one procedure in the last year. We then gave physicians a list of barriers and asked them to identify all barriersand the main barrierin providing D&Es. We categorized the main barrier responses into five main barrier categories: (a) lack of training, (b) logistical issues (done by others, insurance reasons, no back up, other logistical reasons), (c) negative culture (unsupportive colleagues or administration, restrictive environment, concern for safety, (d) personal issues (personal preference or objection for any reason, e.g. religion)and (e) no barriers.

We used descriptive statistics to compare baseline characteristics among barrier categories and all main barriers using chi-square, Fisher’s exact, or t-tests, as appropriate. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to estimate odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for correlates of MFMs reporting specific main barrier types. We included variables associated at a p<0.2 level in the unadjusted analysis in multivariable logistic regression models.

Respondents were asked to leave comments about their practices related to D&E provision and barriers related to that practice. Using grounded theory approach[17-19], we analyzed those open-ended comments for themes related to barriers to D&E practice. Three authors (JK, JT, LL) participated in the iterative process of coding and sorting the data, collapsing and expanding themes as the data were analyzed. We coded by hand, using memos to explore and analyze themes from the data. The University of California, San Francisco Committee on Human Research approved this study.

Results

We identified 2125 physicians as SMFM members, MFM fellows, or MFM fellowship faculty. We sent email invitations to nearly half of all MFMs (n=905, 43%) and we mailed paper surveys to the remaining (n=1220, 57%). A total of 689 physicians (32%) completed the surveys. Physicians invited by e-mail were more likely to complete the survey (401/905) compared with those invited by mail (288/1220; p < 0.001). Of the 288 respondents who were invited by mail, 32% chose to complete the survey online instead of on paper.One-third of respondents report providing D&E, half of whom provide beyond 20 weeks and the majority of whom were trained during residency (69%) (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of respondents.

Demographics |

N (%)a |

Total |

689 |

Age, mean (SD) |

47.1 (10.1) |

Female |

355 (51.5) |

Region |

|

|

|

West |

174 (25.4) |

Northeast |

222 (32.4) |

South/Southeast |

158 (23.1) |

Midwest |

130 (19.0) |

Provides induction terminations |

473 (68.6) |

Number of induction terminations per year, median (SE) |

11 (0.9) |

Provides dilation and evacuation (D&E) terminations |

216 (31.3) |

Number of D&Es per year, median (SE) |

6 (1.6) |

Abortion attitudeb, mean (SD) |

16.8 (4.2) |

Intrinsic religious motivationc, mean (SD) |

0.66 (0.9) |

Practice Setting |

Population of practice city ≥ 1 million |

259 (39.6) |

Academic practice ≥ 50% time |

470 (68.4) |

Family Planning Fellowship at current institution |

143 (21.0) |

Works with trainees |

599 (87.1) |

When trained |

|

|

Residency |

265 (68.8) |

|

Fellowship |

106 (27.5) |

|

After fellowship |

14 (2.6) |

Up to what gestational age D&E is done |

|

|

<16weeks |

8 (3.7) |

|

16-20weeks |

106 (49.1) |

|

>20 weeks |

102 (47.2) |

Where patients access D&E |

|

|

My institution |

312 (46.2) |

|

Other |

363 (53.8) |

Setting of D&E services |

|

|

|

Hospital operating room |

175 (81.0) |

Labor & Delivery |

23 (10.7) |

Other outpatient center |

18 (8.3) |

aMean (SD) or median (SE) for continuous variables.

bScores range from 5-25, with higher scores reflecting attitudes more supportive of abortion.

cScores range from 0-3, with higher scores reflecting greater intrinsic religious motivation.

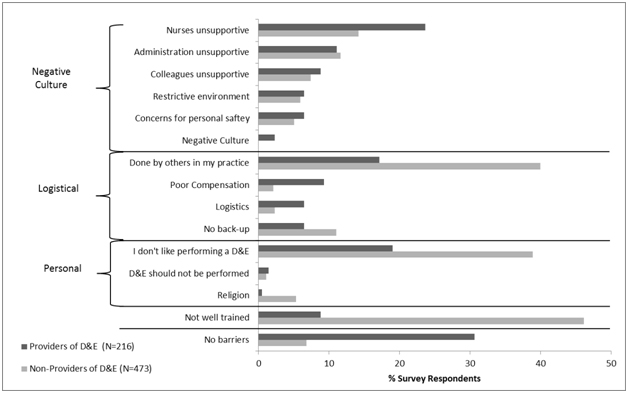

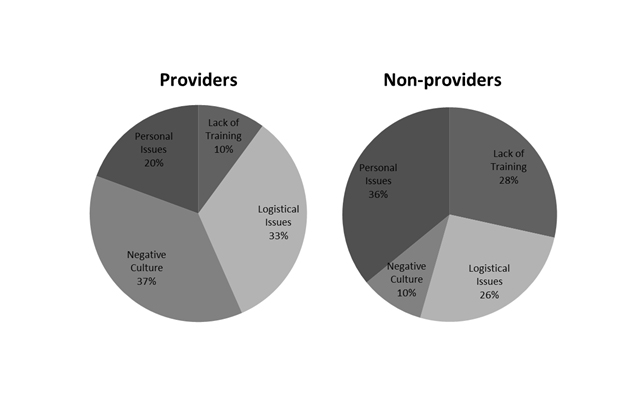

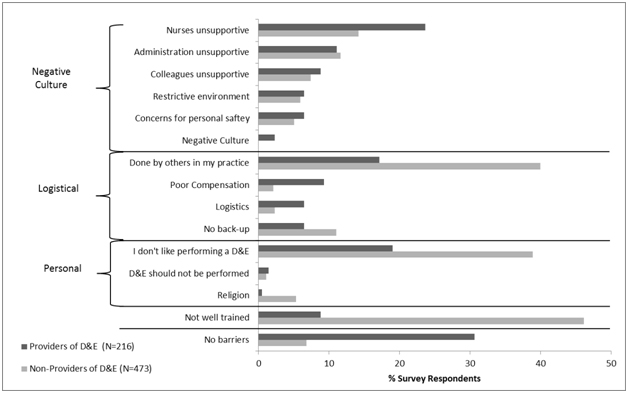

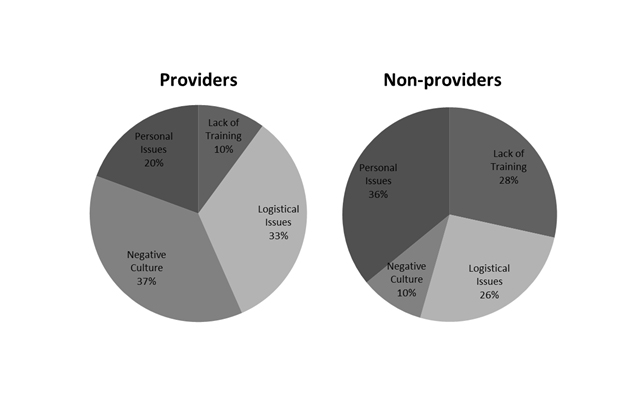

A majority of respondents (86%) report at least one barrier to D&E provision (Figure 1). Among the 216 D&E providers, one-third reports no barrier to provision. Both D&E providers and non-providers report D&Es being done by others and personal dislike for performing D&E as barriers. D&E providers report unsupportive nursing staff while non-providers report lack of training. When we grouped reported barriers into categories, the most frequently reported barriers among D&E providers were negative culture (59%) and logistical issues (40%). Non-providers report logistical issues (55%) and lack of training (46%), although nearly half also report personal issues and negative culture as barriers. When asked to identify their mainbarrier, D&E providers report negative culture and logistical issues most commonly (37% and 33%, respectively) while non-providers report personal issues and lack of training most commonly (36% and 28%, respectively) (Figure 2).

Figure 1. The proportions of D&E providers and non-providers who identified specific barriers grouped into categories of logistical, negative culture, and personal barriers.

Figure 2. Distributions of main barriers among providers and non-providers of D&E.

Barriers among D&E providers

In an unadjusted analysis of correlates of main barrier category among D&E providers, we found that those reporting no main barrier are more likely to be male than those reporting at least one main barrier (67% vs. 52%, p=0.04) while female gender is more common among those reporting lack of training (77% vs. 40%, p=0.01), logistical issues (60% vs. 38%, p=0.008) or personal issues (76% vs. 45%, p=0.04). Reporting lack of training as a main barrier is associated with younger age (39 vs. 45 years, p=0.01). D&E providers reporting personal issues have a less favorable abortion attitude than those reporting other main barriers (mean 15.3 vs. 18.0, p<0.001), while those reporting logistical issues have a significantly more favorable abortion attitude (mean 18.7 vs. 17.4, p=0.04). Of the thirteen providers who report lack of training as their main barrier, none is from the Western region. Finally, D&E providers reporting no barrier are less likely to work in an academic setting compared to those reporting other main barriers (64% vs. 80%, p=0.02), while providers reporting logistical issues are more likely to work in an academic institution and with FP fellowships (88% vs. 71%, p=0.05).

In adjusted analyses, age, religiosity and abortion attitude are independent predictors of main barrier category. Among D&E providers, lack of training is associated with younger age (OR 0.9, 95% CI 0.8-1.0). Logistical issues are associated with lower religiosity (OR 0.5, 95% CI 0.2-0.95) and personal issues are associated with less favorable abortion attitude (OR 0.9, 95% CI 0.8-0.97).

Barriers among D&E non-providers

In an unadjusted analysis of D&E non-providers, reporting no main barrier or logistical issues as the main barrier to providing D&E is associated with working at an institution with FP providers (p=0.01 and p<0.0001, respectively). Lack of training, negative culture or personal issues are associated with lower odds of working at an institution with FP fellows (p=0.04, p=0.01 and p=0.04 respectively). Abortion attitude varies significantly with reported main barrier. Logistical issues and lack of training are associated with more favorable abortion attitude (p<0.001 and p=0.02) while personal issues are associated with less favorable abortion attitude (p<0.001). Negative culture is associated with practicing in the Midwest (p=0.01) and logistical issues are associated with practicing in the West (p=0.04), but these associations do not persist in the adjusted analysis. Among D&E non-providers, there is significant variation in induction termination provision by main barrier type. Those reporting personal issues or negative culture provide significantly fewer induction terminations per year (5.1 vs. 7.2, p=0.05 and 3.2 vs. 6.8, p=0.04, respectively). Lack of training is associated with providing significantly more induction terminations per year (9.0 vs. 5.5, p=0.002).

In adjusted analyses among D&E non-providers, negative culture or lack of training is associated with lower odds of working with FP fellows [(OR 0.2, 95% CI 0.1-0.8) and (OR 0.4, 95% CI 0.2-0.7), respectively]. Conversely, logistical issues are associated with increased odds of working with FP fellows (OR 2.9, 95% CI 1.6-5.1). Lack of training is associated with lower religiosity (OR 0.6, 95% CI 0.4-0.9) whereas personal issues are associated with higher religiosity (OR 1.5, 95% CI 1.2-2.0) and less favorable abortion attitude (OR 0.9, 95% CI 0.8-0.9). Logistical issues are associated with older age(OR 1.0, 95% CI 1.0-1.1) and a more favorable abortion attitude (OR 1.1, 95% CI 1.0-1.2).Finally, negative culture is associated with providing fewer induction terminations per year (OR 0.9, 95% CI 0.9-0.99).

Of the 689 respondents, 127 (18%) wrote in comments about their D&E practices. Fifty-six of the 127 comments (44%) relate to barriers in providing D&E and the themes and representative quotes mirror the barrier categories described above (Table 2). Lack of training is frequently mentioned in respondents’ comments as a reason for never or rarely providing D&Es (Theme 1). One respondent highlights that training in residency is essential in order to offer these services post-residency (Q1). Respondents convey a sense of regret that they were not trained in residency, indicating that had they been trained, they would be able to provide this important service. Finally, a few comments address whether D&E should be within the scope of MFM training. One respondent seems overwhelmed by the idea of carrying the “sole burden” for providing D&Es (Q4). Another respondent (Q5) questions whether MFMs should be providing D&Es at all when they are less well trained than their FP colleagues.

Table 2. Open-ended comments regarding barriers to dilation and evacuation (D&E) provision.

Theme 1: Lack of Training |

Q1 |

I would like to do/supervise D&Es myself but my exposure during residency training was too low to safely offer this to my patients. |

Q2 |

…[training] is disappointingly not routine in MFM fellowship and the reality is that I will likely not be providing this service because of lack of keeping my skills up to date. |

Q3 |

My hospital admin is supportive but no other obstetricians are trained in D&E after 16 weeks. |

Q4 |

I personally do NOT feel that MFMs should have the sole burden of doing inductions or D&Es. I feel that there should be a 6-12 month fellowship for those who want to do this work. |

Q5 |

I don't think MFMs should be trained because we just don't see the numbers a [family planning] fellow would see. As long as a [fellowship trained family planning] provider is available, ethically I don't know/see how MFM can do D&Es. |

Theme 2: Logistical Issues |

D&Es are done by others |

Q6 |

In some institutions, there is compartmentalization of providing patient care, which may make it difficult for individuals other than family planning to provide care for performing D&E. |

Q7 |

We have one of our family planning guys who does the D&Es in a free standing surgical center. We can do them in the hospital but it's much more expensive for the patients so they usually go to this other center. |

Q8 |

At the local surgicenter get they a time a date and the process is efficient and cheaper than the institution but is staffed by mainly all of the same providers. |

Q9 |

Contract with Planned Parenthood to perform pregnancy terminations. We perform inductions in-house. |

Q10 |

Procedures are either referred to an MFM colleague (e.g. amnio, sono, CVS) or Family Planning colleague (e.g. D&E) even if I am trained to do all of these because of the way our department designates where we should apply our efforts. |

Insurance Limitations |

Q11 |

…insurance method limits options for termination services. D&Es are not readily available for Medicaid patients. |

Q12 |

Usually patients pick a D&E if their insurance doesn't cover the induction. |

Q13 |

…our main limitation to offering D&E is 1) our patients don't have insurance to pay for it, 2) we have 2 [trained providers of D&E] on staff, but they are frequently not available. |

Theme 3: Negative Culture |

Religious Institutional Restrictions |

Q14 |

Faith-based and taxpayer-funded hospitals frequently do not offer elective termination, but will treat women with indications such as anomalies, chorio, or prom. |

Q15 |

Catholic Hospital. We can do induction for severe preeclampsia and chorio (sepsis) as the Church has ruled that "to save the life of the mother, the placenta, which is causing the problem, must be delivered". |

Q16 |

Any termination that is required is done over at the University. I do all abnormalities at the Catholic institution that are considered lethal through a Medical Morals Committee. Ones that are not lethal go to the university. |

Q17 |

I practice at a Catholic hospital, so all elective terminations have to be referred out. |

State & Federal Restrictions |

Q18 |

I live in Utah so termination guidelines are strictly mandated by the state government. |

Q19 |

[In] Texas, D&E has been significantly restricted, in that it may be performed only in an accredited hospital after 16 weeks. The political and social cultures have been an impediment to hospitals accepting termination of any type for any indication in our state/city. |

Q20 |

…terminations are not permissible in Federal institutions unless mother's life is in jeopardy. |

Institutional Culture |

Q21 |

Specifically, D&Es are obtainable during the week, but raise too many eyebrows on the weekends, so patients presenting on Fri p.m. often have IOL [induction of labor] just because of the calendar. |

Q22 |

The main problem at our institution is… a very conservative faculty- few [providers] would actually terminate pregnancies even when there is a lethal anomaly. |

Q23 |

Our involvement with pregnancy termination decreased remarkably when several members of our practice received death threats. |

Theme 4: Personal Issues |

Don’t like doing D&Es |

Q24 |

I'm not fond of doing D&Es, but believe that it is important for OBGYNs (including myself) to maintain skills so that the option can be offered to women with indications for second trimester abortion. I avoid doing them electively. |

Q25 |

I have practiced before and after Roe v Wade. I did abortions when no one else was available. I quit when others would do the procedure. I never liked abortions but dealt with too many septic abortions before Roe v. Wade. |

Religious beliefs |

Q26 |

I am well trained in termination by both induction and D&E but have stopped performing terminations for religious reasons. Because my partner has more ongoing experience with D&E, he performs most at our institution, but I perform them for some patients with fetal demise, especially when my partner is not available. |

Q27 |

Although I feel very strongly that the choice to terminate MUST be offered to patients, and that we as physicians have a moral obligation to do so, I do not perform termination services… my religion (non-Christian) respects the sacredness of life, so I choose not to provide termination services. |

Theme 5: Provider assumptions about patient preferences |

Q28 |

If terminating, I encourage patients to choose induction and to come to grips with their choice to terminate rather than try to emotionally side-step it with a D&E because I think it will be harder and longer dealing with it later. |

Q29 |

I often encourage labor induction so that the patient and family may see and hold the fetus, which helps with the grief process. |

Q30 |

I found it interesting in your questions about type of termination that you didn't consider induction to be a benefit over D&E for emotional reasons. I have seen MANY patients in my career who requested a termination and benefited significantly from seeing the baby after delivery, holding the baby, taking pictures, and spending time with the baby as it expired. D&E seems quick and "removed" but my experience tells me that patients more often regret not seeing their baby (even though a lethal condition) and "experiencing" the birth. Patients have expressed to me multiple times that they really appreciated experiencing the labor process and seeing their baby. Having even a few moments of life is very meaningful to them as they deal with a decision to terminate. Plus, there is also a benefit of autopsy and showing patients the specific birth defects that were seen on ultrasound. Even seeing their trisomy 13, 18 or 21 baby is helpful as they work through their loss. I have found in 17 years of practice that patients generally do "better" after an induction for a termination over D&E. |

Q31 |

I do not find that I need to bring up the issue of termination for people with fetuses with serious issues; if people wish one, they bring it up. Many of my patients appreciate this. |

Many respondents provide great depth regarding logistical barriers to offering D&Es (Theme 2). Two major subthemes emerged: (1) D&Es are often done by others and (2) insurance limitations affect patients’ and providers’ decisions. Respondents describe fragmented health care delivery systems (Q6-9). They characterize some compartmentalization of care as appropriate whereby agreements between institutions make providing abortion services more efficient or cost effective (Q7), while they characterize other divisions as arbitrary and frustrating (Q8, Q10). Either way, respondents worry that this compartmentalization of care places a burden on patients seeking abortion services. Respondents also describe insurance issues as a barrier in that insurance can influence both patients and institutions to favor one termination method. Interestingly, one respondent feels that patients generally prefer induction (Q12), but may be influenced to choose D&E when induction is not covered by insurance.

Many respondents highlight the challenges of providing abortions in an unsupportive environment (Theme 3), namely the difficulty working at religious and governmental institutions or in settings where the institutional culture is unreceptive to D&E provision. Many respondents discuss the limitations placed on their practice by differentiating between reasons for the termination (i.e., “elective” vs. “non-elective” or “indicated”) (Q17). State and federal laws are also cited as barriers with one respondent describing the state policy as an “impediment” to care (Q19).

Negative culture at the local level features prominently in the respondents’ comments. One respondent states that providing D&E on the weekends would “raise too many eyebrows” (Q21), suggesting a generally unsupportive culture, especially when regular staff is not present. Another respondent states that the culture of stigma is so dominant at his/her institution that “few providers would actually terminate even when there is a lethal anomaly” (Q22). Finally, concern for personal safety after death threats (Q23) is an extreme but pervasive example of the role of negative culture in dissuading physicians from providing abortions.

Many respondents voice personal opinions regarding D&E provision, with religion and personal aversion as prominent subthemes (Theme 4). Many describe a thoughtful approach to non-provision whereby they have chosen to not personally provide these services, but recognize the need for them and the centrality of patient choice. Many of these respondents seem to take solace in the fact that others will provide these services.

2021 Copyright OAT. All rights reserv

Lastly, some respondents describe a subjective feeling that induction termination is better for patients than D&E because it provides closure and helps with the grief process (Theme 5). One respondent states that this feeling consciously influences how she/he counsels patients (Q29). Echoing this notion, another respondent believes that choosing D&E is an attempt to “emotionally side-step” the consequences of abortion (Q28). These comments not only reflect provider assumptions about patient preferences, but underscore how assumptions may be translated into biased counseling regarding options for pregnancy termination.

Discussion

In our study, 69% of MFMs who provide D&E and 93% of MFMs who do not provide D&E report barriers to provision. D&E providers frequently report that negative culture such as religious, state and federal policies, and local stigma restrict their ability to provide abortion services. Provider harassment and antiabortion sentiment in the community are arguably the most important problem that abortion providers face[20]and recent studies suggest that this problem is worsening[8]. Stigma impacts providers in many ways, one of which is straining existing relationships with coworkers[21].One study found that abortion providers who have a professional community that normalizes abortion find their work more sustainable even when community-level stigma is intense[22]. Stigma surrounding abortion provision has been described as the “legitimacy paradox” wherein physicians doing abortions are depicted as illegitimate or deviant doctors. They become less likely to disclose their abortion work, which acts to further the social stereotype and alienate providers[23,24]. As a result, some providers may limit their practice to “non-elective” procedures in an attempt to achieve legitimacy. Similar to findings from a study that sharing experiences with other abortion providers is an effective stigma management tool, our qualitative findings indicate that many providers rely on support from coworkers to make their practice more sustainable in the face of stigma. Sharing workshops may be a valuable resource for all abortion providers, including MFMs who provide abortions[24].

Logistical issues are commonly reported, and providers experiencing them are more likely to work in an academic setting and with family planning fellows. Our qualitative findings suggest that some MFMs would like to be able to offer D&Es to their patients and spare them the burden of being referred to another provider; however, insurance-related barriers and difficulty with navigating complex health care delivery systems make it difficult for them to do so. FP subspecialists also report logistical barriers, and experiencing those barriers is associated with practicing in less restrictive regions, in a hospital-based practice, with lower D&E volume [14].Both FP subspecialists and MFMs incorporating D&E into their practice would benefit greatly from more streamlined systems for D&E provision, and those in academic, hospital-based settings may benefit the most. Logistical barriers may also be related to negative culture and stigma, and policy work addressing stigma may help alleviate logistical barriers.

Most MFMs who do not perform D&Es cite personal beliefs and lack of training as the reasons. Providing D&E is a personal decision, and although some MFMs choose to not provide D&E for personal reasons, many do not provide D&Es simply because they were never trained. Non-providers reporting lack of training as their main barrier provide more induction terminations than those who report other main barriers, indicating they are comfortable with second-trimester abortion. Some MFMs cite a relative lack of training in comparison to FP subspecialists as a reason for not doing D&Es. D&Es can safely be done by any physician with proper training and given the shortage of trained providers and the subsequent burden on women, any MFM who desires training should be encouraged. Nearly all MFM fellows believe that D&E training should be offered – and offered routinely – during MFM fellowship, but many fellowship sites do not offer training[25]. MFM fellows who receive D&E training have 7.5 times higher odds of intending to provide D&E after graduation[25]. Collaborative partnerships between MFM and FP fellowship programs would likely help to increase and optimize D&E training for MFM fellows.

Like all providers, our respondents have a myriad of personal beliefs regarding abortion. Despite deep-seated personal objections to providing these services themselves, many MFMsacknowledge the need for termination services. Consistent with ACOG recommendations for conscientious refusal, these non-providers reflect the professional obligation to provide patients with choices that are right for them[26]. However, some providers allow their personal beliefs to influence how they counsel patients, most often towards induction termination (Theme 5). Patient preferences cannot be elicited without skillful and unbiased counseling, and women’s preferences for abortion method are heavily based on their individual coping styles[27]. Grief resolution does not differ by abortion method[28]and D&E is the more common method.29 Women value the choice and identify their chosen method as a way to start the recovery process[27]. Women desire and deserve unbiased counseling regarding termination method.

Despite demonstrating that MFMs experience multiple barriers to providing D&E services, our study is not without limitations. Our results may not be generalizable to all MFMs given the modest response. In addition, responses may have been clustered by institution, which may have led to an over-representation of similar experiences. That said, respondent characteristics are similar to other published MFM surveys[30].

Given the national shortage of abortion providers, supporting MFMs in providing D&Es is a critical step towards improving patient-centered care for women. In two recent committee opinions, ACOG recently underscored the importance of working to increase access to abortion and training in abortion[31]. Our findings suggest that specific goals might include expanding training opportunities both during and after MFM fellowship, building networks and partnerships between D&E providers, and conducting training for affiliated personnel to decrease both negative culture and logistical barriers.

Authorship

Jennifer Kerns: Study design, data collection, data analysis, manuscript writing

Lauren Lederle: Data analysis, manuscript writing

Jema Turk: Data analysis, manuscript writing

Melissa Rosenstein: Study design, manuscript writing

Aaron Caughey: Study design, oversight of data collection, manuscript writing

Jody Steinauer: Senior oversight of all aspects of the study

Funding

L.I.L. was funded by the University of California, San Francisco Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI) Resident Research Grant. This publication was made possible in part by the Clinical and Translational Research Fellowship Program (CTRFP), a program of UCSF’s CTSI that is sponsored in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through UCSF-CTSI Grant Number TL1 TR000144 and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation (DDCF). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH, UCSF or the DDCF.

J.L.K. is supported by NIH/NICHD K23 Award no.1K23HD067222.

M.G.R. is supported by the NICHD, K12 HD001262.

Disclosure

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Jones RK, Jerman J (2014) Abortion incidence and service availability in the United States, 2011. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 46: 3-14. [Crossref]

- Lohr PA, Hayes JL, Gemzell-Danielsson K (2008) Surgical versus medical methods for second trimester induced abortion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev: CD006714. [Crossref]

- Hammond C (2009) Recent advances in second-trimester abortion: an evidence-based review. Am J Obstet Gynecol 200: 347-356. [Crossref]

- Kelly T, Suddes J, Howel D, Hewison J, Robson S (2010) Comparing medical versus surgical termination of pregnancy at 13-20 weeks of gestation: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG 117: 1512-1520. [Crossref]

- Autry AM, Hayes EC, Jacobson GF, Kirby RS (2002) A comparison of medical induction and dilation and evacuation for second-trimester abortion. Am J Obstet Gynecol 187: 393-397. [Crossref]

- Cowett AA, Golub RM, Grobman WA (2006) Cost-effectiveness of dilation and evacuation versus the induction of labor for second-trimester pregnancy termination. Am J Obstet Gynecol 194: 768-773. [Crossref]

- Bryant AG, Grimes DA, Garrett JM, Stuart GS (2011) Second-trimester abortion for fetal anomalies or fetal death: labor induction compared with dilation and evacuation. Obstet Gynecol 117: 788-792. [Crossref]

- Jones RK, Kooistra K (2011) Abortion incidence and access to services in the United States, 2008. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 43: 41-50. [Crossref]

- Jones RK, Zolna MR, Henshaw SK, Finer LB (2008) Abortion in the United States: incidence and access to services, 2005. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 40: 6-16. [Crossref]

- Eastwood KL, Kacmar JE, Steinauer J, Weitzen S, Boardman LA (2006) Abortion training in United States obstetrics and gynecology residency programs. Obstet Gynecol 108: 303-308. [Crossref]

- Foster DG, Jackson RA, Cosby K, Weitz TA, Darney PD, et al. (2008) Predictors of delay in each step leading to an abortion. Contraception 77: 289-293. [Crossref]

- Bartlett LA, Berg CJ, Shulman HB, Zane SB, Green CA, et al. (2004) Risk factors for legal induced abortion-related mortality in the United States. Obstet Gynecol 103: 729-737. [Crossref]

- Kerns JL, Steinauer JE, Rosenstein MG, Turk JK, Caughey AB, et al. (2012) Maternal-fetal medicine subspecialists' provision of second-trimester termination services. Am J Perinatol 29: 709-716. [Crossref]

- Turk JK, Steinauer JE, Landy U, Kerns JL (2013) Barriers to D&E practice among family planning subspecialists. Contraception 88: 561-567. [Crossref]

- Hoge R (1972) A Validated Intrinsic Religious Motivation Scale. J Sci Study Relig 11: 369.

- Aiyer AN, Ruiz G, Steinman A, Ho GY (1999) Influence of physician attitudes on willingness to perform abortion. Obstet Gynecol 93: 576-580. [Crossref]

- Glaser BG. Doing Grounded Theory: Issues & Discussion. United States: Sociology Pr; 1998.

- Tanaka K, Davidson L (2015) Meanings associated with the core component of clubhouse life: the work-ordered day. Psychiatr Q 86: 269-283. [Crossref]

- Glaser BG (2005) The Grounded Theory Perspective III: Theoretical Coding. Mill Valley, Calif: Sociology Pr.

- Henshaw SK (1995) Factors hindering access to abortion services. Fam Plann Perspect 27: 54-59,87. [Crossref]

- Freedman L, Landy U, Darney P, Steinauer J (2010) Obstacles to the integration of abortion into obstetrics and gynecology practice. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 42: 146-151. [Crossref]

- O'Donnell J, Weitz TA, Freedman LR (2011) Resistance and vulnerability to stigmatization in abortion work. Soc Sci Med 73: 1357-1364. [Crossref]

- Harris LH, Martin L, Debbink M, Hassinger J (2013) Physicians, abortion provision and the legitimacy paradox. Contraception 87: 11-16. [Crossref]

- Harris LH, Debbink M, Martin L, Hassinger J (2011) Dynamics of stigma in abortion work: findings from a pilot study of the Providers Share Workshop. Soc Sci Med 73: 1062-1070. [Crossref]

- Rosenstein MG, Turk JK, Caughey AB, Steinauer JE, Kerns JL (2014) Dilation and evacuation training in maternal-fetal medicine fellowships. Am J Obstet Gynecol 210: 569. [Crossref]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2007) ACOG Committee Opinion No. 385 November 2007: the limits of conscientious refusal in reproductive medicine. Obstet Gynecol 110: 1203-1208. [Crossref]

- Kerns J, Vanjani R, Freedman L, Meckstroth K, Drey EA, et al. (2012) Women's decision making regarding choice of second trimester termination method for pregnancy complications. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 116: 244-248. [Crossref]

- Burgoine GA, Van Kirk SD, Romm J, Edelman AB, Jacobson SL, et al. (2005) Comparison of perinatal grief after dilation and evacuation or labor induction in second trimester terminations for fetal anomalies. Am J Obstet Gynecol 192: 1928-1932. [Crossref]

- Kerns JL, Swanson M, Pena S, Wu D, Shaffer BL, et al. (2012) Characteristics of women who undergo second-trimester abortion in the setting of a fetal anomaly. Contraception 85: 63-68. [Crossref]

- Fox NS, Gelber SE, Kalish RB, Chasen ST (2008) Contemporary practice patterns and beliefs regarding tocolysis among u.s. Maternal-fetal medicine specialists. Obstet Gynecol 112: 42-47. [Crossref]

- Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women (2014) ACOG Committee Opinion No. 613: Increasing access to abortion. Obstet Gynecol 124: 1060-1065. [Crossref]