Abstract

Importance

Microbial keratitis is an increasing complication amongst contact lens wearers. In the absence of positive cultures, there should be a high index of suspicion for uncommon pathogens including acanthamoeba, herpes simplex, fungi and mycobacteria. Our unique case highlights mycobacteria as serious a pathogen which requires aggressive therapy. Successful treatment of mycobacteria could result in good visual potential.

Observations

We describe an original case of presumed Mycobacterium chelonae infection and management in an elderly contact lens wearer with a protracted clinical course of bilateral non-healing epithelial defects. The patient initially did not reveal she was a contact lens wearer. She later confessed to washing contact lens with domestic tap water, but later changed this practice by using a contact lens disinfecting solution. Inspection of her contact lens solution revealed expiry 3 years earlier, from which Mycobacterium chelonae was eventually isolated. Resolution of her keratitis only occured after triple antibiotic therapy of topical amikacin, moxifloxacin and azithromycin supported by oral clarithromycin. She later underwent penetrating keratoplasty in both eyes, with good visual outcome.

Conclusions and relevance

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of bilateral Mycobacterium chelonae keratitis arising from contaminated CL solution. This case illustrates the importance of considering Mycobacterium in the differential diagnoses when treating non healing keratitis. It is important to enquire about contact lens wear and hygiene in all keratitis cases, regardless of patient age. There is a need to create public awareness regarding the potential serious risk of CL wear and safe CL practice that includes monitoring by eye care professionals.

Introduction

Severe microbial keratitis can be accompanied by persistent epithelial defects, infiltrates and progressive corneal melt. The associated inflammation causes pain, tissue swelling and hypopyon. In the management of microbial keratitis, it can be challenging to detect and eradicate the causal pathogens. The treatment includes intensive topical agents that are toxic to the ocular surface while the use of systemic drugs can have significant side effects. We present a complex case of Mycobacterium chelonae infection in an elderly contact lens wearer with a protracted clinical course of bilateral non-healing epithelial defects, following poor contact lens hygiene.

Case report

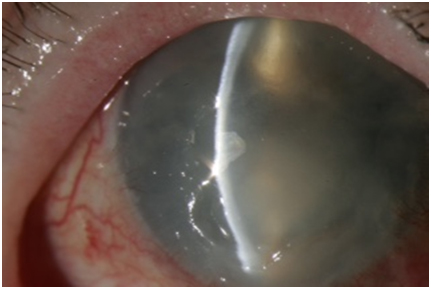

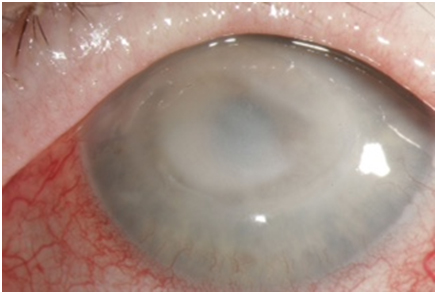

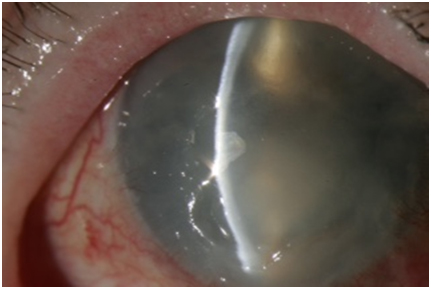

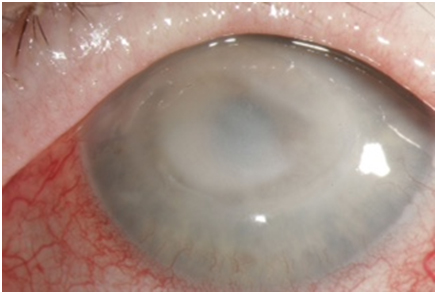

A healthy 75-year-old woman presented to our local ophthalmology department with discomfort in her right eye, associated with an epithelial defect (Figure 1). She had no previous ocular history, trauma, cold sore or shingles. The patient was initially treated for bacterial infection with ofloxacin drops. Oral acyclovir was commenced when a disciform epithelial defect developed. She was later treated with intensive cefuroxime, gentamicin, amikacin and moxifloxacin when her keratitis deteriorated with a hypopyon. Two months later, she developed a similar keratitis in her left eye, with subsequent scleral thinning (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Right corneal ulcer with epithelial defect

Figure 2. Left corneal ulcer with scleral thinning.

Herpes serology to HSV-1 was positive indicating previous exposure despite the fact that never had labial herpes. Blood tests [FBC, U&Es, LFTS, inflammatory markers (ESR and CRP)], including autoantibodies (ENA, ANA, rheumatoid factor and ANCA) were all normal. Multiple corneal scrapes, corneal biopsies and amniotic membrane transplant were all negative, which led to the assumption of a herpetic or fungal keratopathy with persistent epithelial defect due to impaired corneal sensation. Botox for protective ptosis was injected to allow her epithelial defects to heal.

The patient did not fit the profile of a contact lens wearer, and soft monthly lens use was only revealed upon detailed systematic enquiry. She professed initially washing her contact lenses with domestic tap water, but later changed this practice by using a lens disinfecting solution (Sauflon multipurpose solution) (Figure 3). However, inspection of her contact lens solution revealed expiry 3 years earlier.

Figure 3. Expired contact lens disinfecting solution.

Confocal microscopy confirmed multiple inflammatory cells and a few possible cystic lesions in both eyes. The above contact lens history and confocal microscopy findings suggested a high probability of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Active treatment against Acanthamoeba when instituted resulted in exacerbation of her keratitis.

The discovery of heavy contamination of her contact lens solution with Mycobacterium chelonae later led to the inclusion of antimicrobial agents against Mycobacterium as well as agents against Acanthamoeba.

The patient had several courses of intensive treatment followed by treatment to enhance healing of the epithelial defects. Despite being on prednisolone, oral clarithromycin, oral flubiprofen and the following topical medications in both eyes (azithromycin b.d., acetylcysteine 5% six times daily, brolene qds, chlorhexidine 0.02% five times daily, amphotericin 0.5% five times daily, moxifloxacin 8 times daily and lacrilube ointment at night), her keratitis failed to improve. There was progressive deterioration of corneal haze with scleritis bilaterally. Her visual acuity deteriorated to hand movements in the right eye and counting fingers vision in her left eye. Excessive inflammation caused pain and rapid destruction of ocular tissue which necessitated the titration of anti-inflammatory agents including corticosteroids to limit the effects. Eight months after ongoing intensive treatment, it was apparent that local investigations were not providing any clues as to the aetiology.

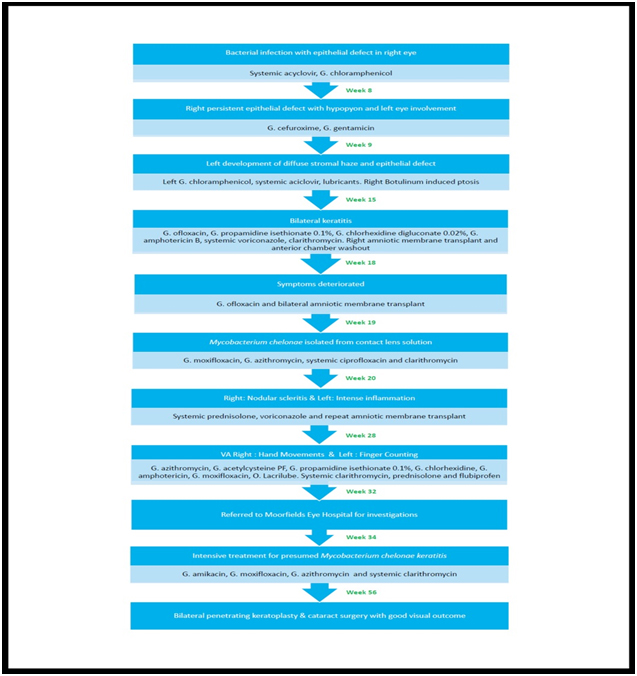

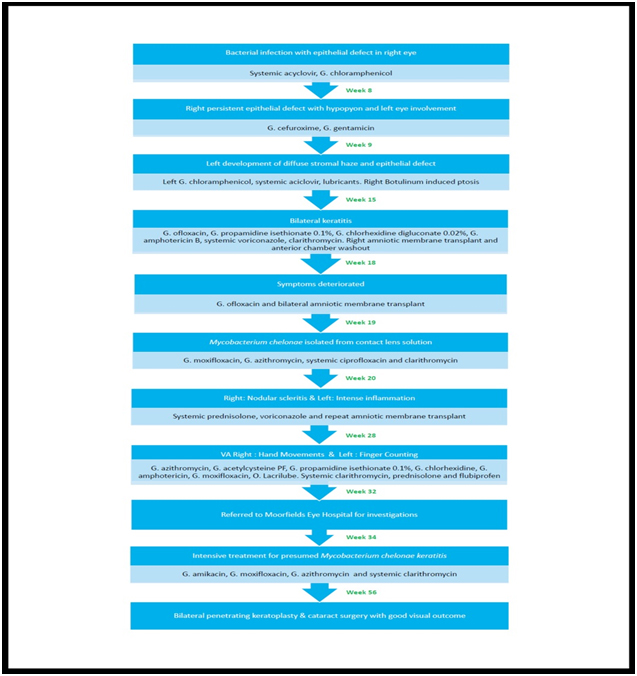

Moorfields eye hospital kindly helped to investigate this complex patient using their facilities and specialised laboratories for PCR. The outcomes of all the ocular microbiological investigations however were all negative: corneal and scleral biopsies, showed intense inflammation but no organisms. As the cornea had already been treated with intensive courses of agents against Acanthamoeba and Mycobacterium, the only conclusion left was that there must be resistant Mycobacterium present. Commencement of treatment with intensive topical amikacin, topical moxifloxacin and topical azithromycin and high dose oral clarithromycin, pleasingly led to resolution. The outcome was initially good following right corneal transplant but unfortunately there was right graft failure following rejection. The left visual acuity is currently 6/12 corrected following corneal transplantation and cataract surgery (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Summary of patient’s clinical sequelae and management.

Discussion

At presentation with a persistent epithelial defect, the patient was managed as hepertic keratopathy. The diagnosis of contact lens as a factor in her keratitis was not considered early in her presentation. Subsequently, only on direct interrogation did she admit to poor contact lens hygiene including swimming while wearing lenses, cleaning with tap water and a long expired cleaning solution. The discovery of Mycobacterium chelonae heavily contaminating the contact lens solution led to the inclusion of antimicrobial agents against Mycobacterium as well as agents against Acanthamoeba.

Mycobacterium chelonae, a saphrophyte found in air, soil and water, has been found to colonise antiseptic solutions and cause dacryocystits, canaliculitis, scleritis, and rarely endophthalmitis [1,2]. Surgical trauma (e.g. laser refractive surgery) or breakdown of the corneal epithelium increases the risk of surface infection. [3,4]. In our patient, the most likely source of bilateral keratitis was from cross contamination of her contact lens solution. The active ingredient in expired lens disinfectants may have become ineffective [5]. In such suboptimal environments, rapidly growing Mycobacteria are virulent enough to cause blindness by forming biofilms that affect antibiotic penetration and potential antimicrobial resistance [6].

Treatment of microbial keratitis has the “sterilisation phase” followed by the “healing phase”. Despite treatment to enhance healing of the epithelial defects, there was progressive deterioration of corneal haze with onset of scleritis bilaterally. Excessive inflammation and rapid destruction of ocular tissue required titration with corticosteroids.

Local investigations were inconclusive. The patient was referred to Professor John Dart at Moorfields Eye Hospital where all microbial investigations were negative. As the cornea had already been treated with intensive courses of agents against Acanthamoeba and Mycobacterium, the conclusion was that there must be a resistant strain of Mycobacterium. Resolution occurred only following intensive treatment with topical amikacin, moxifloxacin, azithromycin and systemic clarithromycin.

2021 Copyright OAT. All rights reserv

To our knowledge this is the first reported case of bilateral Mycobacterium chelonae keratitis arising from contaminated contact lens solution. This case illustrates the importance of considering Mycobacterium chelonae in the differential diagnoses when treating non healing keratitis. It is important to enquire about contact lens wear and hygiene in all keratitis cases, regardless of age. There is a need to create public awareness regarding the potential serious risk of contact lens wear and safe contact lens practice that includes monitoring by eye care professionals.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Professor John Dart and his team at Moorfields Eye Hospital for their help in managing our complex patient.

References

- Lim Bon Siong R, Felipe AF (2013) Nontuberculous mycobacterial infection after clear corneal phacoemulsification cataract surgery: a report of 13 cases. Cornea 32: 625-630. [Crossref]

- Feder RS, Rao RR, Lissner GS, Bryar PJ, Szatkowski M (2010) Atypical mycobacterial keratitis and canaliculitis in a patient with an indwelling SmartPLUG. Br J Ophthalmol 94: 383-384. [Crossref]

- Umapathy T, Singh R, Dua HS, Donald F (2005) Non-tuberculous mycobacteria related infectious crystalline keratopathy. Br J Ophthalmol 89: 1374-1375. [Crossref]

- Yamaguchi T, Bissen-Miyajima H, Hori-Komai Y, Matsumoto Y, Ebihara N, et al. (2011) Infectious keratitis outbreak after laser in situ keratomileusis at a single laser center in Japan. J Cataract Refract Surg 37: 894-900. [Crossref]

- Stapleton F, Carnt N (2012) Contact lens-related microbial keratitis: how have epidemiology and genetics helped us with pathogenesis and prophylaxis. Eye (Lond) 26: 185-193. [Crossref]

- Ortiz-Perez A, Martin-de-Hijas N, Alonso-Rodriguez N, Molina-Manso D, Fernandez-Roblas R, et al. (2011) Importance of antibiotic penetration in the antimicrobial resistance of biofilm formed by non-pigmented rapidly growing mycobacteria against amikacin, ciprofloxacin and clarithromycin. Enferm Infec Microbiol Clin 29: 79-84. [Crossref]