Abstract

The Adolescent Family: People Helping People Project is a dynamic community group intervention process to counteract social fragmentation and enhance resocialization in the Bahamas. This paper reviews three hundred and thirty four (334) group process sessions from September 2013 to March 2015 illustrating the pervasive negativity of shame manifested by loneliness, hurt, pain, anger, violence, family dysfunction, grief and loss. The majority of the Bahamian population is under thirty (30), making this intervention not only innovative but essential for the future development of the country.

Introduction

The Bahamas is an archipelagic nation situated between the coast of Florida and Cuba. It is a very young nation with 60% of its population under the age of thirty (30), and its two major industries are tourism and offshore banking. The primary Religion is Christianity and its population includes a majority of persons of African descent, and a minority of persons with loyalist-European heritage. Like many other countries in Caribbean and the inner cities of North America, the Bahamas is facing widespread social fragmentation as a result of a) the country wide cocaine epidemic in the 1980’s [1] and its continuing sequelae; and b) high unemployment rates especially among young people related to the recent international economic downturn [2]

The social fragmentation involves the formation of violent youth gangs associated with burgeoning rates of violent crime and murder, along with relationship dysfunction, domestic violence and child abuse. The average age of a murderer ranges from 16- 24 years old. This intervention for adolescents to enhance resocialization hits at the heart of the culture of violence and death in the country.

Description of the program

The Adolescent Family Group was developed as a key component in the Family: People Helping People Project. It is a dynamic, supportive, group process model in which adolescents share their story, undergo self-examination and reflection and experience transformation using the psychotherapy principles in the Contemplative Discovery Pathway Theory (CDPT) [3]. This theory posits that the individual develops through a series of selves. Starting with the natural self at birth, as a person experiences hurt and anger through their life, they experience the shame self involving abandonment, rejection and humiliation. Shame is so painful to the human psyche that the brain develops a shame false self involving self-absorption, self-gratification and control to block the fear of falling back into shame. The goal of CDPT is to reduce social fragmentation by liberating persons from being victims of the negativity of shame, to experience the positive feelings of love, gratitude and meaningful community in the process of resocialization [4].

In The Bahamas, the program is currently offered in nine (9) centers; boys and girls reform schools, an orphanage, program for teen mothers, junior and senior high schools and marginalized communities. Awarded a grant from the Templeton World Charity Foundation in 2013, the adolescent program has hosted over 800 sessions which are conducted by trained therapists assisted by trained Family Group Facilitators. After the completion of each group, a written report called a praxis is submitted which outlines the interactions, overt and covert themes and personal reflections by the therapist.

Thesis

In our experience shame is a powerful multifaceted emotion resulting from the shattering of dreams or expectations, leading to feelings of abandonment, rejection and humiliation [5]. In social fragmentation, a person becomes a victim of the negativity of shame giving them a negative view of the self, resulting in anger and disruptive community. On the other hand, resocialization involves the liberation from the negativity of shame to experience the positive emotions of self-acceptance, love and gratitude, creating constructive community.

We hypothesize that by analyzing the themes of the adolescent groups we would see the evidence of shame in society represented by anger, violence, addiction, loneliness, family disintegration etc. We also hypothesize that participation in The Adolescent Family program would lead to a decrease in negative emotions and destructive behaviors, resulting in positive emotions and constructive behavior.

Methodology

In this paper, we present a thematic analysis of the themes discussed in three hundred and thirty four (334) Adolescent Family Group Sessions since the start of the program in September 2013 until March 2015. As in the adult program, after each group session, the therapist or group facilitator writes a praxis report outlining the interaction between participants, the overt themes and covert themes discussed during the group process, along with a personal reflection.

Results

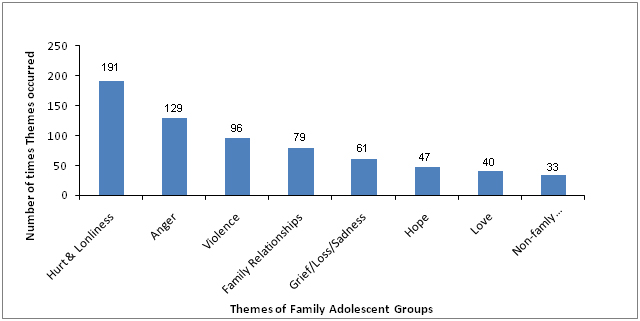

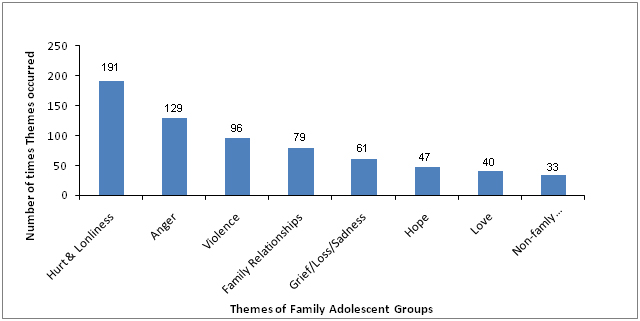

The thematic analysis reviewed a total of 334 praxis reports from nine (9) adolescent family groups yielding the following results: (1) Hurt/Pain/Loneliness (n= 191) (2) Anger (n= 129) (3) Violence (n= 96) (4) Family Relation-ships (n= 79) (5) Grief/Loss/Sadness (n=61) (6) Hope (n=47) (7) Love (n=40) and (8) non-family relationships (n=33) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Overt Themes of the Family Adolescent Groups

Discussion

In addition to the negative emotions expressed in the group, positive emotions such as hope and love also emerged. For example, a young lady claimed that when she entered the Family group, she was angry and very unhappy. After three years participating in the group, she developed a positive outlook on her life and family and became more hopeful about her future. Now in college, she is thankful for the experience of the group where she was able to release her hurt and anger and experience hope. Many of the adolescents experienced the trauma of shame associated with abandonment, rejection and humiliation manifested by repressed anger, violence and communication.

Hurt and loneliness

Adolescent participants referred to the program experienced a variety of behavioral, social and emotional problems. The role of the Adolescent Group is to address the underlying feelings leading to negative behavior. In our experience, adolescents suffer from a form of alexithymia, moving from thought to action while ignoring the underlying feelings. This lack of ability to process their feelings makes it difficult for them to act appropriately and encourages social fragmentation. In the program, a number of adolescents learned to express their feelings and became more adept in interpersonal relationships.

Case vignette

During one of the sessions at a Reform School, a participant was overwhelmed by the session but refused to admit it. Eventually, with much support, she expressed that the discussion evoked traumatic memories of her mother’s funeral in which she observed the coffin being lowered into the grave. She said that she was envious of other group members whose mothers were still alive and able to talk with them. Her mother was her best friend and the loss of her was extremely painful. Now she feels a deep sadness and loneliness. The group was touched by her story and did their best to support her.

Anger

“I am angry" is a common expression of Bahamian adolescents. Although a normal and healthy emotion, anger is used as a defense mechanism to protect them from dealing with other painful feelings. In our program, many of the participants use anger to justify their actions instead of exploring the underlying range of emotions. They say ‘if you shame me, I get angry, if you hurt me, I get angry, if you disrespect me, I get angry’. Social fragmentation in the country is characterized by the inability to express a range of deep, negative emotions, thus encouraging communication through violence and self destructive behavior.

Case vignette

While discussing the issue of friendship, some persons became visibly upset because they felt betrayed in the group. Their anger escalated and an argument ensued. Before the facilitators could intervene, two participants became involved in an aggressive altercation, punching and pushing each other. Eventually they were separated and shouted disrespectful comments at each other. The group was terribly upset, expressing harsh words and the threatening violent behavior.

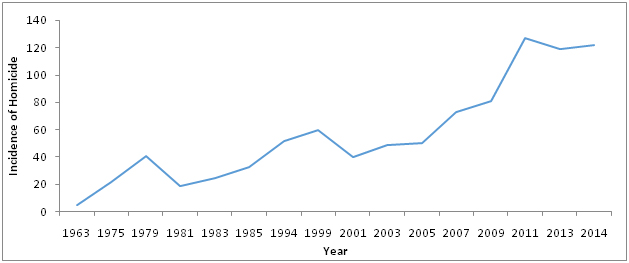

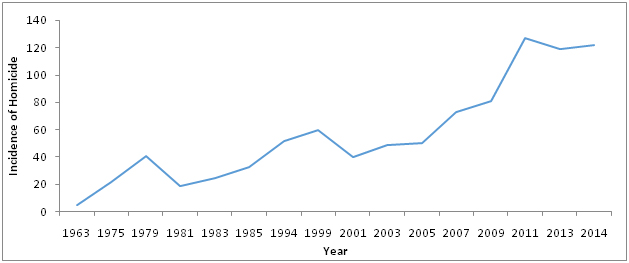

This behavior is learned and is characteristic of the larger society evidenced by the burgeoning rates of violent crime (Figure 2). As described in the vignette, the anger rises quickly and erupts into destructive confrontation. The goal of the group process is to produce effective conflict resolution by helping the adolescents to express their negative feelings to prevent verbal confrontation and violence. This is a long-term process requiring patience, understanding and determination.

Figure 2. Incidence of Homicide in the Bahamas (1963-2014)

Violence

When an adolescent has been shamed, according to CDPT, the shame false self defends the person from the shame process of abandonment, rejection and humiliation. However, when confronted by continuing hurt and anger, the shame false self is unable to defend against the murderous rage which projects the person into a destructive spiral called the Evil Violence Tunnel. In this tunnel, their identity is challenged by physiological arousal, diminished intelligence and decreased ability to make moral choices in their best interest. Eventually, the shame rage acts out against the self producing self-harm (or suicide) or is projected onto others, producing violent behavior, even homicide.

Case vignette

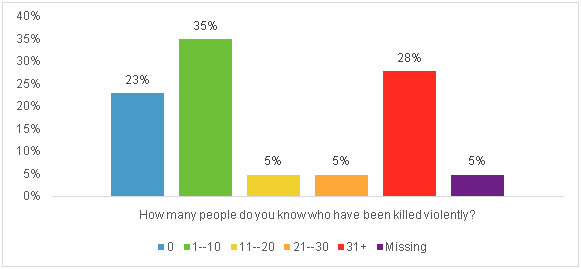

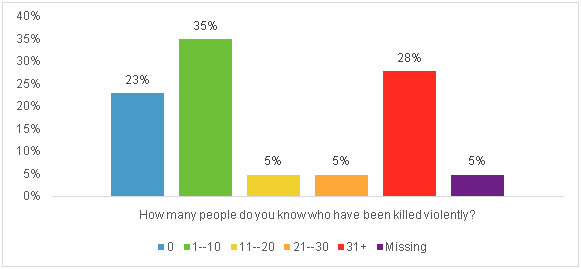

A young man was referred to the group because of fighting at school and being distant at home. Initially in the group, he was distracted, unengaged and resistant. Asked to share why he was in the program, he responded that it was because he was violent. He went on to share a gruesome story which deeply affected the group. He said one night his parents began to argue. His father assaulted his mother and he got between them. Becoming enraged, his father stabbed him four times to get him out of the way. The father then went on to kill the mother by stabbing her repeatedly. As he shared this painful story, he was visibly shaken and still in shock. Group members were stunned by the cruelty of the story. Remaining silent, they found it difficult to respond. This experience weighed heavily on the group, reminding them of the violence in the wider society. The good news is the young man continues in the group, working through his pain and difficult situation. The group has strongly supported him and he has reciprocated by expressing his appreciation of them being there for him. He completed high school and currently attends college. This story reflects the deep hurt and conflict experienced by many adolescents. Quantitative analysis of the adolescent family groups reveals that 79% of adolescent participants knew at least one person who had been killed violently (Figure 3). These results explain why adolescents act out in violently, seeking to cope with the tragic stories of their lives.

Figure 3.

Figure 3. According to quantitative analysis carried out on the Adolescent Family program in April 2015, more than 70% of participants admitted they knew at least one person who was violently killed

Family relationships

CDPT, based on the dynamics of shame, encourages persons to move beyond the blame process and accept their part of the responsibility for whatever problems they have because “if I am my problem, I am my solution”. In the adult population there is a clear understanding of separation of self and family. However in the adolescent population, separation-individuation is not complete because the adolescent is still in the process of identity formation. As a result, the adolescent seeks to assert their new-found independence within the family. In the Family group process model, the same dynamics occur, where the adolescent seeks to assert themselves. Paradoxically, adolescents crave intimacy but still seek distance. Creating confusion for them, they are hurt most by people who care for them. Being vulnerable, they are sensitive to rejection of love which may become a catalyst for violence. Hurt love presents itself as anger, resentment, bitterness and hardness of the heart [3]. All these elements may be observed in the group process and the facilitator has to skillfully deal with them while creating a safe holding environment for the adolescent to experience the separation-individuation process.

Case vignette

During the course of one of the groups, a young lady shared about the development of the poor relationship with her mother after she married her step- father. She was angry because her mother put her new husband first in everything, showing him more affection and spending more time with him. According to her, she and her brother became second class citizens in the home. She only speaks to her step-father during the provision of the meal, otherwise, there is no conversation between them. Deeply hurt, she has shared her unhappiness with her mother repeatedly, but there is no change. Upon hearing this, a number of persons in the group from marginalized families, shared how they also had great difficulty dealing with their step-parents and estrangement from their biological parents. A very sensitive topic in the group, we find that adolescents only become assertive in the home if we listen effectively to their underlying hurt and shame. Adolescents, although resistant, seek love from their family and are deeply shamed when it is not received.

Grief/loss/sadness

Grief and loss are constant themes in the Adolescent Family Groups. According to CDPT, life is wounded and grief is a necessary part of living. We have to make the transition between letting go of what used to be, and accept things as they are. However, it is difficult to let go because our identity is connected in past experiences. This is particularly challenging for adolescents whose identity is poorly formed and loosely held together.

In The Family program, grief and loss are usually characterized by rebellion and aggression as the adolescent creates distance between the life before the loss of the person, and adapting to the new reality of life. As a result, the individual is vulnerable and craves understanding and love.

Case vignette

During an adolescent female group, each girl was asked to look into a mirror and share what they saw. One girl whose mood was very sad, said, “I hate what I see”. As the room grew silent, she went on to say that the only reflection she saw in the mirror was that of her father (who passed away recently). This loss was devastating, leaving her feeling alone, angry and afraid. In her own words, she asked, ‘What will become of me? Will I be able to make it without my father?”

The young lady was obviously grieving deeply and in some way, her identity was lost in the grief. But as the group sessions continued, she was able to work through her painful feelings of loss and came to a deeper acceptance of herself with a more positive outlook. Grief is very threatening to adolescents whose identity is extremely fragile.

Hope

Victor Frankel shared that “when we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves” [6]. This statement summarizes the process of the group and is the goal in helping adolescents work through their pain and shame.

Analysis of the themes reflect that prior to attending to the group, many adolescents had a negative attitude towards their life and future. After participation in the group, they developed a more positive outlook and a better sense of well-being, expressed in a decrease in social fragmentation and destructive activities.

Case vignette

Even after leaving The Family, hope continues. Five years ago an angry young woman was introduced to the group. Admitting that she was forced to attend by her mother, she had no interest in being there. During the group, she sat quietly, and when she did speak, it was to express hatred towards her mother. As time progressed, she admitted that she did not feel beautiful because of her athletic build. She was angry at her mother’s authoritative attitude. She was bullied and had few friends. Initially she tried to cover her social isolation with periodic angry outbursts. As she continued to attend the group, she felt supported and experienced love and acceptance by the participants. She learned to share her painful feelings without shame of her appearance, and was also able to ask the group for help. As a result, she became more positive in her outlook, better behaved at home and more accepting of her mother. The good news is that she was able to graduate from high school and is currently in college. According to her, she and her mother have a wonderful relationship built on love and mutual respect.

This example demonstrates that even if a person feels negative about themselves, receiving acceptance and love in the group allows them to share their negative feelings and experiences, which ultimately brings meaning and hope to their lives.

Love

The concept of shifting from shame to love is a major theme of the adolescent group. Group members are taught to change their perception of the world by working through their shame and hurt by sharing their authentic stories in a loving and non-judgmental environment. In so doing, they release their pain and make space for love, which is evidenced by their demonstration of positive attitudes and constructive behavior.

Case vignette

One of the groups in the marginalized community focused on a member who was particularly disturbed by how he had been treated that week. Rejected by his peers, and his parents, he felt very angry and sad. After eight weeks in the group, he was able to share his isolation and painful experiences with others. He shared that since his mother married his step-father, he has felt unloved because of being deprived of using the phone, cable or Internet. At school, he was rejected by his peers and felt worthless and humiliated. As he talked, he paused and pretended to use a cell phone. When group members questioned him about this, he said that he had few opportunities to socialize with others in a healthy environment. The group members immediately questioned why he wanted a cell phone if it was hard for him to connect with others. He explained that he thought people would not know it was him on the other end of the phone and he would be connected to them. The group remained silent and the facilitators reminded him that “The family” was a safe place where he could engage others and receive support. One of the more aggressive group members reminded everyone that the empathy we show others is often returned to us. He eventually felt supported by the group and tearfully admitted that this was the first place he felt loved by others.

Adolescents have many doubts and often judge themselves as being unloved or rejected. However, in a loving environment where they are accepted, these doubts are neutralized and they are able to work through their feelings of shame, particularly as they relate to anger and fear. In so doing, they make the perceptual shift from shame to open their hearts to love and be loved.

Interpersonal relationships (non family relationships)

This particular theme is prevalent, especially in discussions where participants detail their interactions with peers. Interpersonal relationships are dynamic systems that change continuously during an adolescent’s life. On the positive side, these relationships have a rapport that includes empathy, trust, honesty and accountability. Negative interpersonal relationships however are often characterized by avoidance, superficial connection, lack of compatibility, lack of commitment to make things better, lack of forgiveness and lack of boundaries. Healthy, positive interpersonal relationships are critical to the adolescent’s emotional and social development and feelings of support. As the old Bahamian proverb says, “It is easy to break one stick, but it is hard to break ten”.

Case vignette

A young man from one of the groups complained that a fellow student bullied him repeatedly. Pleading with the bully to leave him alone, he complained to the teachers, but no one came to his aid. Eventually unable to take it any longer, he punched and pushed the perpetrator, causing him to fall from a two-story building, breaking a leg and an arm. This mild-mannered young man had become trapped in the Evil Violence Destructive Tunnel and found himself acting destructively. In the group, he was honest in sharing about what happened and felt relieved when some members of the group empathized with his plight, because he was being continually bullied. As a result, the young man became an active participant in the group and developed meaningful interpersonal relationships. This growth eventually spread to his life outside the group.

CDPT encourages self-reflection and introspection on the path to discovery, encouraging adolescents to accept themselves and refrain from blaming others for their problems. In the group, as adolescents share and help each other, they bond together, developing meaningful relationships associated with positive attitudes and behavior.

Conclusion

This thematic analysis concludes that the most prevalent emotions members of the adolescent Family group are facing are pain, hurt and loneliness. These are the faces of shame representing profound community and social fragmentation. As adolescents progress in the Family group, they learn to share their stories, expressing their pain and hurt thereby reducing their shame and becoming more open to positive attitudes and behaviors which are the hallmark of resocialization. In the shame process, persons tend to deny their problems, judge and blame others causing further isolation, negative feelings and behaviors. According to CDPT, as adolescents grow and heal through the sharing of their painful stories, they become more hopeful and solution-oriented when presented with daily stressors or circumstances. This proves the efficacy of the Contemplative Discovery Pathway Theory (CDPT) and the dynamic group process model as a successful intervention for resocialization.

Acknowledgements

This project is funded by the Templeton World Charity Foundation.

References

- Jekel JF, Allen DF, Podlewski H, Clarke N, Dean-Patterson S, et al. (1986) Epidemic free-base cocaine abuse. Case study from the Bahamas. Lancet 59-462. [Crossref]

- Allen DF (2013) Report on Crime.

- Allen DF, Mayo M, Allen-Carroll M, Manganello JA, Allen VS, et al. (2014) Cultivating Gratitude: Contemplative Discovery Pathway Theory Applied to Group Therapy in the Bahamas. J Trauma Treat

- Bethell K, Allen DF, Allen-Carroll M (2015) Using a Supportive Community Group Process to Cope with the Trauma of Social Fragmentation and Promote Re-Socialization in the Bahamas. Emergency Med Open Access.

- Allen DF (2010) Shame: The Human Nemesis. Washington, D.C. : Eleuthera Publications.

- Frankl VE (1946) Man's Search for Meaning. Vienna.

Figure 3. According to quantitative analysis carried out on the Adolescent Family program in April 2015, more than 70% of participants admitted they knew at least one person who was violently killed

Figure 3. According to quantitative analysis carried out on the Adolescent Family program in April 2015, more than 70% of participants admitted they knew at least one person who was violently killed