Abstract

Background:Placing the woman at the centre of midwifery care is a key recommendation for optimising Dutch midwifery care, although not fully utilised.

Methods:Semi-structured interviews with ten Dutch midwives. The interviews were analysed using the Attitude, Social influence & self-Efficacy (ASE) model.

Results:The research identified the following themes: Woman-centered care manifested in providing information, assessing needs, taking time, articulating a vision about woman-centered care and adhering to a physiological approach of pregnancy and birth and to care standards. Woman-centered care was perceived as care that is adapted to women’s needs but it was not regarded as infinite. Midwives’ overall intention and attitude about woman-centered care was positive, although midwives often could not fulfil these intentions as a result of perceived barriers. Midwives’ personal boundaries, women’s unrealistic wishes and logistic factors, such as time were barriers to provide woman-centered care. Personal factors, such as midwives’ personal outlook on life, influenced woman-centered care. Woman-centeredness was also influenced by the woman’s expression of her individual wishes or by the woman-centered care norm of colleague midwives. Not all midwives perceived that they had the abilities to provide woman-centered care. Being familiar with one’s population and with woman-centered care were perceived as helpful. Midwives associated vocational characteristics with woman-centered care.

Discussion/Conclusion:Woman-centered care behaviour is determined by various factors, predominantly showing a paradox between behaviour and attitude and intention. Woman-centered care therefore needs a philosophical underpinning to provide guidance for midwives.

Keywords

woman-centered care, midwives, perceptions, attitude, social influence, self-efficacy

Introduction

Dutch maternity care includes midwife-led care and obstetric-led care. Midwives based in the community setting provide midwife-led care to women with uncomplicated pregnancies, including homebirth [1]. When obstetric or medical complications arise, women are referred to clinical obstetric settings [1]. Two-thirds of Dutch midwives provide care as self-employed independent practitioners and a third work in clinical obstetric settings under the auspices of an obstetrician and are employed by the hospital [2].

Most of the primary care midwives (81%) work in cooperation with other midwives in practices with 3 or more midwives. Nineteen percent work in small-sized practices with 1 or 2 midwives [2]. Dutch midwives provide antenatal care including health education and risk selection, intrapartum and postpartum care [3,4]. On average the annual caseload of the midwife is 110 women. About eighty percent of women in the Netherlands start their care in midwife-led care [5]. Therefore, Dutch midwives play a central role in women’s pregnancy and childbirth process.

Mother and child at the centre of midwifery care

As a result of the EURO-PERISTAT project that revealed relative high rates of perinatal mortality and morbidity and substandard care practices in the Netherlands [6,7], Dutch midwifery care has been under close scrutiny of the Health Care Inspectorate.

In response to these governmental concerns, the Dutch Steering Committee for pregnancy and birth drew up their report ‘A good start’, including seven designated key points with according recommendations in order to optimise care for mothers and their (unborn) children. The first and main key point included: mother and the (unborn) child at the centre of midwifery care [8]. Since the publication of the report, there has been emphasis on improvement of coordination and cooperation of perinatal care and improvement and monitoring of perinatal health outcomes. Initiatives with regard to public health, addressing specific groups such as asylum seekers and women with psychiatric disorders were prompted by the recommendations. However, a systematic evaluation of the changes and initiatives in Dutch perinatal care established that, in contrast to the key recommendations, the Steering’s Committee key point mother and child at the centre of care, has been insufficiently addressed [9]; a key point that is strongly associated with woman-centered care [10]. Dutch midwifery care lacks a position statement, code of ethics or guidelines about woman-centered care [4].

Woman-centered care

Underpinning its importance in midwifery care, several studies showed that woman-centered care is associated with reduced likelihood of interventions as well as increased maternal satisfaction with care and childbirth experiences [11-15]. Woman-centered care is described as the behaviour of an individual midwife whopromotes an environment of shared power and responsibility between a woman and her midwife, in which woman-midwife connectedness and an interpersonal relationship are key elements [11,16]. According to midwifery ideology, woman-centerednessis perceived as a core premise of the midwifery profession and as the (moral) right thing to do [17]. Although the term woman-centered care has been frequently used, review of the literature shows that interpretations of the term in general differ and there is no consensus about its meaning and its use in midwifery [18-22].

Since the midwife is the main care provider during pregnancy and childbirth, this suggests she has a key role in utilising woman-centered care. It is therefore essential to explore the subjective experiences of midwives about woman-centered care. Midwives’ individual behavioural beliefs, normative beliefs, control beliefs and their intent are the corresponding antecedents and the underlying structure of midwives’ woman-centered care behaviour[23]. Therefore we were specifically interested in the perception of midwives about the underlying factors of woman-centered care.The purpose of this study was to obtain self-referent perspectives of influencing factors of woman-centered care of Dutch midwives.

Methods

Design

This exploratory study utilized a qualitative design with semi-structured interviews as the data-collection method. We used an ethnographic approach to map midwives’ perspectives and their subsequent behaviour with the underlying causes and implicit rules [24]. Data are collected from persons whose interests are given voice with a rich description of human experience in a cultural context [25], aiming to generate knowledge about invisible, interconnected, taken-for-granted forms of practice that rule everyday life [26]. During the interviews we used self-referent perspectives and narratives in order to process thoughts about one’s self or about personal experiences [27,28].

Participants and setting

Qualified midwives working in all Dutch midwifery care settings were eligible for the study. There were no exclusion criteria because we aimed to include subjective perceptions that were heterogeneous in content [29]. We aimed to recruit midwives from various regions and working in various care settings, from various-sized midwifery practices and teams, in order toinclude a variety of perspectives.

Our sample included ten midwives who were between 28 and 54 years of age with three to 27 years of work experience. The midwives in primary care practised in rural and urban settings and were situated in the central and southern regions of the Netherlands. Two midwives practised as a locum midwife, while the other midwives were either self-employed and practice owners or were employed by midwifery practices. Two midwives working in the clinical settings were employed by semi-rural and urban hospitals situated in the Western and central regions of the Netherlands. The team sizes varied between two to 19 midwives. One midwife had previous practice experience in Africa. All, but one midwife, were educated in the Netherlands. One midwife was educated in the United Kingdom.

Procedure

To recruit eligible midwives for our study we used maximum variation sampling, including purposive sampling as well as the snowball sampling technique to explore perspectives of woman-centered care across varied cases of midwives [30]. Midwifery practices and obstetric units in the Netherlands have websites to inform (potential) pregnant women about their practice, often including their vision statements with regard to woman-centered care. We selected 19 midwifery practices from the 223 midwifery practices and obstetric units that offer placements for the students of the Faculty of Midwifery Education & Studies, Rotterdam that voiced their vision about woman-centered care on their website. We approached these practices by telephone to inform them about the study and to explain the purpose of the study. All the midwives verbally agreed to receive additional written information about the context and scope of the study. Eight midwives agreed to participate. These midwives were asked if they knew colleagues in their professional or personal network with different or opposed meanings and perceptions about woman-centered care than the interviewee or who had different backgrounds in term of for instance education institution, practice-size and years of work-experience. Two other midwives were approached who also agreed to participate. In total ten midwives consented to be interviewed. The reasons for non-participating were due to lack of time, being on-call or not able to find a suitable interview date for the participant and researchers. None of the participating midwives worked together in the same practice or team at the time of the interviews. Two researchers, (AB, CS), conducted the interviews and were unfamiliar with the participants prior to the interviews. They performed two pilot-interviews to increase reliability and internal consistency of the usage of the interview protocol and topic list [31]. The researchers had conducted a literature review about woman-centered care and had reflected on their own ideas and thoughts about woman-centered care. As they had little experience with elements of woman-centered care, their own perceptions were experienced as theoretical and were not believed to influence participants’ answers. Additionally, the researchers regarded their status as student-midwives as non-threatening for the participants.

The interviews were scheduled between 27 April and 11 May 2015 at a time and place convenient for the participants, which in all cases was the midwife’s workplace, and lasted between 35 to 60 minutes. Participants were informed that there were no wrong answers and they were encouraged to reveal anything they wanted to say about the topics addressed in the interview. The participants were assured of confidentiality and anonymity. Both researchers (AB, CS) were present at the interview, where one researcher conducted the interview and the other researcher observed and noted non-verbal communication of the interviewee and checked if all topics were addressed. Consent for audiotaping was obtained prior to the interview.

Interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. Field notes of non-verbal communication were added to the transcripts. Each interview was transcribed and returned to participants for a member check, giving them an opportunity, should they wish, to change or remove any data [25,31]. All participants agreed with the transcripts and no data were removed.After this member check the transcripts were anonymized, we deleted the audiotaped interviews and we stored the transcripts in a password-secured computer.

The Research Ethics Committee of Erasmus MC confirmed that because of the noninvasive character of the study ethical approval was not required, and advised to conform to the ethical principles of the Central Committee on Research Involving Human Subject (CCMO) [32]. All participants freely consented to join the study.

Measurement

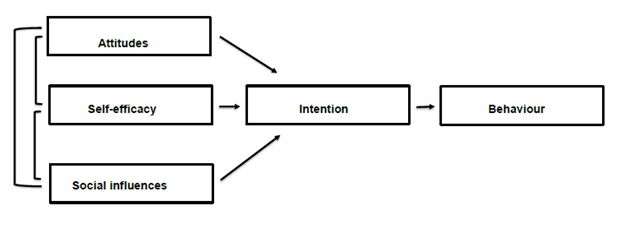

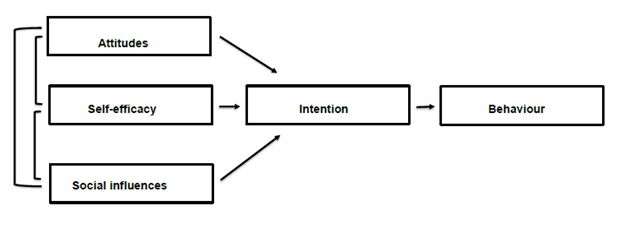

We used a prioria semi-structured topic list for our interviews based on the Attitude–Social influence–self-Efficacy(ASE) model (Figure 1). We chose this model to structure the data collection and analysis processes of self-referent perspectives about midwives’ underlying factors of woman-centered behaviour and to increase methodological rigour, theoretical connection and heuristic relevance[33,34]. According to the ASE model, behaviour can be explained by behavioural intention, which in turn is determined by Attitude(the degree to which an individual has a (un)favourable evaluation of the behavior in question), Social influences (perceived expectations of others, social norm and social pressure and support), and perceived self-Efficacy(perceived ease or confidence (or difficulty) an individual has for performing the desired behavior). Intention, also a determinant of the ASE model, precedes behaviour and describes the willingness to perform certain behaviour such as providing woman-centered care. The ASE model is widely used to explain professional behaviour, including midwives’ behaviour[35].

Figure 1. Attitude-social influence-self-efficacy model.

Analysis

We used thematic analysis [31] of incorporated transcripts and field notes. As a reliability check the transcripts were read, reread, and marked independently by the second and third author (AB, CS) to achieve a sense of the whole, to assess the findings and to identify the content of the ASE constructs. This also enhanced the credibility of the coding and the content of the different constructs [25]. The two researchers used a coding tree and compared the results and they resolved differences through discussion till they reached consensus. Quotes were then labeled using constructs of the ASE model [35,36]. During the analysis process,several external determinants barriers, supporting factors, midwives’ characteristicsandpersonal factors, not covered by the ASE model, were identified. The research team interpreted the text, discussed it, and mutually agreed on the identified ASE themes and framed the additional themes to the ASE model to get a comprehensive understanding of the meaning of the findings.

Findings

ASE themes

Behaviour

Midwives described their woman-centered care behaviour as providing information and unstructured assessment of the woman about her needs and wishes. Midwives asked questions based on issues induced discussion of routine topics or as a result of issues that spontaneously come up during booking or other moments of contact, like antenatal or postnatal appointments. Taking time to talk with a woman and evaluation of care were also mentioned as woman-centered care behaviour as well as providing continuity of care and carer. Some midwives adhered to the physiological approach of pregnancy and birth as guidance for providing woman-centered care. Other midwives described that providing care according to protocols and guidelines or providing supply-driven care is their way of providing woman-centered care as they believe this guarantees quality of care.

“I do support the fact that we [midwives] need to consider the woman and her wishes etcetera etcetera… but really, you need protocols and guidelines to, uh, deliver good standards of care, benefitting the woman (…) … and her needs… isn’t it?”

Based on positive experiences of women, some midwives articulated their positive opinion and vision about woman-centered care in public, like for instance on their practice website, as a positive method to attract women to their practice.

“Woman-centered care results in satisfied women so I tell women I think it [woman-centered care] is important (…) when they [women] tell this [that the practice provides woman-centered care] to other women, these women are more likely to sign up with us [practice].”

Intention

Although, in general the midwives stated that they were willing to provide woman-centered care, they always immediately followed their behavioural intentions with perceived barriers that withheld them to fulfill these intentions.

“I do want to provide woman-centered care but it is often not possible because, well… not that I don’t want to BUT … for instance lack of time or just being too busy.”

Attitude

In general midwives viewed woman-centered care as where the woman is at the centre of care, tailoring care to meet the woman’s needs. Midwives perceived woman-centered care as important and positive. Some midwives considered it as being the essence of midwifery practice but also considered woman-centeredness as a logical attribute of ‘caring for others’. Several midwives perceived woman-centered care as a complicated concept. Only a few midwives expressed that the woman should be the leader of her own care but most midwives thought that this is not very practical.

“It is a good thing… important … positive … you know, women should be informed… they should have choices, and uh, make their choices without experiencing resistance and, well … you know … all of that (…) that there is more attention for women’s wishes … who she is and so on … it’s you know, part of working with people, but … uh, to make her the leader of her own care … nah, that’s not workable.”

Most midwives perceived woman-centered care as the ideal way of providing midwifery care but also experienced it as a new trend in midwifery care. Most midwives regarded this as a positive development in care, but others perceived it as a temporary trend in care.

“… a feeling of a bit of a hype so to speak… like I just said, woman-centered care is hot and popular and it becomes more (…) well a bit of a loose end or something like that. Sometimes I wonder … uh, to what extent woman-centered care still has a true meaning and value.”

Most midwives experienced that there were limits and boundaries to woman-centered care. It wasn’t regarded as inexhaustible or absolute. Boundaries seemed to be linked to barriers and personal factors.

“Sure, uh, you listen to the woman’s wishes … within limits, because I personally do think that, uh, there are limits to what extent you meet her [the woman] wishes.”

Social influences

Midwives regarded that the expectations of women predominantly influenced their woman-centered care; they experienced that some women expect that ‘ the midwife knows best’ while other women expect personal attention and the possibility to talk about their wishes and expectations. Midwives perceived that in particular assertive women in their practices direct their woman-centered care provision.

“I think that they [women] nowadays request it [woman-centered care]. That they [women] demand things (…) it seems that the more woman-centered I work, the more and the bigger the demands get. The less tolerance.”

In general midwives did not notice any expectations from their colleagues with regard to woman-centered care, unless woman-centered care was the norm in a practice. When midwives in a team share the same view and norm about woman-centered care, midwives experienced social support from their colleagues in providing woman-centered care. They experienced this as a feeling of mutual understanding, which connects them. On the other hand, when a midwife was the only team member who conveyed a positive view or attitude on woman-centered care or the wish to provide woman-centered care, midwives perceived social pressure from their colleagues.

“That [perceived social support or pressure] varies per practice and per colleague but, uh, I feel that some practices allow it [woman-centered care] and some not, that is obvious.”

Self-efficacy

Midwives expressed different thoughts about being capable to provide woman-centered

care. Some were confident about being able to provide woman-centered care, others were more doubtful if they were able to provide woman-centered care or whether they had enough skills, and some didn’t know if they were able because they didn’t know what exactly they needed to do. The lack of knowledge about woman-centered care and the lack of an ethical code and guidance seemed to affect self-efficacy.

“See, well … when you tell me this and that is what you need to do, I think okay that is what I need to do … I think okay, on this list I do six of the ten things that I should do … but I don’t know do I … you know, maybe I am not as woman-centered as I think I am, or maybe I am, but I don’t know (…) what is it [woman-centered care] exactly? (…) where can I found the information, who tells me?”

Barriers

Midwives perceived various barriers that prevented or hindered woman-centered care provision and they distinguished between intrinsic and extrinsic barriers. An intrinsic barrier that was mentioned by most of the midwives was the lack of an emotional connection or sense of a positive relationship between the midwife and the woman. Midwives felt that this complicated the assessment of a woman’s needs. Instead, they need a woman to self-disclose. A lack or limited information may result in incorrect interpretation of a woman’s needs and hinders woman-centered care provision.

“Sometimes it [connection] is just not there, but … if she doesn’t tell me, how I know (…) do I give her what she needs … I don’t know.”

In addition, several midwives perceived their own personal boundaries as the main barrier for woman-centered care. These boundaries could have professional, safety, economical and personal reasons, while having a personal meaning and value. The intrinsic barriers seemed to influence midwives' attitudes and were strongly connected to their self-referred behaviour.

“I think that if I think that it [unlimited support of women’s wishes] is not necessary… so … well … there are things that I won’t do …. my limits, you know … as a midwife … or, uh … it doesn’t feel good, you know … personally that is a personal motive, and … I think, well … that’s how care is organized, that’s the system… I have to consider my own private life (…) I am not getting paid for that…”

Mostly all of the midwives perceived lack of time and the weight of their workload as the predominant extrinsic barriers for providing woman-centered care. Protocols and local regulations about coordination and cooperation of care were also perceived as extrinsic barriers, although at the same time the lackof a code of ethics and guidelines about woman-centered care were also mentioned as barriers. Additionally the woman herself and her unrealistic, or sometimes even unsafe, wishes and expectations were perceived as extrinsic barriers. Wishes of women that were out with national guidelines, such as the wish to give birth unattended, were frequently mentioned as extrinsic barriers for woman-centeredness.

“When you think or feel that you are unable to assess the mother’s or baby’s condition because of something she [woman] wants … how can that be woman-centered … when I am concerned about complications or growth … and she doesn’t want to be referred (…) that’s not woman-centered, that is being hindered.”

Supporting factors

Some midwives perceived that being familiar with the characteristics and the health needs of their population positively contributed to their woman-centered care approach. The more at ease they were with their own clientele the more able they were to be woman-centered. Being knowledgeable about the elements of woman-centered care but also knowledge of human nature was regarded as helpful to provide woman-centered care. Besides humanitarian knowledge about their own clientele, several midwives mentioned that seamless multidisciplinary care contributes to woman-centered care. Furthermore, most midwives experienced that the size of their practice or team played a role in woman-centered care. Small-sized practices were perceived as having a positive influence. However, larger teams could be supportive but only if colleagues’ had similar views, beliefs and attitudes about woman-centeredness.

“We have a small-sized practice, thus we work with two midwives and do everything ourselves, uh, that is not really woman-centered as well as … uh … yes, well both of us [midwives in the practice] think continuity makes our care woman-centered (…) we both [midwives in the practice] feel exactly the same about it [continuity of care] and think continuity is important.”

Some midwives remarked that care models such as centering pregnancy or caseload midwifery as well as the use of birth plans are contributing factors to woman-centered care.

Midwives’ characteristics

In order to provide woman-centered care, in general midwives perceived that flexibility, total and full commitment, genuine interest in others, generosity, empathy, being a good communicator and being sensitive and understanding, being non-judgmental, unprejudiced and unassuming, are all required characteristics for midwives to fully provide woman-centered care. They identified these characteristics as altruistic and vocational and these were likely to influence self-efficacy but also beliefs about themselves.

“To provide woman-centered care you have to be like, yeah, well, mother Theresa, and that’s not me.”

Personal factors

Midwives who were mothers perceived that their attitude about woman-centered care was influenced by their own experiences with pregnancy, childbirth and motherhood, and their own personal experiences with maternity care and maternity healthcare providers. Most midwives also regarded that their own outlook on life, religion and moral, influenced their realization and interpretation of woman-centered care because their own view and meaning play a role in the care they provide.

“Personally I would find it really distressing to support women, in a woman-centered way, after an abortion, for instance …. than … well … you have to … well you have to ‘press a switch’ so to speak … yes…”

Discussion

In this study we explored the underlying self-perceived attitudes, social influence, self-efficacy, intentions, barriers, characteristics and personal barriers of Dutch midwives’ woman-centered care behaviour. Perceived barriers but also supporting factors, including social influence and personal factors seemed to have a profound effect on midwives’ woman-centered care provision but also affected midwives’ attitude about this philosophy of care and their intention to provide woman-centered care. Additionally attitude was influenced by midwives’ characteristics and personal factors and self-efficacy was influenced by perceived mandatory characteristics of midwives and lack of guidance.

Midwives described several elements of midwifery care, such as needs assessment, information provision and continuity of care, which midwives considered to agree with woman-centered care. The overall attitude among midwives about woman-centered care was positive and woman-centered care was perceived as care that is adapted to women’s needs but it wasn’t regarded as inexhaustible or absolute. The emphasis seemed to be on the limitations and not on the positive elements, thoughts or consequences of woman-centered care. All midwives said to be willing to provide woman-centered care. However, when midwives voiced their intention they also related this to reasons why in practice it wasn’t achievable to provide woman-centered care. Our findings showed a paradox between midwives’ intentions, attitude and actual provision of woman-centered care.

The perceived incapacity to provide woman-centered care was accompanied by the description of a set of very high standards or moral characteristics required for woman-centeredness. Midwives described characteristics, such as commitment and generosity, which they perceived as conditional to provide woman-centered care. Interestingly, these characteristics were quite vocational and altruistic. Studies have indeed shown that the meaning of being a midwife is more than ‘just a job’ because it entails commitment to oneself [37-39]. Together, this implies that midwives set high standards for themselves bordering on perfection and excellence and relate this to their personal identity [38]. Our study as well as others demonstrated that by doing this midwives subsequently create an image of a midwife who is out-of-reach and maybe even unrealistic. It is known that when an ideal is not achievable and when midwives perceive this as a result of lack of time or when there is no relevant code of ethics or no guidance,midwives create alternative adapting strategies in their care provision [40]. This seems congruent with the findings of our study.

Next to the fact that the above suggests that midwives might have created obstacles that prevent them to provide woman-centered care, they also experienced barriers. A lack of time was mentioned as a barrier for woman-centered care behaviour. Interestingly, time is often mentioned as a barrier in midwifery care provision [41-43]. It would be of worth to explore if woman-centered care does require more time than usual midwifery practice. An additional explanation of creating barriers to provide woman-centered care is the interest of midwives in this philosophy of care [10,15]. Interest is regarded to be vital for engagement in clinical practice [42] and is also known to be a predictor for the intention to provide care, long-term involvement and professional commitment [44]. It might be of worth to investigate this in future research.

The lack of knowledge about woman-centered care and lack of an ethical code and guidance affected midwives’ self-efficacy of providing woman-centered care. It is known that self-efficacy influences attitude and intention [44]. Self-efficacy in our study seemed to be mostly influenced by barriers. Interestingly, midwives’ barriers were predominantly identified in relational aspects with women or colleagues. Professional socialisation of midwives has been recognized to play a role in adopting a philosophy of care like woman-centered care and influences attitude, attention and self-efficacy [22,45,46], which seems consistent with our findings.

Midwives in our study said that being a mother influenced their woman-centered care behavior, although they didn’t elaborate on the topic. Personal experiences, positive or negative, with maternity care can contribute to the midwife’s attitude, beliefs and intention to provide woman-centered care. Positive experiences lead to the desire to offer the same positive experience to others and a negative experience leads to the aim to give other women a better and satisfying experience [46,47]. These intentions are related to deep-rooted ideology [46]. However, being a midwife or being a mother are both associated with a huge sense of commitment. Both roles entail important core values, and it has been reported that fulfilling these roles simultaneously to one’s best abilities, is too challenging and too ambiguous [48].

Our findings showed that women substantially direct how woman-centered the midwife practises. Women may not be regarded as the leader of their care [49] however a relationship based on equity is at the heart of the woman-centered care philosophy [50]. The fact that Dutch midwives are autonomous and independent practitioners [51] might influence this perception and make them more midwife-centered, where the midwife directs the care model and the content of care [37]. In our study midwives also mentioned that being familiar with the women in their practice facilitated woman-centered care. However, most Dutch midwives practise in larger-sized practices [2] and this number is still increasing, similar to the increasing number of midwives that work in clinical settings [2]. The turn to larger group practices alters the relationship between the midwife and the woman. In solo-practices women are more able to develop a relationship with their midwife compared to larger-sized practices [51,52]. In our study it showed that midwives are more inclined to provide woman-centered care to assertive women. The art of midwifery, however, is to provide the same care to all women, regardless the level of women’s assertiveness or characteristics.

Additionally, several times midwives expressed that guidance about woman-centered care were needed to provide concurrent care. Understanding the midwifery care philosophy helps to practice according to this philosophy and increases self-efficacy [22], thus a philosophical underpinning seems imperative [50]. Further exploration of the concept of woman-centered midwifery care is crucial, leading to a clear definition and understanding, and contributing to a code of conduct of woman-centered care. In addition to this, midwives and student midwives should be facilitated to explore their own belief systems and constructs of woman-centered care critically so that they are better equipped to provide woman-centered care, regardless the setting they work in [46].

Despite the small number of participants in this study, the findings expand our knowledge and understanding of the underlying factors that affect woman-centered care of Dutch midwives. We did not reach saturation, however, we did not intend to reach this as congruent with our chosen methodology for the study [29,33]. Our purposive seIection method may have introduced selection bias and we may have included midwives with a positive attitude about woman-centered care. Moreover, only 19 midwifery practices voiced their vision about woman-centered care. This makes it likely to assume that woman-centered care is either not regarded as standard care, or being accepted as standard care provision or as core midwifery practice. It also might be worth considering if the questions in the interviews about midwives’ intentions have induced socially desirable answers although the researchers were unfamiliar with the participants, which is unlikely to have influenced the truthfulness of their answers. The underlying factors of midwives’ woman-centered behaviour were a prioristructured on the ASE model and we expanded the existing model. The ASE model in itself is able to explain behaviour but relevant expansion of the model allows an even better understanding of the behaviour[53]. The strengths of this study are that an in-depth analysis of midwives’ perceptions regarding the topic has identified aspects of midwives’ behaviour which are congruent with international literature but at the same time are very specific for Dutch midwives within the obstetric care system. The findings can be used to raise awareness about behavioural processes and to provide guidance on ensuring arrangements to embed the key point of the report ‘A good start’ into midwifery practice and into education of (future) midwives.

Conclusion

Our research identified the underlying factors that affect midwives’ woman-centered care but also acknowledged a paradox between behaviour and the underlying behaviour determinants, specifically attitude and intention. The findings of our study lead to believe that therefore Dutch midwifery needs a framework and guidance consistent with the philosophy of woman-centered care in order that (student) midwives are able to offer concurrent care to women.

References

- CVZ (2003) Verloskundig Vademecum [Obstetric Manual]. Diemen: College voor Zorgverzekeringen.

- Hassel DTP, Kasteleijn A, Kenens RJ (2015) Cijfers uit de registratie van verloskundigen [Registration figures midwives]. Utrecht: NIVEL.

- Reitsma E, Groenen C, Fermie M (2007) Takenpakket Eerstelijns Verloskunde 2007 [Midwifery in the Netherlands]. Utrecht: Koninklijke Nederlandse Organisatie van Verloskundigen.

- de Boer J, Zeeman K, Offerhaus P (2008) KNOV-Standaard prenatale verloskundige begeleiding, wetenschappelijke onderbouwing [Guideline prenatal midwifery care]. Utrecht: KNOV.

- Perinatale Zorg in Nederland 2013 [Perinatal care in the Netherlands 2013]. Utrecht: Stichting Perinatale Registratie Nederland, 2014

- Zeitlin J, Wildman K, Bréart G, Alexander S, Barros H, et al. (2003) PERISTAT: indicators for monitoring and evaluating perinatal health in Europe. Eur J Public Health 13: 29-37. [Crossref]

- Peristat II: EURO-PERISTAT project in collaboration with SCPE, EUROCAT and EURONEONET. European perinatal health report. Better statistics for better health for pregnant women and their babies in 2004. 2008 Available: www.europeristat.com

- Stuurgroep zwangerschap en geboorte (2009) Een goed begin, Adviesrapport. [Dutch Steering Committee Pregnancy and Birth. A Good Beginning, Advisory Report]. The Hague: VWS.

- Health Care Inspectorate (2014) Mogelijkheden voor verbetering geboortezorg nog onvolledig benut. Samenvattend eindrapport van het inspectieonderzoek naar de invoering van het Advies van de Stuurgroep Zwangerschap en Geboorte [Possibilities for improvement perinatal care insufficiently employed]. Den Haag: Inspectie voor Gezondheidszorg.

- ICM (2011) International Confederation of Midwives. The philosophy and model of midwifery care. The Philosophy and Model of Midwifery Care. Available at: http://www.internationalmidwives.org/2012/04/22/

- Leap N, Pairman S. Working in Partnership (2010) In Pairman S, Tracy SK, Thorogood C, Pincombe J (2nd Ed.), Midwifery: Preparation for Practice. Chatswood, NSW: Elsevier.

- Dahlberg U, Aune I (2013) The woman’s birth experience – the effect of interpersonal relationships and continuity of care. Midwifery 29: 407-415. [Crossref]

- Sandall J, Soltani H, Gates S, Shennan A, Devane D (2013) Midwife-led continuity models versus other models of care for childbearing women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

- McLachlan HL, Forster DA, Davey M-A, Farrell T, Flood M, et al. (2015) The effect of primary midwife-led care on women’s experience of childbirth. BJOG 123: 465-474. [Crossref]

- MHMRC (2010) National Health and Medical Research Council. National guidance on collaborative maternity care. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council.

- Epstein RM, Street RL (2011) The values and value of patient-centered care. Ann Fam Med 9:100-103. [Crossref]

- Lee Davis D, Walker K (2011) Case-loading midwifery in New Zealand: bridging the normal/abnormal divide ‘with woman’. Midwifery 27: 46-50. [Crossref]

- Morgan SS, Yoder L (2011) A concept analysis of person-centered care. J Holist Nurs 30: 6-15. [Crossref]

- Berg M, Asta Ólafsdóttir O, Lundgren I (2012) A midwifery model of woman-centered childbirth care-in Swedish and Icelandic settings. Sex Reprod Healthc 3:79-87. [Crossref]

- Maputle MS, Donavon H (2013) Woman-centered care in childbirth: A concept analysis (Part 1). Curationis 36: E1-E8. [Crossref]

- Van Kelst L, Spitz B, Sermeus W, Thomson A (2013) A hermeneutic phenomenological study of Belgian midwives' views on ideal and actual maternity care. Midwifery 9-17

- Yanti Y, Claramita M, Emilia O, Hakimi M (2015) Students’ understanding of “Women-Centered Care Philosophy” in midwifery care through Continuity of Care (CoC) learning model: a quasi-experimental study. BMC Nurs 14: 22. [Crossref]

- Armitage CJ, Conner M (2001) Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behaviour: a meta-analytic review. Br J Soc Psychol 40: 471-499. [Crossref]

- Creswell JW (2007) Qualitative inquiry and research design. Choosing among five approaches (2nd Ed.). Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

- Flick E (2002) An introduction to qualitative research (2nd ed.) London: Sage Publications.

- Townsend E, Langille L, Ripley D (2003) Professional tension in client-centered practice: Using institutional ethnography to generate understanding and transformation. Am J Occup Ther 57: 17-28. [Crossref]

- Edson Escalas J (2007) Self-Referencing and Persuasion: Narrative Transportation versus Analytical Elaboration. Journal of Consumer Research 4: 421-429

- Fina A, Perrino S (2011) Introduction: Interviews vs. ‘natural’ contexts: A false dilemma. Language in Society. 40: 1-11

- Watts S, Stenner P (2012) Doing methodological research. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Sandelowski M (2000) Combining qualitative and quantitative sampling, data collection, and analysis techniques in mixed-method studies. Res Nurs Health 23: 246-255. [Crossref]

- Boeije H. Analyseren in kwalitatief onderzoek [Analysing qualitative research]. Den Haag: Boom Lemma; 2012

- CCMO. Central committee on research involving human subjects. 2014. Available

at: http://www.ccmo.nl/en/your-research-does-it-fall-under-the-wmo.

- Kampen JK, Tamás P (2014) Overly ambitious: contributions and current status of Q methodology. Qual Quant 48: 3109-3126.

- Cesario S, Morin K, Santa-Donato A (2002) Evaluating the level of evidence of qualitative research. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 31: 708-714. [Crossref]

- de Vries H, Mudde AN, Dijkstra A (2000) The attitude-social influence-efficacy model applied to the prediction of motivational transitions in the process of smoking cessation. In P. Norman, C. Abraham, & M. Conner (Eds.) Understanding and changing health behaviour: From health beliefs to self-regulation. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic.

- de Vries H (1993) Determinanten van gedrag. In V. Damoiseaux, H. v. Molen, & G. Kok, Gezondheidsvoorlichting en gedragsverandering. Assen: Gorcum & Comp B.V.

- Fontein Y (2007) Making the transition from ‘being deliverd’ to ‘giving birth’. Midwifery Digest 17: 35-40.

- Hall J (2012) The Essence of the Art of a Midwife: Holistic, Multidimensional Meanings and Experiences Explored Through Creative Inquiry. PhD; University of the West of England.

- Gilkison A, McAra-Couper J, Gunn J, Crowther S, Hunter M, et al. (2015) Midwifery practice arrangements which sustain caseloading Lead Maternity Carer midwives in New Zealand. New Zealand College of Midwives Journal. 51:11-16.

- Lipsky M (1980) Street-level bureaucracy: Dilemma’s of the individual in public services. New York: Russel Sage Foundation.

- Price JH, Jordan TR, Dake JA (2006) Perceptions and use of smoking cessation in nurse-midwfe’s practice. J Midwifery Womens Health 51: 208-215. [Crossref]

- Fontein-Kuipers Y, Budé L, Ausems M, de Vries R, Nieuwenhuijze M (2014) Dutch midwives’ behavioural intentions of antenatal management of maternal distress and factors influencing these intentions: An exploratory survey. Midwifery 30: 234-241. [Crossref]

- Merkx A, Ausems A, Budé L, de Vries R, Niewenhuijze M (2015) Dutch midwives’ behaviour and determinants in promoting healthy gestational weight gain, phase 1: A qualitative approach. International Journal of Childbirth 5:126-138.

- Silva PJ. Exploring the psychology of interest. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006

- Parsons M, Griffiths R (2007) The effect of professional socialization on midwives’practice. Women and Birth 20: 31-34. [Crossref]

- Fraser D, Hughes A (2009) Perceptions of motherhood: the effect of experience and knowledge on midwifery students. Midwifery 25: 307-316. [Crossref]

- Hunter B (2008) A hermeneutic phenomenological analysis of midwives’ ways of knowing during childbirth. Midwifery 24: 405-415. [Crossref]

- Fenwick J (1998) Mothering and midwifery: sometimes a challenge. Aust Coll Midwives Inc J 11: 13-18. [Crossref]

- Chief Nursing Officers of England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. Midwifery 2020. Delivering expectations. Cambridge: Jill Rodgers Associates; 2010.

- Pairman S, Tracy S, Thorogood C, Pincombe J (2010) Midwifery. Preparation for practice (2nd Ed.). Chatswood: Churchill Livingstone.

- de Vries R, Nieuwenhuijze M, Buitendijk SE (2013) What does it take to have a strong and independent profession of midwifery? Lessons learned from the Netherlands. Midwifery 29: 1122-1128. [Crossref]

- Fontein J (2010) The comparison of birth outcomes and birth experiences of low-risk women in different sized midwifery practices in the Netherlands. Women and Birth 23: 103-110. [Crossref]

- Eccles MP, Grimshaw JM, McLennan G, Bonetti D, Glidewell L, et al. (2012) Explaining clinical behaviour using multiple theoretical models. Implement Sci 7: 99. [Crossref]